By Hans Knot

Radio broadcasts from ships have played an important role in international waters off Western Europe, often aiming to challenge government control over radio waves—and with success. Of course, there have been similar attempts outside Europe, with two major examples being Radio Hauraki off the coast of New Zealand and The Voice of Peace for the people of the Middle East. Off the U.S. coast, there was Radio New York International, which was quickly shut down by the authorities. Naturally, there have also been several failed political projects, such as Radio Brod during the Balkan crisis.

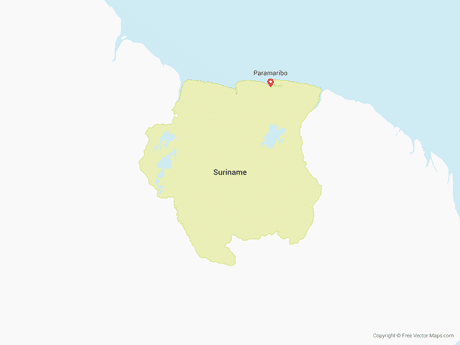

However, little to nothing has been written about the plans for a politically oriented offshore radio station targeting the government of the then-young state of Suriname in the mid-1980s. In 2007, Hans Knot came across a number of slide negatives and decided to finally make public the knowledge that he and Rob Olthof had gathered at the time.

In 1975, a grand celebration took place in Suriname, as the country gained independence from the Netherlands, believing itself strong enough to establish its place in the world as a sovereign nation. But was the country truly ready to develop into a well-functioning state? Different groups had varying opinions about independence, largely shaped by their circumstances.

The Creoles were the strongest proponents of independence. As a sizable portion of the population, they felt confident in their ability to lead the new nation. Their political leader, Henck Arron, made this clear when the Creoles won the 1973 elections and immediately pushed for independence. The Hindustani community, however, had mixed feelings—while some supported independence, others saw no issue with remaining part of the Netherlands. Meanwhile, the Javanese believed it would have been far better for Suriname to remain a Dutch territory.

There was also a modest number of Dutch nationals living in Suriname at the time. Like the Javanese, most of them believed Suriname should remain under the Netherlands’ protection and opposed the creation of an independent state.

So, it all seemed like a grand celebration when Suriname finally gained independence, but the joy was short-lived. The country had been under Dutch rule for so long that independent decision-making and self-governance were unfamiliar concepts for its people. In fact, during the first years of independence, 90% of Suriname’s funding came from the Netherlands. This was essentially development aid, making the new nation even more dependent on its former colonial ruler. Moreover, the politicians of the young state had no real idea how to govern, and everything quickly started to go wrong.

While the independence treaty allowed the Dutch government to influence Surinamese politics under the Development Cooperation Agreement, the Netherlands chose not to intervene.

As a result, corruption flourished, elections were plagued by fraud, and nepotism took hold. Eventually, the situation in Suriname deteriorated to the point where even in the Netherlands, confidence in the parliamentary democracy there was lost. An infamous date remains February 25, 1980, when a group of sergeants staged a coup and successfully installed Desi Bouterse as their military leader, head of government, and chairman of the country’s highest political authority, the “Topberaad” (High Council). It didn’t take long for many Surinamese and the Dutch to realize that Bouterse was the wrong choice. He ruled with an iron fist, eliminating opponents and crushing protests. In December 1981, at least fifteen people were executed for opposing his regime.

This occurred during the presidency of Henk Chin A Sen, who was appointed in 1980. Born in Albina, Suriname, Chin A Sen studied medicine at the Medical School of Paramaribo and graduated in 1959. He worked as a general practitioner until 1961, after which he moved to the Netherlands to specialize in internal medicine. Upon returning to Suriname, he worked at the St. Vincentius Hospital in Paramaribo and joined the Nationalist Republican Party (PNR), which supported Suriname’s independence, though he was not an active member.

On March 15, 1980, following the Sergeants’ Coup that brought Bouterse and his military council to power, Chin A Sen was unexpectedly appointed Prime Minister of Suriname. He formed a leftist government that included two members of the National Military Council (NMR). However, it soon became clear that he was committed to restoring democracy and limiting the power of the NMR.

Due to internal conflicts within the National Military Council (NMR)—which eventually led to an internal coup by Bouterse within the NMR—Henk Chin A Sen was initially able to strengthen his position. However, once the NMR regained control, a serious conflict arose between Chin A Sen and Bouterse in 1981 over the direction the country should take. Bouterse aimed to establish a socialist and revolutionary society, with the NMR pulling the strings in the background, while Chin A Sen sought to restore democracy. In 1981, the NMR rejected a draft constitution proposed by Chin A Sen, escalating tensions between the government and the military.

Chin A Sen’s birthday celebration on January 18 at the presidential palace was used by his supporters as a demonstration against the NMR’s power. On February 4, 1982, Chin A Sen resigned after failing to reach an agreement with Bouterse on the allocation of Dutch development aid and the draft constitution. He left the newly independent Suriname and went into exile in the Netherlands. After the December 1982 murders, he was elected chairman of the Council for the Liberation of Suriname, which opposed Bouterse’s regime from the Netherlands—though with little success. Chin A Sen later connected with Ronnie Brunswijk and his Jungle Commando, which waged an armed struggle against Bouterse.

Opposition could, of course, take many forms, such as financing Brunswijk’s Jungle Commando, which often, albeit secretly, held meetings in the Netherlands. At one such gathering, Chin A Sen met Steph Willemse, who had previously attempted to set up two offshore radio projects. Inspired by Willemse’s stories, Chin A Sen agreed that same evening to meet again and explore the possibility of launching a similar project off the coast of Suriname.

After several discussions, the two concluded that, provided they secured sufficient funding, Willemse and his associates would prepare a ship to serve two purposes. The vessel would operate as a temporary radio ship in international waters off Suriname’s coast, broadcasting messages advocating for the country’s democratization—something Bouterse and his regime strongly opposed. Additionally, Chin A Sen envisioned another use for the ship: as a troop transport. Small groups of ‘fighters’ could board in international waters and, under the cover of night, approach the Surinamese coast to join Brunswijk’s guerrilla forces.

Chin A Sen and Willemse set out to find a suitable ship, eventually locating one in the port of Scheveningen. The MV Maria (SCH33), a former fishing trawler, was inspected and deemed fit for the mission. A down payment was required to secure an option on the ship through a broker. Chin A Sen’s direct contacts and financial resources provided the initial funds, while Willemse sought additional investors to equip the vessel as a broadcasting station. The former president also hoped to persuade former Surinamese nationals living in the Netherlands to participate in the project.

One of the first people Steph approached for radio transmission equipment was Edje Bakker. He asked him about the possibility of acquiring one or more “Harrys”—American-made transmitters that were being dumped on the Dutch market at the time. These transmitters were widely used by land-based pirate stations like Radio Centraal in The Hague and Radio Unique in Amsterdam. Steph wasn’t only thinking about the Surinamese project but also about his own future. If the radio ship returned after completing its mission for Suriname, it could be repurposed for offshore broadcasting off the Dutch coast. In that case, the FM-compatible Harry transmitters would be crucial.

The first funds were spent, and the Harrys were delivered to Steph’s place in Haarlem. One of the people he contacted was Rob Olthof, an avid offshore radio enthusiast since the early 1960s. Olthof had previously interacted with Willemse:

“In 1973, Hans Knot, the then-editor-in-chief of Pirate Radio News—whom you probably know—asked me to interview Steph Willemse. At the time, Steph’s radio ship, the MV Condor, was anchored in international waters off the coast of Zandvoort. To meet him, I had to go to his home at Rijksstraatweg 683 in Haarlem, where he lived with Fietje van Donselaar.

During that first meeting, Steph told me that Radio Condor would broadcast on 270 meters (AM), featuring various religious groups and evangelists speaking on air. He also had a clear vision for the station’s music format, as he was a huge jazz and blues fan. So, he promised that this genre would be a regular part of the programming. The following Saturday, he invited me to visit his ‘plaything’—the radio ship. The plan was to take a tender from the port of IJmuiden to the vessel.

That Saturday afternoon, I first visited my favorite seaside town, Zandvoort. On my portable radio, I picked up some faint beeps and blips on 1115 kHz. The test tones were so weak that I had to turn the volume all the way up to hear anything. Unfortunately, those test signals were all that ever came of it. A major technical failure and financial troubles forced Willemse to sell the ship. However, it eventually made it on the air as Radio Atlantis under the leadership of the Belgian broadcaster Adriaan van Landschoot.”

That wasn’t Steph Willemse’s only failed project in the 1970s. Rob Olthof continued:

“Steph was also involved in the planned broadcasts of the SOR (a project by Bob Peeters from Haarlem). The ship resembled a small weekend boat and had a few illegal Portuguese immigrants on board. Bob Peeters had absolutely no knowledge of offshore radio, and to my surprise, he told Steph and me that he was planning to have dockworkers drill a pole straight through the middle of the ship to serve as an antenna mast. Naturally, nothing ever came of that plan.

I stayed in touch with Steph, even after he moved to a beautiful house in Kenaupark, Haarlem. A few years later, the Dutch Radio Control Service confiscated a transmitter from his home—it was meant for Radio Delmare. That station was active in the late 1970s, led by Gerard van Dam, with Steph involved in the project. Peter Chicago was reportedly the one who modified a surplus military transmitter to be used by Radio Delmare. One Saturday morning, Steph called me, telling me to avoid phone contact for the time being, as Gerard van Dam was testing the transmitter in the port of Scheveningen.”

A few years passed after Steph’s involvement with Radio Delmare before he became engaged in another offshore radio project—this time, the aforementioned plan for a station off the coast of Suriname. He made phone calls to Amsterdam, including one to Rob Olthof, to see if he could find people willing to participate in the project. Strangely enough, despite Olthof’s knowledge of Willemse’s past failed ventures, he found the idea intriguing and even considered financially investing himself. An invitation followed for further discussions.

Rob Olthof: “This time, around mid-1984, Steph was much more driven than in previous projects, and his story about Henk Chin A Sen inspired me to continue the conversation. He explained the dual purpose of the project and how it was intended to be financed. Steph mentioned that Dutch investors would eventually be able to recover their funds. The plan was that within six to nine months, the impact of the radio ship off the Surinamese coast would achieve its goal—replacing the Bouterse regime with a more democratic government. Upon the ship’s return, it would shift to broadcasting a more commercial message off the Dutch coast, benefiting the larger investors.”

Olthof became increasingly intrigued. After four discussions, he was convinced and contributed a substantial amount from his personal funds to Steph’s venture. Soon, he was invited to inspect the future radio ship, which had already been partially paid for by Henk Chin A Sen.

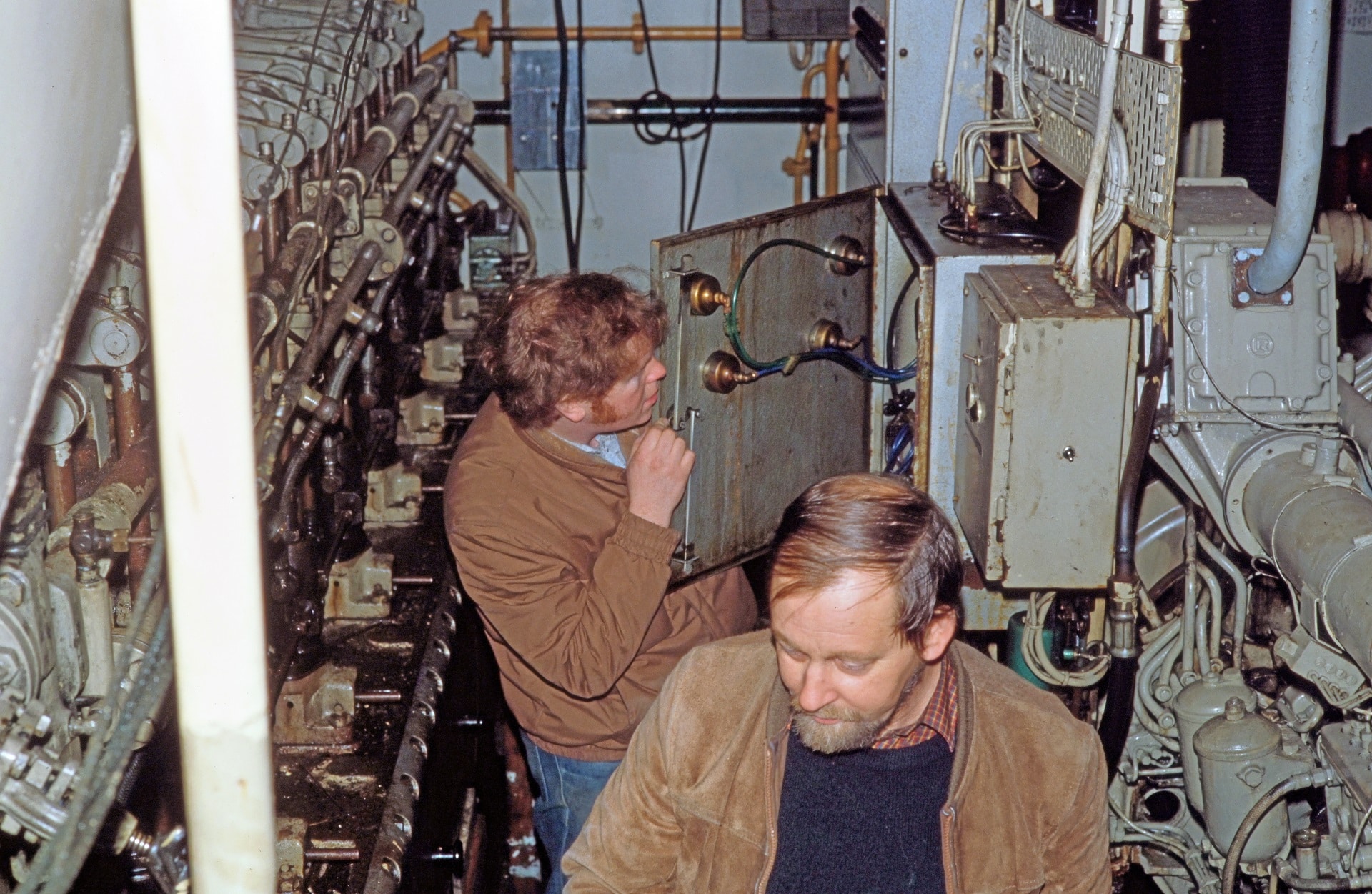

Olthof: “Like many fishing vessels at the time, the future radio ship MV Maria was laid up in the port of Scheveningen, and we went to visit it. From the outside, it looked well-painted, and the interior had been adequately prepared for a decent start. The ship had been freshly painted, and the engine room was in excellent condition. I felt confident that my money was well-invested and would be easily recovered.”

Meanwhile, Steph dug out his extensive record collection in Haarlem to contribute to the project. A mobile studio was also set up, which could be used during gatherings and parties held by Surinamese communities in the Netherlands. Through organizing drive-in shows, Sen’s fellow countrymen were encouraged to donate funds to the liberation project.

All of Chin A Sen’s activities were aimed at overthrowing the Bouterse regime. He was actively involved in the Council for the Liberation of Suriname, which had an office in Rijswijk. However, Bouterse and his allies had enough contacts in the Netherlands to closely monitor the council’s activities.

In March 1985, the Netherlands was shocked by a brutal attack on the Council for the Liberation’s office. The true motive behind the attack was never fully clarified. Three members of a music band were killed. At the time, media reports suggested that Henk Chin A Sen was also in the building, though this was never confirmed. The attack left him deeply shaken, leading him to reconsider his priorities. He ultimately decided to focus on leading a normal working life rather than continuing with the planned activities.

Olthof: “Overnight, it became clear that once again, Steph’s dream of launching an offshore radio station would not materialize. All the equipment had been procured or was on order. Henk Chin A Sen had already made a down payment on the future radio ship, which was held by a shipbroker.

However, following the attack, the remaining balance was never paid, and the option expired. It was an expensive dream for all of us, one that, as of 2007, only lives on in our memories and old slides capturing brief moments in time.

Henk Chin A Sen passed away in 1999, while Steph Willemse died in 2004.“

33 photos: An ill-fated project for Suriname

More information about the MV Maria (Scheveningen 33)

Sources:

Knot, Hans. (1991). De Kleintjes van de Noordzee. Deel 2: Atlantis, Condor, S.O.R., Seagull, Carla en Dolphin. Amsterdam: Stichting Media Communicatie.

Knot, Hans. (1993). Historie van de zeezenders 1907-1973. Over pioniers, duimzuigers en oplichters. Amsterdam: Stichting Media Communicatie.

Knot, Hans. (1994). Historie van de zeezenders. 1974-1992. Meer duimzuigers en mislukkelingen. Amsterdam: Stichting Media Communicatie.