Hans Knot goes back in offshore radio history to the period between 1979 and 1981. This is in response to a photo received of the ship Quo Vadis. This ship is better known as the MV Manor Park and was to be used by some guys including Ian Biggar, Ken Baird, Barry Lancaster and Chris Cortez and later Kevin Turner and Stuart Clark for a new offshore radio project. Radio Ventura and Radio Free England were to broadcast from the MV Manor Park.

I regularly visit the website about coasters in Groningen, but, as it turned out in mid-February 2007, not often enough. It was Bert Meijer who pointed out to me that the coaster of the day was the “Quo Vadis”, also known in the offshore radio world as the MV Manor Park. My thoughts immediately turned to a few radio friends with whom I was in contact and sometimes reminisced with, often over a pint: Chris Cortez and Peter Moore. When I saw the photos posted on the coaster site and asked the administrator for more information about the coaster in question, I was sold. I had to dig up a story that I had previously published as a chapter in the book “History of the offshore radio stations 1974-1992, more failures and thumb suckers”, published by the Media Communication Foundation in Amsterdam in 1994.

Towards the end of Gerard van Dam’s umpteenth attempt to get the Radio Delmare project off the ground (1979), there was also talk of involving a number of Britons in this project. In reality, it boiled down to one Brit, Paul Graham, coming on board. His task was to start programme tapes for the Dutch service and to carry out maintenance work. Gerard van Dam, the big man behind Delmare, had promised that the British would run their own English-language service in the future, under the name “Radio Atlantis”. However, fate struck when Radio Delmare was once again hampered by organisational problems and only one crew member remained on board: Johan Rood. Without food or drink, he too eventually decided to surrender, which was yet another victory for the authorities over the Delmare clan.

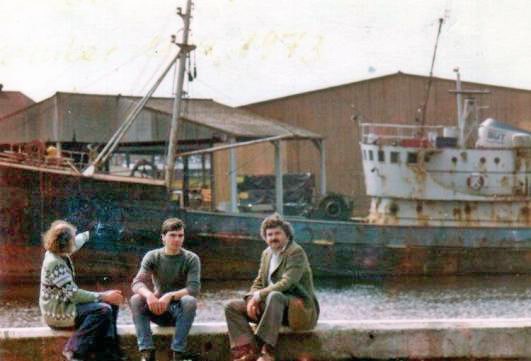

Together with a number of friends, Chris Cortez had closely followed all the developments surrounding Radio Caroline in the late 1970s and was convinced that there would definitely be room for a second station, which should focus on the British listening audience. Long before the MV Manor Park was tracked down, they already had access to both an AM and SW transmitter, each with a power of 1 kW. They also had an option on a Philips transmitter with a power of 10 kW. This transmitter had only been in use for 18 months and was for sale for just £7,500. The MV Manor Park may have been very rusty in appearance, but according to the initiators, it seemed very suitable as a radio ship as it had a double hull and, moreover, a very good water ballast system. Technically, the ship had been written off by an insurance company, so it could no longer be used for its original purpose as a cargo ship.

During transport, a large load of grain had shifted and caused such damage that even the bridge on the ship was damaged. After the radio project failed, the initiators stated that they had reservations about the insurance settlement, as the damage was considerably less than stated in the insurance papers and could therefore be considered insurance fraud. However, a very good deal was struck with the ship owner, through a broker, whereby the people behind the project would be given plenty of time to convert the ship into a broadcasting vessel. Only then would the payment of the purchase price be discussed.

This was very convenient, partly because the people involved had to work with a limited budget and potential advertisers only wanted to put money on the table after it had been proven that the radio station would actually be on the air. Chris invited two other friends to come and take a look at the ship and consider joining the project. These two friends, Kevin Turner and Stuart Clark, would both later work for the VOP as well for Radio Caroline. Stuart’s first impression of the MV Manor Park: “When I saw the ship for the first time, I noticed many similarities with the MEBO II and, very importantly, it was in excellent condition. The plan was to use the large hold below deck to build the studios and to work with a horizontal antenna, the so-called T-antenna system, as Radio Veronica had used in the past.

We were keen to be involved in the project from the outset. Our tasks consisted of completely cleaning the ship and assisting with its conversion into a broadcasting ship. One of the local sailors told us such shocking stories about how he had sailed and manipulated ships in the past that we decided to ask him to make sure we were offshore for Christmas 1979. An anchorage position had already been chosen in Knock Deep, not far from the former anchorage of the MV Mi Amigo. The generators on board also underwent a major overhaul but turned out to be in very poor condition. As a result, we had no light, no heating and no hot water for much of our stay in Sunderland. The toilet flushes were also not working. The cooking utensils were slightly better, although it can be assumed that this was minimal. Actually, it didn’t bother us because we just wanted the project to start as soon as possible.”

The first thing they did was clean the large cargo area. Part of it was covered in a large puddle of water mixed with oil. Bucket by bucket, this filthy mess had to be removed. Kevin Turner: “The most horrible job you can imagine. From top to bottom, you ended up covered in oil, and since we could only take cold showers, it took weeks for that dirty layer, and therefore the smell, to disappear. Then we had to remove this layer from the entire inner skin of the ship, which was covered with a silvery coat of paint. Using gas burners and scrapers, it took us all 14 days to complete this task, after which a red coat of paint would be applied. One of the “freaks” present was Brian, who managed to get the generator working. We were able to enjoy this form of power supply for exactly 24 hours. It was on that same day that we went to play “neighbourhood” at one of the imposed ships, where we took a gangway with us. It was immediately painted silver to prevent anyone from noticing the theft.”

A large caravan was placed in the hold with a crane so that preparations could be made to convert this caravan into a studio. Before that could happen, it was decided to anchor the caravan first so that it would no longer slide around in the hold. The caravan was, of course, an excellent idea, as it would allow for minimal RF interference from the transmitters. The only disadvantage was the lack of natural light, which the initiators did not consider important. Stuart Clark: “The living conditions seemed normal. There were seven cabins with room for a total of 20 people. The wheelhouse, galley, captain’s quarters, etc. all looked clean, although some repairs were needed here and there.”

“When I compare it to the condition of the Communicator and the Ross Revenge in the mid-1980s, I can conclude that the Manor Park could easily have competed with both ships. While we were working hard to equip the ship, Chris was busy trying to attract potential investors. Someone was even sent to the US to approach a number of multinationals. The responses were positive, but the advertisers only wanted to work with us if we were on the air. The reason for this was the bad experiences some had had with the financing of other former offshore radio projects.”

The advertisers’ refusal to invest in the project during the construction period proved to be the final blow, as all the money saved by the members of the group of initiators had been spent and there was no money left to continue. A security guard was put on board by the initiators, which would ultimately lead to the final failure. The owner of the ship had also become very impatient and demanded that the station go on air as soon as possible, otherwise the purchase of the ship would have to be forgotten. The reason for this demand was that the owner had noticed that the security guard was repeatedly taking goods from the ship and reselling them, even though these goods did not belong to the security guard. However, it was not possible to comply with the owner’s demand, and it was decided to remove the equipment that had already been installed from the ship.

Within the free radio world, the necessary reports about the project had already appeared, and especially in England, people went wild when reports appeared that the Manor Park had suddenly turned up in the port of Colchester. It turned out that the entire Radio Free England/Radio Ventura project had come to an end due to a lack of the necessary finances. In Colchester, however, fans were disappointed as the Manor Park had been sold to a new owner. The person in question was Andy Anderson, a name that was familiar in the offshore radio world as it was also used by one of the former technicians of Atlantis. However, the two people were not connected, and the new owner of the MV Manor Park had completely different intentions: to use the ship as a cargo ship in European waters.

However, in 1981, he sold the ship because he could make a huge profit. He had purchased the ship in Sunderland for £25,000, and less than a year later, a number of Italian financiers paid £60,000 for it and had it converted into a sailing school. I am pleased to report that it was a 492-ton coaster built in the province of Groningen. The ship was built in 1956 at the Gebr. Coops NV shipyard in Hoogezand and had a length of 51.97 metres and a width of 8.49 metres. With a maximum speed of 9 knots, the ship sailed under the name Quo Vadis until 1978, before being renamed MV Manor Park.

Hans Knot 2025