A Floating Media and Communications Centre in the Atomic Age

![]() Nederlandstalige versie –

Nederlandstalige versie – ![]() Deutschsprachige Version

Deutschsprachige Version

Able Day (Test Able) was the first of two nuclear weapons tests conducted by the United States as part of Operation Crossroads on 1 July 1946 (local time) at the remote Bikini Atoll. A B-29 bomber dropped a bomb (“Gilda”) which detonated at an altitude of approximately 158 metres, with a yield of 23 kilotons, above a fleet of 73 target ships. The primary objective was to investigate the effects of nuclear weapons on warships. The bomb missed its intended target (USS Nevada) by about 650 metres. Despite this error, five ships were sunk. Radioactive contamination was short-lived, but the effects on the test animals placed aboard the vessels were severe. It was the first nuclear test to take place in the presence of the world’s press and international observers.

The atomic bomb had brought the Second World War to an end, yet its strategic, political and media significance was still largely unexplored. At that moment, the world stood on the threshold of a new era.

For the first time, a military–scientific experiment of this magnitude was not only to be conducted, but also documented, communicated and publicly explained almost in real time. Within this field of tension between military secrecy, political signalling and public information operated a vessel that received little public attention, yet was of central importance to the conduct of the operation: the Army Communications Ship USAT Spindle Eye.

Lieutenant Colonel M. J. Luichinger, the officer in charge and at the same time the chronicler of the project, provided in his report for the American magazine Radio News in December 1946 one of the few contemporary insider accounts of this floating communications and broadcasting centre.

According to his description, the ship was far more than a mere technical aid. It was a nodal point at which military command, scientific experimentation, worldwide public relations and advanced communications technology converged.

Communication as the Invisible Backbone of Operation Crossroads

Luichinger repeatedly emphasised that reliable communications constituted the central element of the entire operation. “Each unit with its own individual function … would have been worthless to the overall objective without reliable communications,” he wrote. While many contemporary accounts focused on the explosion itself, the aircraft, the measuring instruments or the target fleet, the complex communications infrastructure largely remained in the background—an omission that Luichinger explicitly criticised.

The operation involved approximately 42,000 participants, distributed across islands, ships, aircraft and command centres on both sides of the Pacific. Accordingly, the forms of communication were highly diverse: strategic command links between Bikini, Kwajalein and Washington; tactical radio networks between the flagship and subordinate units; remote control of unmanned aircraft; transmission of meteorological data; remote operation of cameras and measuring devices; and, not least, the media presentation of events to the American public.

It was precisely this final aspect that gave the Spindle Eye its particular significance. Luichinger expressed it succinctly: the ship’s task was “to keep the American public informed on what was going on 10,000 miles away from home”.

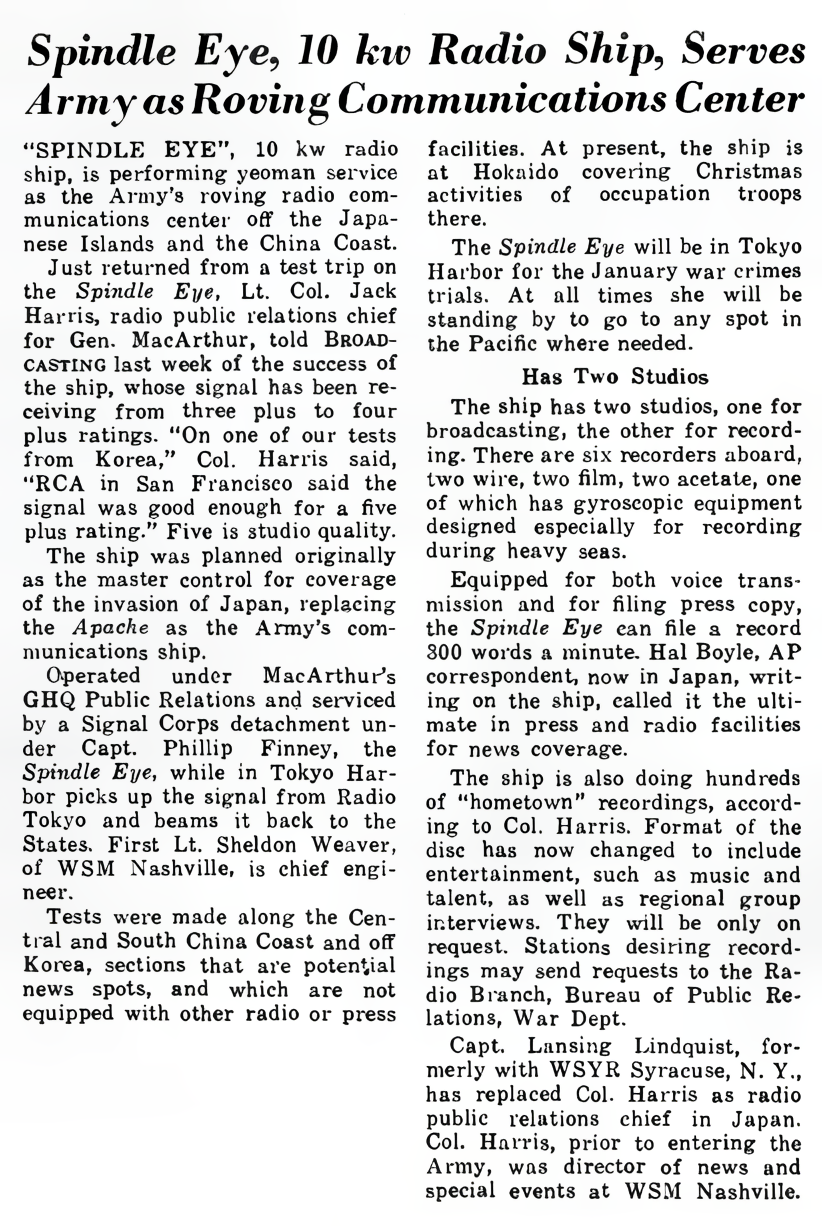

Excursion: Background History of the Radio Ship

Plans for the radio ship Spindle Eye were developed during the course of 1944. It was intended for deployment as part of the planned invasion of Japan.

This new radio ship was laid down at the Kaiser shipyards in Richmond, near San Francisco in the U.S. state of California, and was launched on 25 May 1945 under the unassuming name Spindle Eye. The vessel was almost 340 feet long and 50 feet wide, with a total light displacement of 4,000 tons.

Originally, the Spindle Eye was constructed as an army cargo ship, but it was taken over and, within a short period of time, equipped with a wide range of electronic installations at the Todd shipyards in Seattle, Washington. On board were two radio studios, six shortwave transmitters, eight antennas, and 112 typewriters. Four of the shortwave transmitters were 3 kW units manufactured by Wilcox; the high-quality 7.5 kW broadcast transmitter was built by RCA at its factory in Camden, New Jersey.

The first series of test transmissions from the Spindle Eye took place during the first half of September 1945 at the dockside shipyards in Seattle, using the 7.5 kW RCA transmitter. On 19 September, after only 64 days of fitting-out and conversion, the ship sailed into the Pacific, bound for Japan.

The Spindle Eye arrived in Tokyo harbour on 15 October and assumed the radio services previously provided by the Apache under the callsign WVLC; that vessel was still in the Philippines at the time. The Spindle Eye was inspected by General MacArthur and subsequently undertook a trial voyage in the waters off China and Korea. It was reported that the electronic equipment on board the Spindle Eye was functioning flawlessly.

After returning to Japan shortly before Christmas, the Spindle Eye, operating under the transferred callsign WVLC, began a series of broadcasts on behalf of the Voice of America and the American Armed Forces Radio Service. In addition, reports on the legal trials held in Tokyo in 1946 were relayed from the Spindle Eye to the United States, where they were rebroadcast nationwide.

A Floating High-Performance Broadcasting Studio

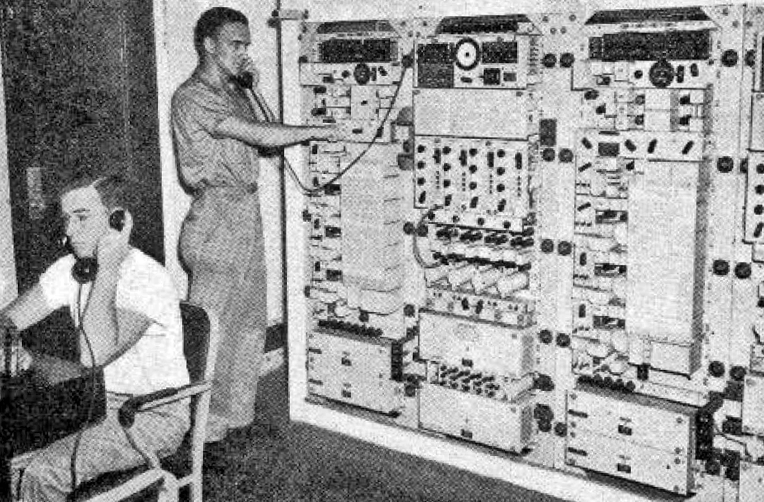

From a technical perspective, the Spindle Eye was a masterpiece of post-war engineering. At the time of Operation Crossroads, on board were, among other installations, a 7.5 kW RCA shortwave transmitter, a Hallicrafters BC-610, a Wilcox 96C four-channel transmitter, high-speed teletype equipment capable of up to 500 words per minute, Acme radiophoto transmission systems, as well as extensive studio, recording and mixing facilities.

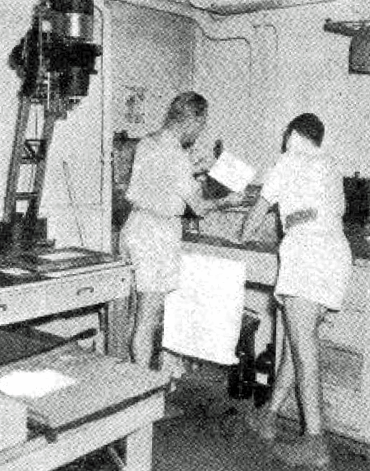

The ship housed several broadcast studios, a central control room with an extensive patching infrastructure, Western Electric compression amplifiers, numerous receivers (including Hammarlund Super-Pro and RCA AR-88 models), a fully equipped darkroom, and an air-conditioned press conference room with 120 typewriter positions. Luichinger pointed out with evident pride that all studios and technical spaces were fully air-conditioned—no small advantage in the tropical climate of the Marshall Islands.

Particularly noteworthy was the flexibility of the signal routing. Via the central patch panel, voice, teletype and image transmissions could be combined at will. Transmitters nominally assigned to broadcasting could just as easily be used for teletype or radiophoto transmission—a concept that was far ahead of its time.

Antennas, Anchors and Technical Improvisation

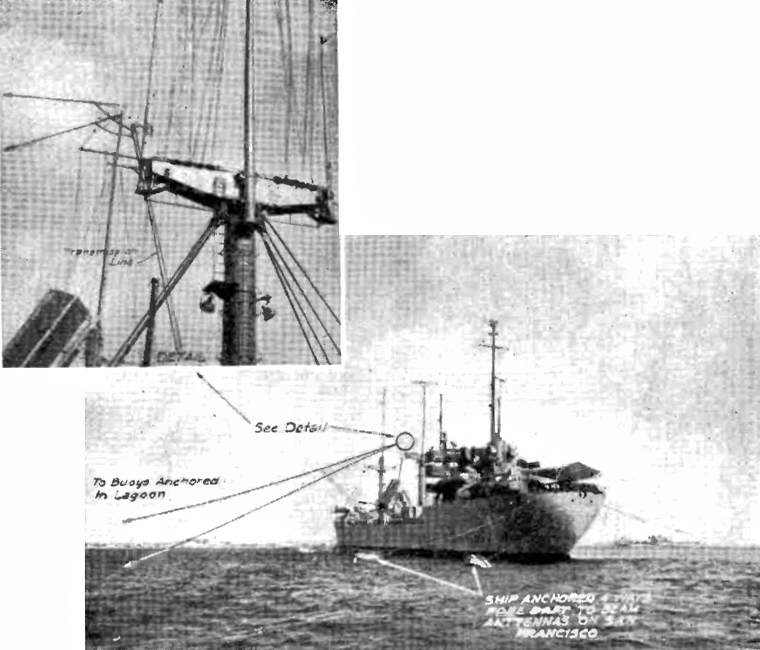

One of the greatest technical challenges arose from the geographical position of Kwajalein and the prevailing winds in the area. The conventional delta-fed doublet antennas radiated their maximum power at right angles to the ship’s axis—an unfavourable orientation for the desired link to the US West Coast. Luichinger describes in detail how the ship was permanently fixed on a heading of 143 degrees by means of a four-point anchoring system in order to align the main radiation lobe precisely with the great-circle path to San Francisco.

Even this proved insufficient. In a remarkable act of technical improvisation, an inverted, unterminated V antenna was constructed, its legs leading to buoys anchored in the lagoon. “We admitted at the time that the idea sounded rather wild,” Luichinger wrote, yet the outcome was convincing: an improvement in signal strength of approximately 30 per cent.

Equally innovative was the establishment of a remote receiving station at the northern tip of Kwajalein Island, connected to the ship by so-called spiral-four cables simply laid on the lagoon floor. This measure drastically reduced interference and made reliable cue signals from the United States possible in the first place.

A-Day: Media Event and High-Load Operation

On Able Day, the day of the first atomic test, the Spindle Eye demonstrated its full operational capability. Live reports on evacuation measures began as early as 03:30. These were followed by outside broadcasts of the take-off of a B-29 bomber, pooled broadcasts after the signal “Bombs Away”, parallel voice and image transmissions, and the onward relay of the first photographs of the explosion via Hawaii to San Francisco.

Luichinger describes this day as a near-continuous state of exception. The transmitters operated in parallel, all voice broadcasts were recorded as a precaution, and between programme segments the technical operation constantly switched between sound and image transmission. That only two brief interruptions occurred during the entire operation was, in his view, evidence of the quality of maintenance, planning and personnel.

The People Behind the Technology

Despite all the technology, Luichinger repeatedly emphasised the human factor. He explicitly praised his team—many of whom had civilian broadcasting experience—for their expertise, improvisational skill and dedication. “Our success … was possible only because of the high calibre of boys I had with me,” he wrote, making it clear that even the most advanced technology was worthless without qualified personnel.

What Happened Next

The Baker Test was an underwater nuclear test conducted by the United States on 25 July 1946 at Bikini Atoll as part of Operation Crossroads. A bomb with a yield of 23 kilotons was detonated at a depth of 27 metres, creating a vast radioactive column of water and debris that sank several ships — including the USS Saratoga — and caused extreme and unexpected contamination of the fleet.

At that time, the radio ship Spindle Eye was stationed in Honolulu and served as a relay point between the atomic test sites in the Marshall Islands and the American mainland. During the underwater nuclear explosion, the Spindle Eye, operating under the callsign NIGF, received shortwave reports from Bikini and relayed this programme to RCA Bolinas and Press Wireless Los Angeles for further distribution.

Following the two atomic tests, the Spindle Eye returned to the Pacific coast of the United States, and operation of the transmitter under the callsigns WVLC–NIGF came to an end at the close of 1946. The radio ship had originally been intended for use in the planned invasion of Japan, but the war ended before the vessel could be deployed in that role.

The Spindle Eye was occasionally used under the callsign WVLC for the broadcast of Voice of America programmes and for the relay of news reports.

One year later, the Spindle Eye was renamed Sgt. Curtis F. Shoup and was deployed in the Pacific as a helicopter transport ship. After this period of service ended, the vessel was transferred to the Mediterranean, where it was used for oceanographic research. The ship, known successively as Spindle Eye and Sgt. Curtis F. Shoup, was ultimately sold for scrap on 9 May 1973.

Critical Assessment of the Spindle Eye in the Context of Operation Crossroads

From today’s perspective, the Spindle Eye appears as a technically impressive yet deeply ambivalent symbol of the early atomic age. As a floating broadcasting and communications hub, it enabled an unprecedented media staging of military power. It is precisely in this role that its problematic dimension lies.

The technical perfection and operational reliability described by Lt. Col. Luichinger served an operation whose health, environmental and political risks were either insufficiently understood in 1946 or consciously accepted. The broadcasts and press reports disseminated via the Spindle Eye contributed significantly to presenting the nuclear tests as controllable and technologically manageable events. The real dangers of ionising radiation, the long-term contamination of sea, islands and ships, and the consequences for participating personnel and the local population of the Marshall Islands were largely excluded from public discourse.

The Spindle Eye was therefore not merely a neutral communications platform, but an instrument of strategic public relations. It conveyed proximity, transparency and technological mastery, while uncertainties, failures and later health effects were scarcely addressed. In this sense, it contributed to the normalisation of nuclear violence by translating the atomic test into a media event framed by familiar formats—live commentary, eyewitness reporting and images.

At the same time, the Spindle Eye exemplifies an early entanglement of military, science and media whose consequences extend into the present day. It stands for the beginning of an era in which military mega-experiments were not only conducted, but also carefully orchestrated in communicative terms—with lasting effects on public perception, political decision-making and the understanding of technological risk.

In historical assessment, the Spindle Eye thus represents a dual legacy: a milestone in communications engineering and media organisation, and at the same time a warning symbol of the ethical blind spots of an age that placed technological feasibility above long-term human and environmental consequences.

Martin van der Ven, Januar 2026

Sources:

Broadcasting December 24, 1945

© Fotos: Oliver Read (Radio News)