A detailed review by Martin van der Ven (March 2025)

Radio stations on ships in international waters (often incorrectly called pirate stations) have been associated for decades with radio stations in the North Sea that broadcast pop and rock music, such as Radio Caroline or Radio Veronica. Accordingly, countless publications deal with the well-known phenomenon. But in 1993 Radio Brod (“Radio Boat” in Croatian) emerged. In the middle of the worst armed conflict in Europe since the Second World War, a completely different radio station appeared off the coast of the former Yugoslavia, primarily transmitting messages of peace and understanding from the ship Droit de Parole (Freedom of Speech) throughout the war-torn region. It was a station that has unfortunately been forgotten in 2025, and its importance cannot be overestimated even three decades later.

![]() Nederlandstalige versie –

Nederlandstalige versie – ![]() Deutschsprachige Version

Deutschsprachige Version

The Political Background

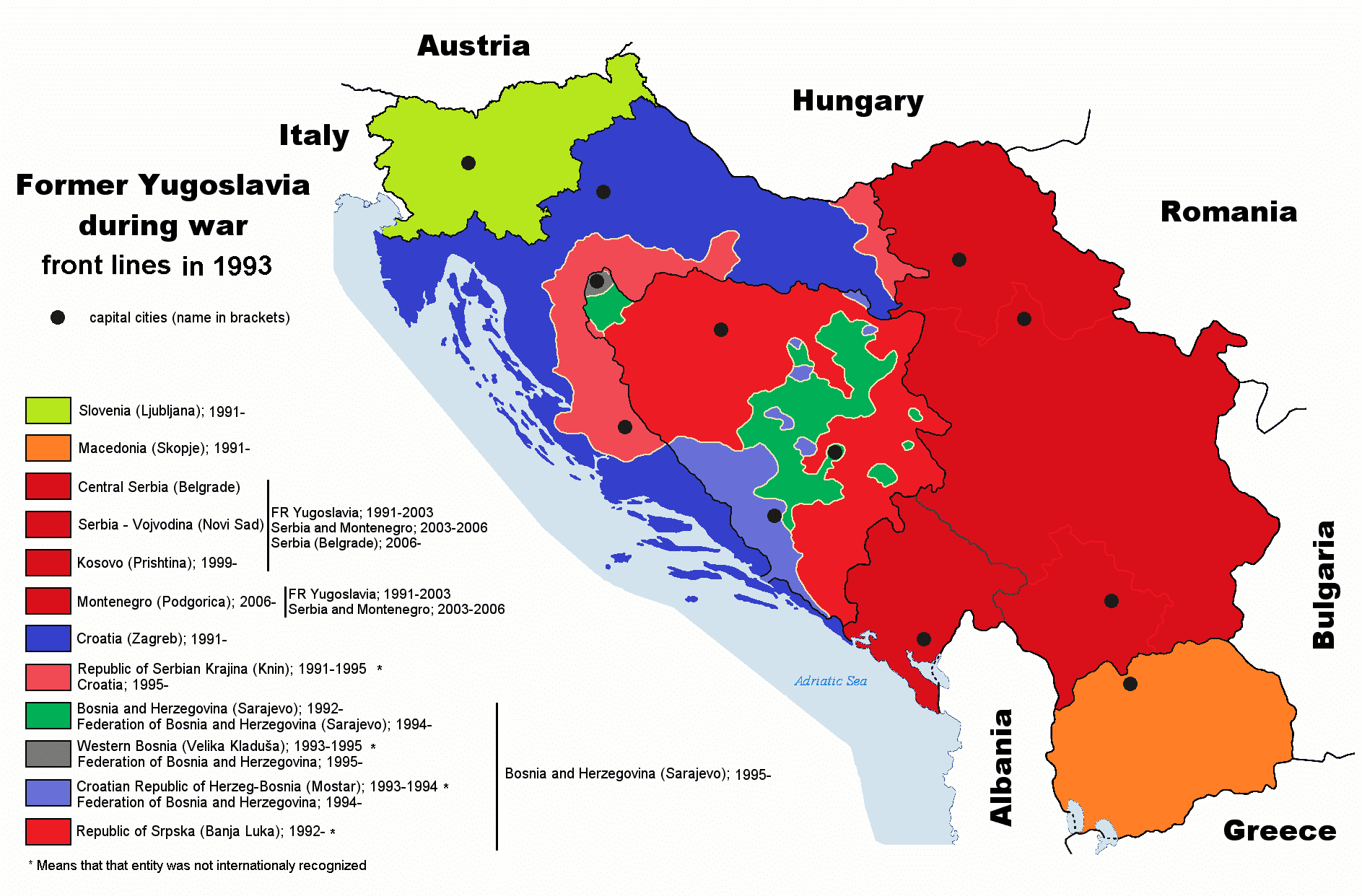

After the fall of the Berlin Wall, the “Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia” (SFRY) broke apart into its six constituent republics in 1991: Serbia, Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Macedonia, Slovenia and Montenegro. Within each of these, individual religious and ethnic groups were claiming larger shares of territory and political dominance. This led to a civil war, often referred to as the Balkan War, which lasted a decade. Long-suppressed national and religious identities collided. Conflicts between Serbs (predominantly Orthodox), Croats (predominantly Catholic) and Bosniaks (predominantly Muslim) escalated into violent clashes in which ethnic cleansing, systematic expulsions and massive human rights violations were the order of the day. Entire population groups suffered from the loss of home, identity and trust. Plagued by hunger, cold and fear, the people in cellars and ruins once again experienced a bitter winter of war.

Countless ceasefire negotiations failed, and almost all major cities and towns in Serbia, Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina were destroyed by ground fighting and air strikes. Huge numbers of people in the region were killed or left homeless.

Residents of different ethnic groups increasingly found themselves caught up in the maelstrom of nationalist violence and disinformation during the armed conflicts. Communication infrastructure, essential for a healthy cultural life, almost completely collapsed. The only independent and unfiltered sources of information that could be considered were the foreign radio stations Voice of America, BBC, Deutsche Welle and Radio France Internationale, which broadcast programmes in the Serbo-Croatian language.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Map_of_war_in_Yugoslavia,_1993.png

English Wikipedia user swPawel, CC BY-SA 3.0 <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/>, via Wikimedia Commons

The Idea and the Sponsors

More and more Yugoslavian journalists suffered from a repressive working climate in their homeland and emigrated to Paris. Among them was the former Montenegrin newspaper editor

Dragica Ponorac, who previously worked at the independent Montenegrin weekly magazine Monitor. The journalists together wanted to send objective news to the former Yugoslavia to end the paranoia fuelled by propaganda and misinformation. The plans were also inspired by an earlier sea broadcasting project: political radio broadcasts for China were to begin in the spring of 1990 from the ship “Déesse de la Démocratie”. The early failure of this ambitious project did not discourage those who came up with the ideas. A suitable transmitting ship was soon sought. A station based in Hungary was initially considered, but that plan was quickly abandoned because of the fear of sabotage. Also, Radio Caroline’s broadcasting ship ‘Ross Revenge’ was considered, but the British Department of Transport would not give their approval. At the end of February 1993, French newspaper reports mentioned for the first time a new broadcasting ship ‘Droit de Parole’, which had been chartered by a non-commercial organisation of the same name, and which was being equipped in Marseille.

The organisation had been founded in Paris in August 1992 by the Polish civil rights activist and politician Tadeusz Mazowiecki. As a United Nations special rapporteur on human rights, he advocated for the idea of establishing an independent floating radio station for the disintegrating Yugoslavia. He said there must urgently be free information and a “containment of incitement to hatred”. Accordingly, he called for the “right to media intervention” in the former Yugoslavia.

The proponents of the project also included personalities such as Susan Sonntag, Tilt Mafuhz and Elie Wiesel.

- Danielle Mitterand’s foundation, France Libertées,

- the general director of UNESCO, Federico Mayor Zaragoza,

- an anonymous British organisation, and

- various press groups in the USA, including the Washington Post, New York Times and the PEN American Centre (pen.org).

Originally, at the beginning of 1993, funding was also promised from the then French Minister for Health and Humanitarian Aid, Bernard Kouchner. However, after the French parliamentary elections in March 1993 and the associated change of government, this offer was withdrawn. The new government took the view that the offshore radio project violated international regulations and conventions.

The Radio Ship

The Fort Reliance was built in 1985 by Appledore Ferguson Shipbuilders Ltd in the port of Glasgow as a supply ship. In 1989, she was converted into a polar ship by “San Giorgio del Porto” in Genoa, Italy. The ship was ice-reinforced and equipped with fire-fighting equipment for Antarctic survey work. In the same year the Fort Reliance was renamed Cariboo.

For the Radio Brod project, the ship was converted into a radio ship at Quay 114 of the Bassin d’Arenc in Marseille and then chartered by the Compagnie Nationale de Navigation (CNN) for £7,000 per day. A 28 meter high antenna mast was installed. It resembled a small Eiffel Tower and stood on a white container with portholes.

The ship was then renamed Droit de Parole. The independent, non-commercial Paris-based non-governmental organisation of the same name, founded in August 1992, sub-chartered the radio ship. Her official address was a PO Box (BP 6, 75922 Paris Cedex 19). The daily rent of the ship and crew was 55,500 French francs.

The first security measures began when the Droit de Parole was still in the port of Marseille and was converted into a broadcasting ship. A former combat diver repeatedly checked whether explosives had been attached to the hull of the ship, as had once been the case on the Greenpeace ship “Rainbow Warrior”.

Technical data:

Total length: 65.36 m

Width: 12.80 m

Height: 5.35 m

Gross tonnage: 1597 Tx

2 “MIRRLEES” engines with 3083 BHP each

Total power: 6166 BHP at 1000 rpm

2 propeller shafts, 2 variable pitch propellers

1 bow thruster with 500 BHP, thrust 5.5 T

3 generators with 300 kW each, driven by 3 diesel engines with 300 kW each at 1800 rpm

Consumption 20 m³/day at a maximum speed of 14 knots

Consumption 12.3 m³/day at an economic speed of 12 knots

Range: 10,550 nautical miles at 12 knots

Deck Load: 500 T

Deck Strength: 5 T/m²

Load capacity: 950 T

Fuel: 495 m³

Drinking water: 300 T

Ballast Water: 530 T

2 closed “WATERCRAFT” type lifeboats for 32 people each

4 life rafts for 25 people + 2 for 12 people each

2 anchors + 1 spare anchor each 1140 kg

63 berths

2 mess rooms with television

1 lounge + 1 meeting room

Fully air-conditioned accommodations

Helipad for Alouette, Lama or Ecureuil

The French Foreign Ministry refused permission to fly the French flag. The security of the French peacekeepers was given as an excuse. The Droit de Parole was then registered in Kingstown, the capital of the island state of St. Vincent and the Grenadines. A rumour that the ship might sail under the flag of Kerguelen (in the French Antarctic), did not come true.

Supplies were tendered out from Bari, Italy, often using the motorboat “Hamra”. There was also an office address in Bari: Via Dante 46 LA, Bari 70123.

Here is a recording of the radio traffic with the ‘Hamra’:

After the project ended in March 1994, the ship was returned to Marseille where all broadcast equipment was removed. She was then returned to her original owners.

In the same year, the Droit de Parole was purchased by the Veesea company and renamed Veesea Pearl. Under this name she served as a security standby ship in the North Sea oil industry. In 2000 she was sold to Seahorse in Ireland and given the name Pearl. In 2016, the ship was once again renamed KARADENIZ POWERSHIP REMZI BEY and began sailing under the Liberian flag, but she has been out of service since 2020.

The Technical Equipment

The Droit de Parole had a 50 kW medium wave transmitter donated to the project by Telediffusion France (TDF) and previously used by Sud Radio in Andorra. It broadcast on 720 kHz (417 m). A 10 kW FM transmitter was deployed on 97.8 MHz. The antenna was an end-fed type attached to the top of the A-shaped mast.

Radio Brod set sail from Marseille on March 31, 1993. Test broadcasts began on April 7, 1993 at 11:00 p.m.

Initially there was interference from the ship’s on-board radio, so the Droit de Parole had to return to port after a few days to resolve the problem. At the same time, storm damage to the ship was repaired. On April 17, 1993, the ship went out to sea again and broadcasts from Radio Brod resumed shortly afterwards. The official broadcasts – from then on around the clock – began on June 1, 1993.

Two studios were built on board the Droit de Parole – a broadcast studio and a production studio – as well as two editing rooms. The journalists communicated with their contacts in the former Yugoslavia and other countries via an Inmarsat satellite system as well as marine radio, cell phones and a direct radio link.

The Droit de Parole had:

4 portable VHF radios “ICOM IC MSF”

1 SATNAV ”MAGNAVOX MX 4102“

1 GPS ”Raystar 590“

2 radar devices 3 cm ”DECCA RM 1216 G“

1 shortwave radio telephone ”SAILOR 800 W Type T 1127“

1 shortwave radio telephone ”SAILOR 400 W”

1 satellite communication system (INMARSAT)

1 phone/Telex/Telefax ”J.R.C JUE 45 A“

1 fax receiver for weather maps ”KODEN Fx7181”

Because of the high voltage on the long-span antenna wires, short circuits could occur. The cables that led from the transmitter to the transmission tower were exposed. This caused a great deal of RF energy (‘electrosmog’) on board.

The field strength of the 50 kilowatt medium wave transmitter was so strong that it penetrated devices the broadcasters had brought with them. Camera crews filming on board also had this problem. Their cameras had to be wrapped in aluminium foil, to block out radiation.

Every now and then there was lightning overhead, but there was no romantic storm. The editors were aware that the transmitter’s field strength could also lead to health problems and removed some dead birds on board.

Editor Maja Razovi said she hoped that they would at least be safe from radiation in the container.

Up to 20 people lived in close quarters and without much comfort. Anyone wanting to reach the canteen on the lowest platform had to squeeze past the machines in narrow corridors. Although the noise of the machines penetrated even through the thick steel doors, silence was requested because part of the ship’s crew slept between the canteen and the engine room. Steep stairs, more like metal ladders, led to the two upper floors. From the narrow corridors, which smelled of machine oil, the cabins of the radio staff and their guests branched off: a bunk bed, a desk, and a shower with a toilet in a 6-square-meter space. Even the radio studio, whose furnishings seemed very improvised, was only slightly larger. Without being separated by a glass pane, the programme was produced here by the presenters and two French technicians. The ship’s engines were unmistakably loud. In the adjacent telecommunications room, editors were cutting the reports from correspondents transmitted from the former Yugoslav mainland via satellite, mobile phone, or shortwave. One floor above was the largest room in the container, the editorial office. Here, texts were written, newspapers evaluated, and the daily editorial meeting held. The ship was a hive of activity. Hardly anyone would have guessed, upon seeing the radio team in jeans, T-shirts, and flip-flops, that they were journalists who had been well-known in their former homeland. The radio ship resembled a testing station, its creators adventurers. When considering the background of those involved, this image was not so far-fetched.

Here is a recording from the studio:

The Protagonists

The radio ship sometimes gave the impression of a 66 meter long and 13 meter wide Little Sarajevo in peacetime. The editorial team on board consisted of a multi-ethnic team of Croats, Serbs, Muslims, Slovenes, Montenegrins and Macedonians. In addition, there was its own, extensive network of independent, often anonymous or secret correspondents, which comprised around 50 employees and extended across all the former Yugoslav republics. Some of the correspondents reported at great risk to their lives. Using the satellite phone they were able to conduct interviews with people live on board. Their contributions were often chronicles of powerlessness, overlaid with metallic, withdrawing voices, interspersed with beeping tones broadcast by radio amateurs on the single-sideband (SSB) frequency. They reported on the atrocities in Gorazde, Vitez and Travnik in Bosnia, as well as skirmishes on the Dalmatian coast. These independent journalists took big risks. One of them was quicker than the news agencies: He was the first to report that the Bosnian government’s interior and defence ministers had just been replaced.

Listen to a live report by Mehmet Agović (Radio Brod correspondent in Sarajevo):

This network of correspondents in particular was unique and unparalleled by any land-based radio station: daily connections were made to Zagreb, Belgrade, Sarajevo, Mostar, Split and many other places. For the editors, the correspondent in the Bosnian Serb town of Banja Luka was considered the bravest of all – given the threatening atmosphere there and his critical attitude towards the local authorities.

The Montenegrin journalist Nebojša Redžić initially worked as a correspondent from Podgorica for Radio Brod, and later also aboard the Droit de Parole: “Some media outlets had ‘learned from reliable sources’ that such an ‘anti-Serb project’ was being prepared. At the same time, however, Croats regarded it as anti-Croatian and Bosniaks as anti-Muslim. So, I concluded, it had to be good. What was striking was that among all the media in the former Yugoslavia, the dirtiest and most deceitful articles were published in Pobjeda from Podgorica – in stark contrast to benevolent papers such as Vreme, Borba, or Monitor.

Under the title Waves of Misunderstanding – in a tone more fitting for Goebbels’ propaganda machine – Pobjeda also published the composition of our editorial team on 16 April 1993, in a context that sounded like a call to target us. They had no idea how pleased I was to find my own name in that article: ‘Editor-in-chief is Dževad Sabljaković. Other members of the editorial team include Maja Razović, Aleksandar Mlač, Rajko Cerović, Lazar Stojanović, Konstantin Jovanović, and Srđan Kusovac… Reporting from Podgorica is Nebojša Redžić; from Belgrade, Zoran Mamula; from Sarajevo, Zlatko Dizdarević; Zagreb correspondent is Jelena Lovrić; from Priština, Škeljzen Malići; from Ljubljana, Zaherijah Smajić; and from Split, Goran Vežić, Srđan Obradović and Zoran Daskalović.’”

Here is an example of radio communication with a correspondent:

The Radio Brod team included not only respected and well-known journalists from all warring regions of the former Yugoslavia – Roman Catholics, Orthodox Christians and Muslims. The captain, Thierry Lafabrie, and the radio technician Jean-Pierre Grimaldi both came from France. The mixed crew was made up of French and Indians.

What the employees from the former Yugoslavia had in common was that they had been laid off as radio specialists or could no longer stand it at their own station when the new totalitarian wind of local nationalism arose there in recent years. Individuals also had personal reasons for the rough life at sea, such as an employee whose boyfriend had been shot in Italy. Here on board, Yugoslavia still existed: the various dialects of what was once called Serbo-Croatian – now declared three separate languages on land (Croatian, Serbian and Bosnian) – were spoken fraternally to one another on the station.

However, the Yugoslavia on board the Droit de Parole was a minor-key Yugoslavia. “We sit here together for weeks,” said an editor from Croatia, while six coffee cups and other objects flew through the editorial room, which also served as a common room, in strong winds. “Everyone has a crisis from time to time, be it because of worries about their homeland or because of the general hopelessness of the situation.”

The war in the former Yugoslavia had left none of them unscathed, but the mood on board was mostly relaxed. A popular pastime was swimming with the mischievous dolphins that often appeared around the boat. They were the dearest company that warmed the hearts of these voluntary exiles.

Of course, life on board was no picnic. The journalists worked 16-hour shifts under the baking summer sun and the constant possibility of a torpedo attack. But the daring reporters refused to be intimidated. During their free hours, they sunbathed on the ship’s landing platform (known as “the beach”).

Afterwards, various Radio Brod employees had their say, some of whom were interviewed extensively in various newspapers, magazines and television reports in the period 1993-94. Below are some of those interviews.

Dževad Sabljaković worked at Radio Brod as editor-in-chief and coordinated both the internal resources and an extensive network of correspondents from the various regions of the former SFRY. Previously, from 1990 until the beginning of the war, he worked as editor-in-chief of the newly founded and first independent all-Yugoslav television station YUTEL. After it closed, he reported as a correspondent for RFI from war-torn Sarajevo. During his time at Radio Brod, he travelled around Europe to collect donations.

As in other Eastern Bloc countries, Yugoslavia’s communist regime left the nationalist governments of its successor states a media monopoly, which they used freely. Whether in the press, radio or television, the nationalist ideology of those in power found its way into almost all media. The newsrooms fell victim to what is widely referred to as “ethnic cleansing” and all those journalists and editors known for their objectivity and impartiality were fired in the name of the emergency and the state of war. The few independent media outlets that had formed at the local level were closed. Where they still exist, their work is hindered by intimidation and boycotts. Television, radio and newspapers became almost exclusively the mouthpiece of ultranationalist governments.

When he was editor-in-chief at Radio Brod, Sabljaković was in a unique position. There were countless unemployed journalists who refused to bow to pressure and refused to compromise on ethical principles. So he could draw on the best in his field and work with them on his ambitious 24-hour programme.

For him, the individual republics had long since transformed into hermetically sealed spaces: “Nobody in Zagreb knows what’s happening in Belgrade anymore,” he said in an interview. He compared the work of his editorial team to that of firefighters: “We want to put out the fire of hatred, we are not on any side. People have to talk to each other again and live together in peace.”

“We selected good journalists from all over Yugoslavia… We only took those who worked for the non-state-controlled press.” “There are only normal people on this ship – that makes us dissidents.” “We haven’t had a single argument so far,” said Sabljaković. “There are no nationalistic viewpoints here,” said the man in his fifties, explaining his recipe for success.

“All journalists here want democracy in all republics of the former Yugoslavia. Taking one side or the other would mean the continuation of the media war that existed before the war actually started. That’s why we try to be very distant, almost like strangers.” This also applies to the correspondents.

“Our correspondents,” he said, “have been selected not only on the basis of professionalism, but also because of their moral compass. Many of them previously worked in the official media and lost their jobs because of their critical attitude towards the nationalist governments.”

When asked whether there might be one or two national differences of opinion on board, there was thunder! Sabljaković’s Slavic bass voice said a decisive “No”. His people are characterized by the “power of distance,” he says. They are critical of their own governments. In addition, they would have the necessary self-assurance and professional integrity to resist petty nationalist banter.

The then 30-year-old Bosnian-Muslim editor Mirna Imamović was trapped in Sarajevo. She then managed to escape. On the radio ship she ran the programme “Desperately Seeking” with messages from refugees that were recorded in writing or orally on the spot. This meant that family and friends who lived in refugee camps across Europe and listened to the programme were able to find out about the whereabouts of their loved ones – sometimes even reuniting. Imamović said that the real significance of this opportunity was only understood when a thank you letter arrived. In it, a man from Trebinje in Bosnia-Herzegovina reported that thanks to Radio Brod he had found his orphaned grandchildren in a Danish refugee camp.

Looking back, Imamović recalled in an interview with the Italian broadcaster RAI that at that time, there were hardly any functioning telephone lines between the republics of the former Yugoslavia.

“From onboard, I had direct telephone contact with all the refugee camps. I read the refugees’ very personal letters on the radio in the hope that the intended recipients would also hear the messages. For many people, this was the only way to get in touch with each other, even to send a sign of life. Sometimes we all sat in the studio crying, because there were so many children who had not known for a year whether their parents were still alive.” “There were no ethnic tensions on board, only professional pride.”

Mirna Imamović found fulfilment in her job. Eight months after she left her home in Grbavica – the Serbian-held bulge that juts into the centre of Sarajevo – her mother, one of the few Muslims remaining there, turned on her transistor radio and listened to Radio Brod on 720 kHz. In the final seconds of “Desperately Seeking,” she heard her daughter’s name read in the credits as the producer.

“Refugee news was the most important thing we did,” said Mirna, who had been with the programme since it started. She spent her days calling refugee camps and recording voices. “It didn’t matter what the message said. It was just the voice that mattered. Can you imagine, after a year of not knowing whether your child or your wife was dead or alive, and then suddenly hearing their voice saying, ‘I’m fine. I’m here. I have enough to eat’? That was tangible.”

After learning that Mirna was still alive, her mother managed to get a letter to her – a Serbian friend took it to Belgrade, sent it to Mirna’s brother in Moscow, who then faxed it to the number listed in Radio Brod broadcasts. “If we managed to have a case every two months, then that was worth doing,” said Mirna. “I know this from personal experience. Until then, I didn’t even know if my own mother was still alive.”

Click on the following photos to enlarge them:

“If two or three of these calls per programme had any effect, I would be satisfied,” said the programme maker Konstantin Jovanović, a former editor of the television station TV Sarajevo, who himself came from Sarajevo and was involved in Radio Brod from its beginning in April 1993. He was a refugee himself, waiting for a visa to France with his wife and children in Croatia. “The most important thing is that this radio keeps broadcasting,” he murmured.

Jovanović was responsible for the programmes for refugees.

“All refugees are equal and belong to the same family,” he said. The journalists and editors shared the same problems as their listeners: lost homes, separation from families and the uncertainty of where they could return. “I assure you that the majority of people in Sarajevo and Bosnia believe that living together is necessary and possible. But they cannot say it openly. They are afraid.”

The then 37 year old Croatian Darko Rundek was one of the most famous musicians of the former Yugoslavia, a rock star and former director of Radio Zagreb. He also wondered how big his invisible audience actually was. Only later did he learn that people were gathering around their radios to listen to the programme together. “That’s what I remember most fondly,” he said, “we made our audience happy.” “This war was created by misinformation. We’re trying to put things in perspective so that maybe people can communicate with each other again.” “We have to look to the future, not back.”

“We have no political problems,” he said while sorting through the records for his farewell party after five months on board. “But we have problems that perhaps result from the fact that some people have certain national characteristics. This should not be seen as a continuation of the Yugoslav ideal. I am Croat and come from a family that has always seen itself as Croat.”

Dragica Ponorac, the former deputy director of the independent Montenegrin weekly magazine Monitor, had survived two bombings and eventually moved to Paris. There she became general secretary of the independent organisation “Droit de Parole”.

“This ship bothers everyone: freedom of expression is the biggest problem in Yugoslavia today.” “The UN convention was concluded by member states to take action against commercial radio stations broadcasting their programmes from international waters, but we have a humanitarian mission,” said the energetic daughter of a Serb and a Croatian. “We are fighting for the dignity of professional journalism, for an end to the war and the resumption of dialogue. For communication between the people and families the war has torn apart. All of this gives our project moral legitimacy.”

Humanitarian aid, she explained, does not just consist of food deliveries. Freedom of speech is also “a humanitarian necessity. That is why it is extremely important that we obtain the right to media interference through a UN resolution in cases where the problems are as serious as in the former Yugoslavia.”

The Croatian art historian Maja Razović lost her job twice in 1992. First she was fired for “subversive activity,” then her next employer, the weekly magazine “Novi Danas,” was brought to its knees by excessive printing costs and a distribution boycott. Nevertheless, she would have stayed in Zagreb.

“It’s just that I didn’t see any new projects emerging on the Croatian media horizon, and the offer to work on this radio ship was very interesting. That’s a challenge for any journalist.” What comes easily from her lips was difficult for her. She admitted that she was worried that she would end up on a Noah’s Ark where she would constantly be told that every Croatian was a member of the fascist and ultranationalist Ustasha organisation.

“One must not forget that from the summer of 1991 onwards, it was impossible to call Belgrade. There were no letters, no newspapers, no television, nothing. And then for two years there was just a sea of blood.” How did she lose her fear? “Metaphorically speaking, the decision to jump into the sea was enough.”

She experienced many surprises on board. For example, she wrote an angry comment when the Serbs destroyed a 16th century mosque in Banja Luca. The comment took the normal route across the desk of the editor on duty, who was a Serb that day. “Then this guy stood up and gave me a kiss, a Serb kissed a Croatian because she wrote something not very nice about the destruction of Muslim buildings.”

“I don’t think the channel will end the war, change professional norms or introduce a sudden respect for human rights,” she admitted. She compared the radio station’s function to the UN’s food drops over Bosnia. “Of course no normal person believes that this will feed every single hungry person. But symbolically speaking, this is very important because it shows these a**holes who don’t let the convoys pass that there are other ways.”

The then 49-year-old Serb Lazar Stojanović was a prominent journalist, anti-war activist and dissident in the former socialist Yugoslavia.

“We are not yearning for a new Yugoslavia; no one believes it is realistic to restore it. And every one of us, without exception, is aware of the weaknesses of the former Yugoslavia. So, if anyone accuses us of longing for the return of Yugoslavia, they are entirely mistaken.

We cracked thousands of jokes, but there wasn’t a single disagreement. The only clash I experienced was over a chessboard.

We highlight every abuse, every manipulation, and every persecution of minorities, regardless of who they are, what religion they follow, or to which ethnic group they belong. That’s why we encounter more rejection from the Serbs than from the Croats, even though we strive to be objective.

But I believe that, in time, as we develop stronger ties with the independent media in Serbia, this hostility will diminish. Moreover, my friend Srđan Kusovac from Radio B92 – the youngest star journalist from Belgrade – and I have never exactly been popular with the authorities or the nationalist opposition in Belgrade. Whenever we got near a microphone, they always sensed danger.

Not only the majority of Serbs but also some diplomats, both within and outside the European Community, would say – and this has become something of a trend – that the premature recognition of Croatia, Slovenia, and Bosnia led to the war. I believe the opposite. I think it was, in fact, the delayed recognition that encouraged the federal army and the Serbs to act as they did. Furthermore, it is not enough to recognise someone formally. The recognised must also be protected. And Europe was never sufficiently united or willing to intervene. On the other hand, it was also unwilling to leave the matter to the USA. So the recognition was not accompanied by military support, which opened the door to continued attacks and civil war in Bosnia.

In a situation like that in Bosnia – and in all places experiencing civil wars of a similar scale – no one can simply leave the area as they please, whether they are Bosniak, Serb, or Croat. And if you cannot leave, you cannot speak freely, you cannot oppose the dominant government ideology.”

Lazar Stojanović later recalled: “We met in Paris in April 1993: five journalists, three assistants and two music editors (Darko Rundek and Vedran Peternel) were preparing to embark. It was an attempt – both collectively and individually on the part of each of us – to use our resources to respond to the war in our homeland.”

Mirjana Dizdarević, a translator and music editor on board, had left everything behind in Sarajevo. She previously hosted a classical music show on Radio Sarajevo and now continued to do so three times a week on Droit de Parole. She emphasized: “Yugoslavia no longer exists, but we will still have to live with each other.” Music knows neither nationalism nor borders, but speaks a universal language and can therefore only unite.

Petar Savić, a then 25-year-old sound engineer who used to work at Radio B92 in Belgrade had just received his draft notice in Serbia.

Svetlana Vuković was tasked with sending reports from Belgrade on the contents of the Serbian weekly press.

43 year old Serbian Jasmina Teodosijević was a respected former foreign editor of the Belgrade daily newspaper Fight. Most of the channel’s crew agreed with Teodosijević’s assertion that “there is much less hatred, anger and resentment in the former Yugoslavia than one might imagine.” And it was their job to prove this. “Hopefully we will be able to eliminate the information chaos. Because in addition to the real war, we also have an information war. We are fighting against the propaganda war. As journalists, our job is to inform people.” “It can get very claustrophobic [on board]. All it takes is for one person to be aggressive and a chain reaction sets in.”

“The first and only purpose of the rotating 15-member team on Radio Brod (seven journalists, two sound engineers, two translators, two producers and two music editors from Sarajevo, Belgrade, Zagreb, Podgorica, Split, and Ljubljana) is to do their work honestly and produce the best programme possible. Is that even possible – from nothing, from the marine cosmos, while cruising or gently drifting between Bari and Lastovo (unless, as happened once, a storm pushes you all the way to Montenegro, where you can see Mljet, Korčula, Lastovo, the white speck of Dubrovnik and the Montenegrin mountains through the clear air)?

Amazingly, yes – because you don’t anchor. The anchor only reaches 20 metres, but here it’s about a kilometre deep. You’re aware of that – when swimming and when working. You rely solely on your own judgement. And of course, on the vast network of people on land who help create this programme – brilliant correspondents from Sarajevo, Podgorica, Split, Belgrade, Ljubljana, Skopje, Zagreb, Washington, Brussels, Geneva – among whom I must especially mention the always energetic, tireless Jelena Lovrić. And friends, colleagues, all those from whom reliable information and words can be obtained. Alongside news agency reports, listening to other radio stations, and any other available method to gather news.”

“I mostly learned what was happening through the local media, but that was biased and unreliable. After ten days I was supposed to send a report to Paris. Before I made the phone call, I re-read my report.” Peternel was astonished by it, and frankly confessed: “I wondered what I had written. Even I, living in France and only staying in Croatia for 14 days, was infected by this propaganda and disinformation. So you can imagine what the media does to people who are constantly exposed to it.”

Serbian journalist Srđan Kusovac also had a thing or two to say about this type of media landscape. Before he was hired as an editor for the radio ship, he worked as a presenter for the independent Belgrade local radio station “B92”. In his opinion, the war in the former Yugoslavia could only be ended through democratization, and he saw promoting this as his job as a journalist.

“You have to give people the opportunity to hear another side so that no one can exploit them for the sake of politics. We don’t claim to be the only ones who know the truth, but we simply want to give unbiased information.”

“If the warlords came here, they would learn tolerance,” he joked.

Srđan Karanović, a well-known film director from Belgrade, wanted one day to make a film about the disasters that struck his country – but only if he could use “a crew from all parts of Yugoslavia.”

If an unknown ship appeared on the radar screen after dark, the head of operations, Pierre Vierl, immediately called for the portholes to be darkened and all unnecessary lights to be extinguished.

“Everything is strange here,” he said in a calm voice, “and as soon as an unknown ship appears near us, whether it’s a cargo ship or a fishing boat, then we have to be careful about what it really could be. But apart from one threat, (when a man talking to the radio people said that he had heard something) “We haven’t had any real problems so far when it comes to getting on the ship.”

“Doing the right thing” – that was the goal of the entire crew. But maintaining moral principles in wartime means taking a stand and making yourself vulnerable. That’s exactly why Svetlana Lukić lost her position as a correspondent for Serbian radio and television: her reporting on the war against Croatia was too independent and did not fit the official line. She thought back wistfully about this time and saw it as a symbol of personal and generational failure. They wanted to stop the violence and provide counter-information, but that was ‘tilting against windmills’: the pacifists lost, “the nationalists won and destroyed the country, they are directly responsible for the war and are in power today.” This devalues everything that has been built up over thirty years of activism. Lukić came aboard the radio ship in autumn 1993 to spend the winter there. In early 1994, she jumped during the night and in stormy weather, wearing a life vest under floodlights, from the deck into a rubber boat, and from there into a speedboat, in order to work for Radio B92 in Belgrade.

Ines Sabalić, who came from Zagreb and worked for a publishing house in Split, had voluntarily resigned there: with the outbreak of war, the climate had changed; there was no longer any room for critical voices. “Journalism is not a mission, it’s a profession. So let’s stay professional,” she said. “This is a conscious decision – not a boat for a few eccentrics.”

Veselin Tomović was a journalist with Montenegrin Radio and Television (RTVCG). He left the broadcaster because his sensitivity did not align with the editorial line of the time. Nebojša Redžić wrote about him: “He is probably the best radio presenter in the history of Montenegrin journalism. His voice, his composure, his sense of humour, and even his irony during dark times – all of it consistently inspired me.” Tomović himself was critical of the frequent visits of international colleagues aboard: “That really drove you crazy. They interviewed everyone at least three times. And over and over again this question: ‘Why is there shooting at your home, what do you think?'”

“Between those who committed the crime of hiding behind nationalism and those who became victims of this war,” explains the essayist Rajko Cerović, who worked at Montenegrin television for 25 years, “journalism has proven to be the language of Aesop – the best and the worst at the same time, in the service of war or truth.”

Goran Vesić, who had come as reinforcement from Split, where he had founded a small news agency, confessed his “Yugo nostalgia” when speaking of this community on board – even though he knew the future would not allow for “Yugofuturists”.

“Technically, we’re a pirate radio station,” the captain Thierry Lafabrie admitted.” But the laws are inadequate. We are doing the right thing.”

“We have the kind of problems you have anywhere when a group of people are stuck on a boat just going in circles,” said Gilles, the (French) second engineer. “It’s difficult enough for us not to sail anywhere, but at least we’re used to the sea. For them [the journalists] it’s much worse. By the time we docked last Wednesday, we’d been at sea for 40 days. That’s a long time when you’re not used to it.” “There are personal problems here, not political ones – just the kind of problems you have everywhere when people live together in a small space.”

Political debates weren’t really in vogue on board – at most jokes during the many hours waiting for the next task. “It was still OK in the summer,” recounted an anonymous editor. “There we were, lying on our ‘beach,’ the aft deck.” She herself, a Croatian, had fallen in love with a Serbian colleague on board. “You can imagine that there were palpable national tensions on board at that time.”

The Programme Contents

Because Radio Brod was aimed at the citizens of a once united country now torn apart by war, it served listeners seeking information that was not tainted by nationalist war propaganda and ideology – as was the case with the television stations of the capitals of the former republics.

In addition to the physical war, another was raging – a media war. While the major media centres became increasingly radicalized and nationalist narratives strengthened, objective and independent information remained available mainly on the airwaves and in the services of international news agencies.

Radio Brod provided high quality, verified, accurate and balanced information to an audience caught in the maelstrom of war propaganda and subjected to manipulation. Events were presented as they actually occurred on the ground, and the most important requirement for reporting an event was truth.

The main evening news programme was broadcast at 9:30 p.m. and included information from all six republics of the former Yugoslavia. News headlines were broadcast every hour. There were also three in depth news programmes every day in the morning, afternoon and evening. The language used – Serbian, Croatian or Bosnian – depended in part on the content of the reports. In addition, news was broadcast twice daily in English and French, mainly for members of the United Nations UNPROFOR force in the region.

Here is an excerpt from a news programme:

The basis was the reports received via satellite on the ship from Reuters and Agence France-Presse (AFP), as well as the BBC World Service, and the Italian television channel RAI Uno. In addition, there were telephone contributions from numerous correspondents in the former Yugoslavia as well as in Geneva, New York, Washington and Paris. Radio Brod also exchanged information and music programmes with the brand new German satellite radio station ‘MDR-Sputnik’, the former ‘Jugendradio DT 64’. On 13 and 14 May 1993, MDR Sputnik broadcast live from the radio ship. Two German journalists (Ulrich Klaus and Martin Breuninger) were on board.

According to Klaus, Radio Brod broadcast two hours a day for the UN troops (‘Blue Helmets’): one hour in French and one hour in German. The programme was obviously heard by the troops and – as far as reactions were available – welcomed.

Dževad Sabljaković: “In special broadcasts, we connected people from opposing sides, conveyed messages, reestablished contacts, and enabled live conversations between listeners. We also offered cultural programmes as well as a very diverse and modern music programme. That’s why we were heard a lot in neighbouring Italy.”

Pero Jurišin: ”The events themselves “dictated” the programme. News was sacred. The journalists already had years of experience, were skilled reporters and had strong instincts. Therefore, it was not necessary for anyone from above to order Branka Vujnović to “address” Predrag Matvejević when he wrote a wonderful live essay on the occasion of the destruction of the Old Bridge in Mostar. Our presence on all sides of the conflict as well as our cooperation enabled us to identify developments and therefore the need for journalistic action – regardless of the form of reporting.”

These calls from all over Europe (Italy, Austria, Denmark, Croatia, France, etc.) drew in negative form a geographical map of horror, the outlines of a terra incognita, whose dark zones sent shivers down the spine: Srebrenica, Travnik, Gorazde, Vitez, etc. Thousands of such messages reached Radio Brod.

This meant that family and friends who lived in refugee camps across Europe and listened to the programme were able to find out about the whereabouts of their loved ones – sometimes even reuniting. In parallel with this humanitarian outreach work, Radio Brod broadcast psychological support programmes for children, the most vulnerable and most affected victims of the war.

Another central programming feature was the one-hour “Exodus”, which aired three times a week and offered prospective refugees practical advice on visa requirements, travel options, contact telephone numbers and the qualifications required to find work outside the former Yugoslavia. There was also practical information about the asylum procedure.

The programme provided information about legal regulations for refugees abroad and the conditions for their stay. It also gave advice on adapting to new countries and conveyed personal messages.

Darko was not only responsible for the music design of Radio Brod, but was also the creator of the floating radio station’s programme jingles, which appropriately reflected the seriousness and drama of the situation at the time and sounded anything but cheerful. An unmistakable example: seagull cries, engine noises, siren sounds – “Radio Brod is watching you.”

“Oh no, not Harry Belafonte again,” Jasmina Teodosijević rolled her eyes. Goran, a Croatian editor from Split, sighed as “Island in the Sun” played. “Once we sailed within sight of the Croatian islands and played this song,” Goran Vesić shook his head with a heavy sigh. He had been on board for three months. Petar Savić jumped up: “Croatian islands, huh? These are our islands.” Laughter around.

Michael Nicholson (ITV) reported live from aboard: ”French radio recently donated 1,000 CDs, but none have yet displaced the station’s favourite song: Bob Dylan’s ‘Blowin’ in the Wind’. And few songs fit better.“

The jngles of Radio Brod

The Interruption

Radio Brod originally wanted to broadcast a solidarity concert by Herman Brood and his Wild Romance live from Amsterdam’s Paradiso on July 1, 1993.

But by June 1993 – two months after the first broadcast – Belgrade had found a legal excuse to stop the project. Serbian authorities formally appealed to the International Telecommunications Union (ITU) and accused Radio Brod of unauthorized use of a frequency assigned to Yugoslavia. Allegedly the pirate station was interfering with the licensed broadcasts of Radio Podgorica. In addition, international law prohibits broadcasting from international waters. As well as those legal subtleties, there was a political component: Belgrade publicly accused the station of poor programme quality and questioned the credibility of the information disseminated.

That’s how Droit de Parole came to be embroiled at the centre of an international legal dispute.

The ITU then contacted neighbouring countries in the Balkans about Radio Brod’s broadcasts and eventually received a letter from the Consulate of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines in Monaco. It said that a ship flying the flag of that country was broadcasting from the Adriatic and questioned whether this was illegal. The ITU informed the consul that offshore broadcasting was prohibited under Article 422 of the 1959 Geneva Convention and was therefore illegal. But they also admitted there was little they could do if a member state ignored the agreement.

According to this information from the ITU, the government of St. Vincent and the Grenadines withdrew the registration for Droit de Parole on June 28, 1993. That same evening, a fax from the government of Saint Vincent arrived for the ship’s captain, demanding the immediate cessation of broadcasts – otherwise the vessel risked losing its flag. As a result, the Droit de Parole organisation had no choice but to return to the port of Bari, the logistical base of the operation. At a press conference aboard the Droit de Parole, now anchored in Bari, on 30 June, Dragica Ponorac, the organisation’s Secretary General, Pierre Vierl, in charge of the Bari logistics base, and Dževad Sabljaković, the station’s editor-in-chief, referred to a UNESCO declaration dated 28 November 1978. The declaration underlined the media’s contribution to promoting peace, international understanding, human rights, and the fight against racism, apartheid, and warmongering.

It explicitly highlights the importance of media that “give a voice to peoples who cannot express themselves in their own countries.”

A month of intensive discussions and negotiations followed with the relevant authorities in Europe and with St. Vincent and the Grenadines. Citing international maritime and international law that prohibits radio stations in international waters, neither France nor Italy wanted to take the risk of granting their national emblem. The organisation Droit de Parole explained in detail to the Government of St. Vincent the nature of its offshore project and emphasized that Radio Brod is supported and financed by both the European Community and a UN organisation. Just as São Tomé was about to step in to save the ship, letters of support from UN authorities and the European Commission made Saint Vincent reconsider. The Caribbean state renewed the registration – but only for three months.

After four weeks of forced waiting in the port, the ship was finally allowed to leave. On July 29, 1993, the ship resumed 24-hour operations. The well-known jingle with the cries of seagulls and a fog horn, followed by a song by The Clash (“Lover’s Rock”) – and Radio Brod was broadcasting again.

When it resumed, Radio Brod continued to use the 720 kHz frequency as those responsible were frustrated by bureaucratic delays at the ITU, where negotiations were underway to assign a different frequency. According to media reports, the broadcaster was also considering purchasing a 100 kW transmitter to achieve better coverage of its target area in the former Yugoslavia.

Droit de Parole asked the French authorities to seek official support for Radio Brod from the United Nations. The new French government, which had already rejected financial aid for the project, refused to do so, citing the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) of 1982. According to this, the states of the former Yugoslavia had the right to board the ship and stop Radio Brod’s broadcasts.

While this argument was useful to the French authorities, it was also somewhat misleading. At that point in time, the UNCLOS agreement had not yet been ratified by the required number of states worldwide and was therefore not yet part of international law.

The editor-in-chief Dzevad Sabljaković raised his thumb triumphantly: “We’re back – on the air waves and on the sea waves!” The month of silence and uncertainty was hard on morale, even if it brought some calm and the arrival of new faces on board. Laughing, he pointed to his striped T-shirt that read “Boat-People Survival.”

“I never believed that this radio station would really close down. We continued to prepare the programmes – and the new team has grown even closer together.” “This is about upholding the values that this ship created. This is my home, my nation.”

The Reception Area

The ship was equipped with a 50 kilowatt medium wave transmitter and a 10 kilowatt FM transmitter.

In cafés and bars in Dalmatia and on the Montenegrin coast, Radio Brod’s music was played for guests.

The range was very limited, often accompanied by interference. There was hardly any investment in improving the reception of Radio Brod. Against this background, the question arises as to the actual influence of Radio Brod as a source of information within the SFRY as well as the structure of its audience and listenership.

The transmissions could be received over an approximately 70 kilometre-wide strip along the coast, i.e. in parts of Croatia, Bosnia and Montenegro. Then the air waves were blocked by the central mountain ranges, but became audible again beyond the former Yugoslavian borders. This means that Radio Brod could only be received with sophisticated technical equipment in the main centers of power, in Belgrade and Zagreb, as well as in Serbia and large parts of Croatia.

Given the state of the art at the time, the range was more a question of the finances available than of what could theoretically be used as transmitting equipment. A few editors commented specifically on the problem of receiving the programmes:

Dževad Sabljaković: “Radio Brod could be received in a large part of the former Yugoslavia – in a semicircle from Istria through Slavonia and Vojvodina to Macedonia. It was also heard in war-torn Sarajevo, Belgrade and Zagreb – best of all in Dalmatia and Montenegro. However, the reception was uneven and often unpredictable. We received messages that we were being heard in Norway and Canada, while the reception in Zenica or Valjevo was very poor.”

Pero Jurišin: “The reach was geographically limited when it comes to the former Yugoslavia. The reception was weak, sometimes we could be heard in Sarajevo, occasionally in Novi Sad or even Skopje. Since there were many refugees along the Dalmatian coast, one can say that they were our most loyal listeners.”

Veselin Tomović commented as follows:

“I wish we knew what our ratings are,” said Jasmina Teodosijević. “We tell the EC we need statistics, but it’s so difficult to find out. But we know that somehow people hear us.” But the EC could hardly send someone with a clipboard into the darkest corners of the Balkans to question refugees about whether they listen to the illegal Radio Brod.

Outside the target region, Radio Brod was best received at night, when other stations on 720 kHz had closed down. The author of this article, who lives in Germany near the Dutch border, listened to Radio Brod between 2 and 5 a.m. in the spring and summer using a loop antenna. It was a pretty good signal. Chris Edwards had a similar experience in London.

The Response

The journalists on board produced reliable news and information programmes in stark contrast to the propagandistic and self-serving broadcasts of the warring parties. There were indications that even the Serbian militia and the Yugoslav secret police tuned in to Radio Brod to find out what was really going on.

As early as spring 1993, Radio Brod recorded 3,000 refugee messages. A hundred letters came from young fans of rock, jazz and rap alone.

The floating radio station was regularly criticized sharply by partisan newspapers on all sides. The Bosnian authorities denied the station’s correspondent in Sarajevo access to the official radio studios, leaving him without a satellite telephone connection. Radio Brod editor Konstantin Jovanović was outraged at the director of Bosnian radio and television who was responsible for this boycott: “He used to be a fat communist, and now he’s going out of his way for other purposes.”

On 15 May 1993, the German journalist Ulrich Klaus reported by telephone to Wolf Harranth in Radio Austria International’s ‘Shortwave Panorama’ that Radio Brod had received two difficult-to-qualify calls with death threats that were directed against the journalists and their efforts.

A Croatian weekly newspaper accused the radio producers of supporting nations that were in favour of a unified Yugoslavia and were therefore nostalgic for Yugoslavia. Serbian television also fired criticism in the direction of the Adriatic, calling the Serbian journalists from Radio Brod “sold souls.” They accused the floating radio station of being an instrument of the Ustasha and Muslim fundamentalists. Croatia, in turn, accused the radio station of supporting the Serbs.

“That’s a very good sign,” said Srdjan Kusovac ironically. His colleagues on board waved him away with a tired smile. “They are professional journalists and just want to ensure their reporting is objective, nothing more and nothing less.”

Every day the Droit de Parole received visits from two military helicopters. They flew towards the ship, circled playfully around the ship, creating artistic whirlpools on the water and then returned to their base, the US aircraft carrier “Theodore Roosevelt”. The aircraft carrier and other naval vessels were reportedly in close proximity to the radio ship. Every now and then a gray ship glided past on the hazy horizon as if guided by magic without making contact with the Droit de Parole. The crew had gotten used to the presence of the military ships. As long as NATO cruised in the sea between Italy and the former Yugoslavia, they didn’t have to fear an attack from heated nationalists.

The rush of foreign reporters was particularly large in the spring and summer of 1993. Newspapers and journals from all over the world reported on Radio Brod and wanted to get a first-hand impression on board. French (Arte, TF1‚ ‚Thalassa‘ on France 3), British (ITN), Dutch (NCRV, Super Channel), Belgian, Italian (RAI) and German (Das Erste) television channels filmed on the ship. The German-language MDR Sputnik broadcast a detailed feature about a visit on board. Wolf Harranth in the Shortwave Panorama on Radio Austria International and Jonathan Marks in Media Network on Radio Netherlands kept their listeners up to date, and BBC Radio 4 and Europe 1 also carried current reports. Bernard Kouchner, who was not only a former minister but also active with Médecins Sans Frontières, was on board the Droit de Parole ship at the end of July 1993 and was interviewed via a live broadcast on the French long-wave radio station RTL.

The Droit de Parole organisation had set up a logistical base in Bari – in an apartment hotel, the top floor of which was completely reserved. This also provided a contact point for the numerous journalists from all over the world who reported on the project. The reception there was friendly, but the inspection was meticulous. Their luggage was searched for any unpleasant surprises and their passports were retained until they returned from their visit to the broadcasting ship.

The Demise

The operation of Radio Brod was very expensive and at the end of 1993 the European institutions learned that the employees had not been paid for three months. The Paris-based Droit de Parole foundation said it could no longer pay editors’ salaries regularly due to lack of funds. It was not until the beginning of January 1994 that the wages for October 1993 were transferred.

The European Commission asked BBC foreign correspondent Jim Fish to investigate the broadcaster’s financial management both on land and on board the radio ship. Fish arrived on the Droit de Parole in an inflatable boat in early January 1994 after breakneck manoeuvres. His inspection appeared to be a direct result of a Dutch complaint to the European Commission. It appeared the French Droit de Parole Foundation had made rare and ineffective use of the total ECU 5.3 million received to support the independent press in Yugoslavia. The Dutch complaint arose from both the ineffectiveness of the broadcasts from the Adriatic, and also from what observers believe was the “poorly organized” support for the independent press in Serbia and Montenegro.

“Under the circumstances, excellent work is being done here,” said Inspector Fish after a few days. However, he was unable to clarify in Brussels what the financial situation was. “When I asked, they put a stack of folders on my table and left me to look through them myself.” Fish also remained completely unclear why Droit de Parole had no money left over for the editors’ comparatively modest salaries (around three thousand Dutch guilders per month). The seafarers on board, who were employed by a French shipping company, also reported that the payments to their company were not going well.

What was remarkable was that the journalists on board simply continued to work in January 1994 despite no salary payments. When asked, they discovered that they had not yet come up with the idea of threatening the defaulting Droit de Parole with a work stoppage. “What else should we do?” said editor-in-chief Veselin Tomović resignedly. “Most of us have been laid off at home, or if we do find work, it is only at ridiculous salaries of a few German marks a month.” Editor Konstantin Jovanović became angry: “We are all professionals and we are treated like beggars.” One reason a strike didn’t happen, younger editors said, was because their older colleagues, who grew up under communism, were far too used to keeping their mouths shut and patiently waiting to see what the authorities decide.

Dragica Ponorac considered possibly transmitting from land:

In order to stay afloat financially, the Droit de Parole organisation had already sold T-shirts with motifs by the artist Enki Bilal in the summer of 1993 (150 francs plus 30 francs shipping costs – the price for one minute of broadcasting). You could order it here: Droit de parole, BP 6, 75922 Paris Cedex 19.

Organizers claimed at a press conference in Rome the following day that they had received no warning that support was to be withdrawn. The journalists and employees were angry and disappointed.

The Droit de Parole organisation issued an SOS appeal to the Italian government. There was still hope for a potential land-based broadcaster on the Italian coast. “Italy is our last hope.” According to a report by the Italian newspaper l’Unità on 2 March 1993, the problems and prospects of the Radio Brod editorial team were discussed on the afternoon of 1 March by the journalists and the Droit de Parole spokesperson, Dragica Ponorac, at a meeting aboard the ship, which had docked in Bari that morning. That same evening, the ship set sail for Marseille, while 19 female journalists returned home – except for the three Bosnians, who still did not know where to go.

There were indications that Radio Brod went back on air briefly on 7 March 1994. At the same time, efforts were underway to secure new funding sources. However, this contrasts with a faxed response dated 7 March 1994 sent to Dutchman Ruud Poeze (then at Quality Radio), in which “Feronia International Shipping” (FISH) in Paris stated that the Droit de Prarole was back in Marseille and available for chartering as a broadcast ship for 50,000 French francs per day (plus taxes).

After the end of Radio Brod’s programming, some of the journalists continued their careers in the editorial offices of the South Slavic service of Radio Free Europe and in the BBC editorial offices focusing on the former republics of the SFRY.

The Conclusion

Radio Brod from the broadcasting ship Droit de Parole, which unfortunately only aired for eleven months, is still depressingly relevant three decades later. Today’s times of unstoppable fake news in all media are crying out for such courageous and independent journalism, which shows backbone against the background of numerous wars and merciless autocrats.

Of course, the floating radio station didn’t move any mountains, and the Balkan War continued for many years afterwards. However, the admirable journalists and technicians on the radio ship were successful and exemplary with their pluralistic reporting and their unwavering commitment to independent and truthful information. They sought open dialogue between the various ethnic and religious groups and provided humanitarian aid. They helped desperate people who were reunited with their families through Radio Brod or at least learned that their relatives were still alive and well. And it is their achievement to have at least provided some comfort and understanding for a short time to a war-torn population that suffered from the disintegration of their homeland and the omnipresent propaganda.

On this very well-connected ‘desert island’ of the media world, the Radio Brod team celebrated the honour of a free voice – armed only with microphones and their unshakable will. The history of this extraordinary radio station had a touch of madness and healthy utopia that would inspire future endeavours to protect independent journalism, information and freedom of expression. Maybe you have to raise the anchor and set sail.

Nebojša Redžić recalled in 2022: “We were lucky: the newsroom was mixed, the editorial policy anti-war, and the journalists were free in their work. It’s true, journalists from Serbia were somewhat inhibited, torn between facts and the need to satisfy the demanding Serbian public, which was more interested in myths and the ‘truth’ from Serbian sources. In one of my own broadcasts, as the waves of the Adriatic rocked me and the microphone swayed back and forth across the table, I said live that ‘a Serb can be a democrat, but only as long as Montenegro is not mentioned.’ There was a fierce reaction from the Serbian members of the editorial team.”

Belgrade media theorist Ana Martinoli interviewed some of the protagonists of this impressive radio project in 2015. Excerpts from these statements are reproduced below. More than 20 years later, the Radio Brod journalists had very positive recollections:

Dževad Sabljaković: “(The basic mission was to) provide objective and impartial information – in the joint work of journalists of all nationalities who did not harbour distrust or hatred towards other peoples, but were also critical of the elites and leaders of their own nation – in the middle of war.

Above all, it was a media project with good intentions – with the aim of preserving the dignity of journalism and the value of objective reporting.

Radio Brod was the only radio project in history that had journalists and an editorial team directly on board and whose programming was created on the ship itself.”

Ines Sabalić: “It was a human mission. An experiment to see whether, in the middle of war, those who report on it, describe it and convey it to the public can create programmes together and live together. We were actually trapped – a few of us, with different personalities, life experiences, generations and careers, in an environment we couldn’t leave. We were completely dependent on each other. We had no choice but to talk to each other – or argue.”

Dragica Ponorac: “The media space was poisoned, full of hate and intolerance. The idea of Radio Brod was to create, amid an ocean of partisan, inflammatory media, a platform that took a different, impartial approach – one that promoted tolerance and peace and aimed at de-escalation. But that was exactly what bothered all sides, which is why the station encountered strong resistance. We had the greatest satisfaction when we received letters or messages from people who had to leave their homes and, thanks to Radio Brod, found family members who were trapped in camps. The fundamental mission was a humanitarian one: to create a voice of tolerance in the midst of disinformation and warmongering media and to contribute to professional journalism.

The choice of the ship as a location was deliberate – it was intended to attract attention because it was a medium that was neither clearly on one side nor the other.”

Pero Jurišin: “Perhaps the greatest achievement of this project was that it existed at all:

- that there were people involved who were different in many ways – but not in their beliefs,

- who showed that, despite all adversities, it is possible to work together successfully, honourably and decently,

- that reason and humanity can and should win,

- that we were providing information that was “unbearably” important at that moment,

- that we were trying to tell the truth, and

- that we gave some people the certainty that their loved ones were still alive, and that they could escape the inferno and death.

What more could you ask for from your work?”

Lazar Stojanović: “It was a Promethean attempt to bring a different voice into a toxic media landscape. And I think the word “Promethean” (surpassing everything in strength and size) is exactly right.”

With thanks to Ray Robinson for his enormous help in editing and translating the text into English.

Ray also produced the following feature about Radio Brod on the DX programme Wavescan (11 May 2025):

The Sources:

Algemeen Nederlands Persbureau (ANP) 02-07-1993

Aonuma, Satoru: Alternative Media and the Unwiring of the Global Village: Reappraising International Radio Broadcasting in the 21st Century. Paper presented at the National Communication Association Annual Convention Held in Las Vegas, NV, November 2015

Bastic, Jasna. Help and hope from Radio Boat. The European 30-09-1993

Beham, Mira: Den Krieg in den Medien beenden. Süddeutsche Zeitung (September 1993)

Breuninger, Martin: Radio Brod – Friedenssender für Ex-Jugoslawien. RADIO-Hören 5-1993

Breuninger, Martin: Radio Brod – Das Radioschiff. MDR Sputnik 23-06-1993

Van den Boogaard, Raymond: Op zee, een somber maar heel Jugoslavië. NRC Handelsblad 15-01-1994

Chicago Tribune. October 14, 1993. https://www.chicagotribune.com/1993/10/14/yugoslav-pirate-station-comes-complete-with-ship/

Colonna d‘Istria, Michel: „Radio-Bateau“, antenne haut. Le Monde 02-08-1993

Eagar, Charlotte: Desperately seeking Bosnia’s truth. The Observer 19-09-1993

Eagar, Charlotte: ‚Pirate‘ radio broadcasts to Balkans. The Telegraph 23-09-1993

Fantom slobode. Emisija 04-10-2011: ili pokušaji bekstva. https://pescanik.net/fantom-slobode-2/

Harranth, Wolf: Kurwellenpanorama. Frühjahr und Sommer 1993

Harranth, Wolf: Seesender für Meinungsfreiheit in Jugoslawien. Kurier 12-1993

Horne, A.D.: Dispute torpadoes ‚Boat Radio‘. Washington Post 26-09-1993

Kurt, Erbil und Pinkau, Rainer: Die Segel gestrichen. Journalist 8-1993

Leonard, Mike: Offshore Radio Museum. http://www.offshoreradiomuseum.co.uk/page582.html

Martinoli, Ana: Kreiranje Alternativnog Medijskog Prostora u Trenutku Raspada Jugoslavije – Programski i Produkcioni Aspekti Projekta Radio Brod. Beograd, 29-30. Oktobar 2015

Marks, Jonathan: Media Network. Radio Netherlands (14-04-1993, 09-09-1993, 10-02-1994, 24-02-1994, 03-03-1994)

Nebojša Redžić: Laž ponekad dolazi sa Zapada, naravno na srpskom. 13-06-2022. https://portalluca.me/medijsko-reketiranje/laz-ponekad-dolazi-sa-zapada-naravno-na-srpskom/

Nebojša Redžić: Radio Brod. 01-10-2013. https://nebojsaredzicc.wordpress.com/2013/10/01/radio-brod-2/

Noethen, Sabine, In: Weltspiegel (Das Erste, ARD). 16-08-1993

Offshore Echo’s Magazin (Issues 94, 95, 96 and 98) (1993/94)

Parkes, Jim: The Encyclopedia of Offshore Broadcasting (Edition April 2024)

Pedersoli, Alessandra e Toson, Christian: Onde libere e rock ‘n’ roll. La rivoluzione delle emittenti ofshore. In: La rivista di engramma 174 (luglio/agosto 2020)

Quaranta, Luigi: Belgrado fa tacere la radio multietnica Appello all’Italia. l’Unita 01-07-1993

Radiojournal 6-1993

Radio von unten 6-1993

Raspiengeas, Jean-Claude: La Voix de la You. Télérama 23-06-1993

l’Unità 02-03-1994. E da Radio-Brod nuovo Sos.

Vivarelli, Niccolo: Free Press on the High Seas. Newsweek 30-08-1993

Zordan, Nicola: Radio brod, controinformazione in mare aperto. https://www.meridiano13.it/radio-brod-controinformazione-in-mare-aperto/