The 258-foot-long Gorsethorn, formerly known as Dido 77, was built in 1963 by Charles Hill & Sons Ltd in Bristol, England, and served as a cargo and surveying vessel. The now rust-brown-painted, 1,140-ton heavy freighter was adorned with massive Chinese characters in the spring of 1990. At the bow of the radio ship was a replica of the

The “Déesse” was registered in Saint Vincent and had been overhauled by Marine Services Convoyages in La Rochelle. The future broadcasting ship was intended to broadcast radio messages from and for Chinese dissidents on June 3rd and 4th, 1990, the anniversary of the bloody crackdown on protesters in Tiananmen Square. Plans were made to put the radio transmitters into operation by April 27th, exactly one year after the initial Chinese unrest against the government.

The project was extremely ambitious, arousing huge expectations and global media interest. The goal was to disseminate the truth about the Chinese democracy movement, the massacre by the army, the suppression, and the terror. And about the resistance slowly rebuilding even within the People’s Republic. Chinese dissidents who had fled the country in June 1989 were supposed to send their messages to China from the ship. One of the initial programs was to include a 20-minute prerecorded report by student Chai Ling. Leading dissidents Wu Er Kaixi, Shen Tong, and Yan Jiaqi were also planned to make their voices heard on air. In addition to radio broadcasts, the crew of the “Goddess of Democracy” intended to transmit television messages from international waters to the mainland. These were to be defiant calls for democracy, accompanied by rock music.

The organizers stated that the ship would use Taiwan as a base to refuel and replenish supplies in the East China Sea between broadcasts. They claimed that the funding allowed for continuous broadcasting around the clock for two months.

The christening of the ship was attended by many prominent figures. The French chansonnier and actor Yves Montand ironically quoted from the Mao Bible, and the philosopher André Glucksmann declared it “a duty to get involved.”

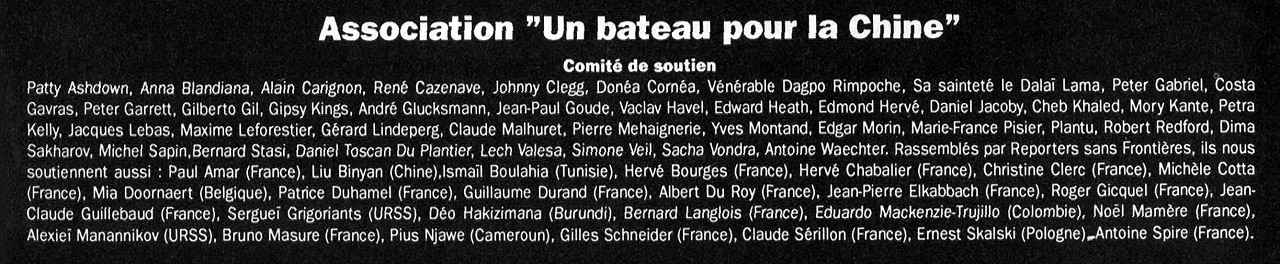

The journey was meticulously prepared. In the fall of 1989, the association “A Boat for China” was founded in Paris. Members included the Federation for Democracy in China (FDC), the largest organization of Chinese dissidents abroad, as well as 16 magazines in Europe and America, including “Actuel” in France and “Tempo” in Germany.

On March 17, the future broadcasting ship left the French port of La Rochelle. The destination was the Formosa Strait between Taiwan and the Chinese mainland. On board were eleven French sailors, several TV teams and journalists, and a crate of ready-to-broadcast tapes.

Each time, the crew had to muster all their energy to avoid panic. By now, Beijing had spread the threat that it would by no means tolerate the planned radio broadcasts. “This ship is a tool of the reactionary organization Front for Democracy in China. Its goal is to undermine the People’s Government,” said Foreign Ministry spokesperson Li Jinhua at a press conference on April 26. “It is something we cannot tolerate.” A French politician was even told, “We also know how to deal with an unwelcome ship” – a thinly veiled reference to the sinking of the Greenpeace ship “Rainbow Warrior” by the French intelligence service in July 1985. “We will not tolerate any country that helps the ship,” said the spokesperson. “Its activities aim to undermine the government of China.” Beijing did not rule out using violence to prevent the ship from broadcasting.

“The government is afraid because the Communists exert pressure,” argued Michael Chen, a member of the “Boat for China” project based in Taiwan. “But the people in Taiwan will let this ship come here. The civilians, the fishermen, they will support it.”

Despite all adversities, the “Déesse de la Démocratie” covered around 20,000 kilometers in 8 weeks and sailed all the way to Taiwan. On May 13, all threats seemed to be forgotten. Freshly cleaned and flagged, the “Goddess” entered the port of Keelung on May 13. School classes, brass bands, and several carloads of ministers, influential businessmen, and government officials waited at the pier to give the ship a triumphant reception. Thousands waved flags and cheered. The ship was the top story in the main news broadcasts of all Asian countries for days. Television crews jostled at the dock to be allowed on board. Newspapers worldwide, from the “International Herald Tribune” to the “Taz,” reported on the arrival of the radio ship.

The plan to broadcast to China had failed. Bizot and the FDC wanted at least to broadcast on June 4, the first anniversary of the Tiananmen massacre. The Japanese television network “TV Asahi” had offered assistance, Bizot said at a press conference. “We will go with the ‘Goddess’ to Japan, install a transmitter there, and broadcast from international waters.”

After lengthy deliberations, the Japanese government then denied visas to the ship’s crew. They did not want to jeopardize excellent economic relations with Beijing… On May 21, Japan thus became the third Asian country, after Hong Kong and Taiwan, to give in to Beijing’s pressure. The decision indicated a growing regional reluctance to confront Beijing’s hardliners. It marked a remarkable turnaround. Just a year ago, the Chinese leadership had been harshly criticized throughout the region for the army’s massacre. Now, however, the neighboring states apparently feared provoking China’s hardliners at a time when Asia’s most powerful economies wanted to strengthen trade relations with China. After all, it was the largest source of cheap labor and abundant resources in the region…

What would happen next with the “Déesse”? In April 1991, Taiwanese businessman Wu Meng-wu bought the ship for $550,000 from the China Shipping Association based in France, a group founded by Chinese dissident leader Yan Jiaqi living in exile in Paris. Later, he transformed the ship into a floating museum displaying photographs and information about the bloody suppression of Chinese pro-democracy activists on Tiananmen Square in Beijing on June 4, 1989.

The Mainland Affairs Council (MAC) urged the semi-official “Alliance for the Reunification of China under the Three Principles of the People” to buy the ship. The offer was rejected on the grounds that the alliance did not have sufficient funds.

The Kaohsiung Harbor Administration asked the MAC to reach an agreement with Wu Meng-wu to scrap the ship, which had been lying in the harbor since 1991 without paying fees. Chen Chin-fung, harbor administrator, stated that the ship was two to three degrees tilted, heavily rusted, and had safety issues.

In September 2003, Taiwan began scrapping the radio ship “Déesse de la démocratie”, which had been in the shipyard since 1990. The demolition work, expected to take about 70 days, began after a ceremony in Anping, a port in southern Tainan County, said Wu Meng-wu, the ship’s owner. “This is a blow to those who have stood up for freedom and democracy in China,” a furious Wu told AFP in a phone interview.

In March 2003, Wu was instructed to scrap the ship after losing a legal battle against the port authorities of Anping, who insisted that the ship had to be removed to make room for the harbor expansion, and that Wu had to pay at least two million Taiwanese dollars (about $58,650) in harbor-related fees. Wu agreed to dismantle his ship by September 10 but denied owing any fees to the authorities. Wu claimed that the government had promised to help him after the purchase of the ship.

Martin van der Ven (2024)