By Hans Knot

Graham Gill, born in 1936 in Melbourne, Australia, worked during the 1960s for offshore stations such as Britain Radio and Radio England, broadcasting from the ship Laissez Faire. In the 1970s, Graham was on air with Radio Northsea International (RNI) and Radio Caroline. After 1974, he joined Radio Netherlands. Hans Knot collaborated with Graham on a book about his life and career in radio. In addition, Hans regularly published documents that were not included in the book.

In the year 2010, I have worked very closely with Graham Gill to produce a book about his life and radio career. So let’s return to the memoirs that I wrote – in parallel during the production of the book – in numerous issues of the Hans Knot International Radio Report. Graham’s book has been enriched with a wealth of photos, no less than 40 of which have never been published before. The book can be downloaded as a gift – 15 years after publication – at the end of this article.

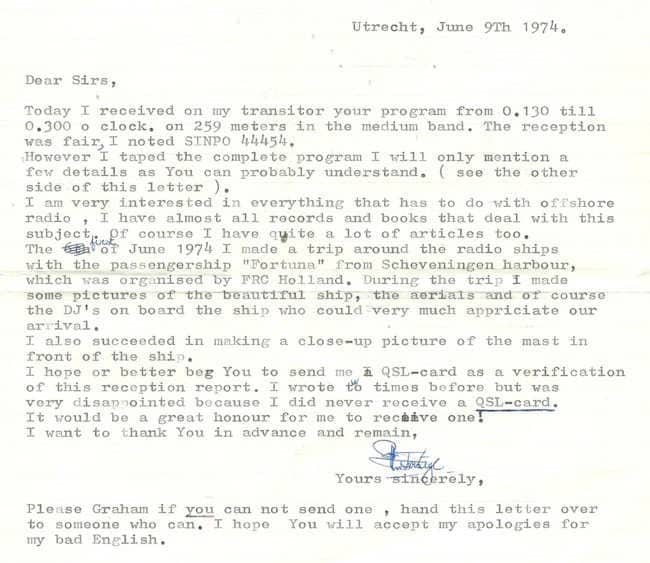

When we were about to begin another two days of work, Graham brought along a plastic bag filled with various notes, letters from listeners, and other radio-related items. From time to time, I published some of the material that were not included in the book. First up is a reception report that was sent from Sweden, describing the reception of Radio Caroline.

I also found a Radio Caroline QSL card I’d never seen before and believe was never officially issued. There were several of them, kept in blank envelopes. On the reverse was a note in which the name of Bob Noakes had even been misspelled.

Among the items Graham brought with him was also a large number of letters from listeners. Many of these were typical request letters, addressed to the postbox addresses of RNI and Radio Caroline in Hilversum. Graham worked for both stations in the early 1970s—during a time when there was still no anti-pirate radio legislation, meaning listeners could contact him entirely legally. Even later, when Graham was with Radio Netherlands Worldwide, most listener correspondence still made its way to Hilversum, where the broadcaster had—and still has—its studios and one of its main postboxes.

However, some listeners took alternative approaches to try to reach DJs on board the broadcasting ship. One such case involved a girl named Karin and her sister Diana.

Graham first appeared on an offshore station in 1966. He delighted listeners across various stations and gained a loyal following—especially among female fans in the UK. He received piles of letters, especially during his stints at Radio Caroline and RNI in the 1970s. Some letters even contained invitations from married women for secret liaisons—complete with strawberries, shared beds, and more. These kinds of notes were quite common in the mail Graham recently brought with him to Groningen, all of which had been stored in his Amsterdam basement for decades.

Here’s a look at one such letter, written in March 1973 in Orpington, Kent.

It was from a listener who had rediscovered Graham on the radio after having heard him on other stations in the 1960s. The writer, a man named Frank, said he had just listened to the Graham Gill Show on RNI on a Saturday evening between 8 and 10 o’clock:

“I must say to you: ‘Welcome back’ to the world of offshore radio, which you said goodbye to, back in 1967. Since then, I’ve only heard your name mentioned occasionally on air, usually through the ‘hellos’ Tony Allan would send out to you on RNI. Occasionally, I also spotted your name in Breakthrough Magazine by Mike Leonard, though that magazine has not been around since August 1970.

I believe you’re originally from Australia and that you’re now permanently living in the Netherlands, having been effectively forced out of the UK due to the MOA. At the end of your programme tonight, I found myself thinking back to your time on Radio England, especially when you played ‘Yeh Yeh’ by Georgie Fame. I still have around ten hours of recordings from Swinging Radio England in my collection. Unfortunately, I don’t have any tapes of your own shows from that time, though your name does come up in others—for example, in Larry Dean’s programmes. As an old fan of Swinging Radio England, I’d love to get hold of recordings of all the former ‘Boss Jocks’ from that station. I’d be honoured if you could help me track some of those down—they would, of course, be strictly for private listening.

I’m also including several International Reply Coupons so you can respond to the following questions:

- Date of the first test transmission on 355 metres

- Likewise, the date of the first full broadcast on 227 metres

- Date of the final Swinging Radio England transmissions in November 1966 (I have the farewell recorded, but no date)

- Date of the first Radio Dolfijn broadcast on 227 metres

- When did you join Swinging Radio England and when did you leave?

- The current addresses of John Ross Barnard and Brian Tilney

I hope you don’t mind all these questions and that you’ll find the time to answer. And if you happen to be on the ship on Sunday the 25th or Monday the 26th, please play a request for Peter Lenton in Kettering, Northants, and for Dave Rodgers in South Molton, Devon. I wish you the best of luck with your future at RNI.”

Just a Letter from a Treasured Collection

Just one letter from the rich collection of correspondence that has been carefully preserved. A seasoned enthusiast might already be thinking: most of these questions could nowadays be easily answered with a quick search online. It’s wonderful to see familiar names reappear in the letters, such as Peter Lenton—later featured in a Radio Caroline commercial for his record shop—and Dave Rogers, who previously worked at RNI and went on to have a long and varied career. It’s worth noting that it was virtually impossible for the DJs aboard the MEBO II to answer all the mail they received, and this particular letter still had its International Reply Coupons attached.

Hundreds of letters have been sorted, with the most remarkable ones stored in a shoebox. From time to time, one or more were selected and highlighted in this recurring feature. These memories are not included in Graham’s book Way Back Home: The Graham Gill Story. Think of these stories as a little bonus, something extra beside the book.

From Flanders

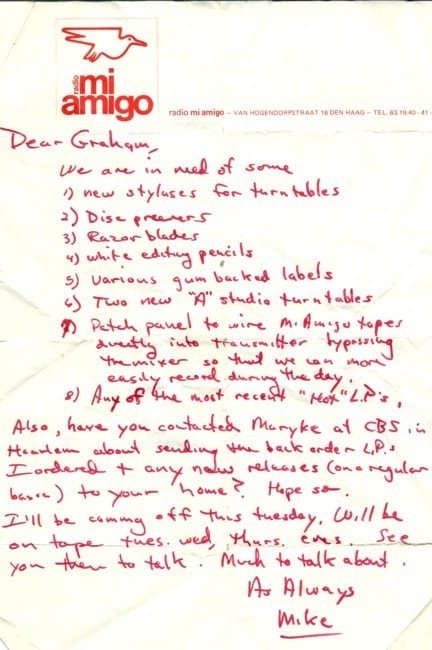

This time, we shine a light on two letters Graham received from one of his colleagues, A.J. Beirens, who was living in Zeebrugge at the time. Writing on 10 July 1973, he said:

“Listen to the DX programme on 15 July, as I’ll be playing a record for you and for Allen. In the ‘World in Action’ segment, a request will be played for Marc van Amstel and Floor. By the way, if you’re the one starting the programmes this Sunday, please note that ‘World in Action’ begins with the 10 o’clock GMT time signal, not a jingle as you’re used to. So start the programme five seconds before the top of the hour. I had a phone call with Andy (Archer) today, and he’s once again feeling optimistic about the future of Radio Caroline.”

This was around the time that Radio Caroline had resumed a full English-language service in June 1973 and launched a second station with a more middle-of-the-road music format. A.J. ended the letter with:

“Give my regards to the lads on the ship, especially Brian.” Naturally, he meant Brian “The Kilt” McKenzie.

I also came across a second letter, dated 18 November 1973, written on the official letterhead of Radio Nordsee International’s headquarters in Zurich, Switzerland. In it, A.J. wrote:

“Hello Graham, I hope all is well with you—both health-wise and professionally. Yesterday, for the first time since my illness, I managed to go outside again, and I truly enjoyed it. I have a favour to ask. In 1973, I’ve spent over £700 on my programme, most of it on reel-to-reel tapes. Could you please send me back around sixty of them to my address in Zeebrugge?”

Christmas 1973

“Perhaps the Trip Tender crew could help, or maybe you and Marc van Amstel could post a few each week. Naturally, I’ll cover all expenses. I’d also appreciate it if you could find out why my programmes weren’t broadcast for two Sundays in a row. Give me a call once you’re off the ship. I might come aboard the MEBO II myself for a few days over Christmas. Will you be on board too? Please ring and let me know.”

Finally, I’d like to touch on the listeners in the Eastern Bloc—particularly one in East Germany. When RNI was also broadcasting on shortwave, and the medium wave conditions were favourable, the station built up a respectable following in those countries. In May 1973, when the RNI double LP was released and promoted across both the Dutch and International services, orders came in via the Groningen PO Box. One request came from the Soviet Union, along with numerous letters from listeners seeking a QSL card.

Officially Forbidden

Tuning into Western broadcasts was officially prohibited, although in many cases it was tolerated. However, those working in the military, customs, or police could face serious consequences, including dismissal. Occasionally, RNI also received letters from the East. In Graham Gill’s collection was one sent from Sömmerda, clearly a reception report. Judging by the illustration, it was from a DX enthusiast listening on medium wave using a 20-metre long wire antenna. Of particular note is the mention that no jamming signal was active at the time—likely referring to deliberate interference from East Germany targeting Western signals.

Three Press Clippings

Another Bomb Scare

The second clipping is a cartoon from a British newspaper dated May or June 1971. It depicts a lit match, implying that if it had gone off, the era of offshore radio stations could have ended far earlier.

Kenny and Cash

The third clipping features letters from the ‘Feedback’ column of an unidentified British newspaper, likely dating from autumn 1973. One letter, signed by six students from Guildford, expressed dissatisfaction with the new Capital Radio show hosted by Kenny Everett and Dave Cash. The station had gone live on 16 October 1973, a week after the launch of LBC.

A Fiasco

The students wrote:

“May we use this column to make a plea for our favourite DJ, Dave Cash? It’s disheartening to see the ‘Kenny and Cash Show’ devolve into a ‘Kenny Everett Fiasco’, with Kenny dominating the programme and Dave left with little more than announcing the time. Dave is a fantastic DJ and deserves better. Please give him his own afternoon slot where he can truly shine.”

In the end, the duo did find their rhythm again in a much more energetic show.

Back and Forth

Many listeners in 1973 were growing weary of the turmoil surrounding Radio Caroline. A clipping from Graham’s archive confirms the year began turbulently, with the Mi Amigo being towed back out to sea from IJmuiden. Dissatisfied crew members, unpaid for their services, had taken control and brought the ship into port just before the new year. Caroline cautiously returned with both Dutch and English programming but soon went silent again. Veronica stepped in temporarily after their own ship ran aground at Scheveningen on 2 April.

Thanks to Others

With new equipment and a generator, Caroline resumed broadcasts with two services in June. However, by July, Flemish money was again needed—this time via Radio Atlantis. Later in the year, Mi Amigo was rescued by another Flemish partner. Despite a strong relaunch, criticism quickly followed regarding dull programming and lacklustre presentation. Andy Archer admitted the team was exhausted. One letter to a British paper around Christmas 1973 carried the stark headline “Lifeless.”

Strong Words

According to writer John Hogg:

“I don’t believe any offshore radio station has ever sounded so lifeless. Some presenters sound like they’re reading every word off a script. They’re so frustrated with their delivery they often resort to non-stop music. If Mr Archer claims they’re tired, it’s time to bring in fresh talent—people with personality, humour, and energy. The music is growing repetitive. Targeting such a narrow audience is financial suicide.”

Money Sent for Nothing

Hogg also mentioned another frustration shared by many in early 1973. Caroline’s Request Show had encouraged listeners to join the Caroline Club. For a set fee, members were promised a card, a poster, and exclusive merchandise offers. Hundreds—if not thousands—sent money to Caroline’s offices in Scheveningen and later The Hague, only to receive nothing.

“People might still support Caroline and Ronan O’Rahilly,” Hogg wrote, “if they hadn’t been deceived. And why haven’t we heard why broadcasts on 389 metres never resumed? All the former DJs from that frequency have found jobs elsewhere. So who’s fooling whom, Mr Archer? Isn’t it time to bring fresh new talent aboard the Mi Amigo?

Judge Dread

Around Christmas 1973, Graham also received a festive card via the RNI postbox in Hilversum. The sender? Judge Dread—known for hits like Big Six, Big Seven, and other reggae-influenced songs, and for his memorable “Big Thank You” jingle recorded for RNI.

Terry in Westcliff-on-Sea

Over the years, in my quest to track down individuals significant to the world of offshore radio, I have visited many towns and villages. One such trip took me by train from London to a small coastal town, nestled under the shadow of Southend-on-Sea in the English county of Kent. It was there, in 1986, that I met Roy Bates and his wife to finalise the book “De Droom van Sealand” (The Dream of Sealand).

Westcliff-on-Sea is a small, but very quaint and peaceful village. From the extensive archive of listener correspondence belonging to Graham Gill, it emerged that RNI also had loyal fans in Westcliff-on-Sea. One of them was Terry — loyal, yet discontented at the same time.

Terry had written to Graham Gill to say he had joined the Graham Gill Fan Club, founded by Pam Wood. But dissatisfaction crept in when Terry mentioned that he had still not received a QSL card from RNI, despite sending in a reception report. Nor had he received the requested stickers and photographs, even though he had enclosed no fewer than four International Reply Coupons.

Nevertheless, Terry’s letter regained a tone of satisfaction when he stated: “I love RNI, and that’s why I also attended a demonstration in support of RNI.” He concluded his undated letter with the heartfelt: “RNI for ever, I love RNI.”

Among the many letters retrieved from Graham Gill’s basement archive, several had travelled great distances before arriving in PO Box 117 in Hilversum. One such example came from the island of Madagascar, off the East African coast.

On that island was one of the relay stations for Radio Netherlands Worldwide. From there, thanks to shortwave reception, they also tuned into the sounds of Radio Northsea International.

The letter came from an employee of Radio Netherlands Worldwide, who wondered whether there were any ties between the addressees — Brian McKenzie and Graham Gill — and Radio Netherlands. Two images of the envelope sent by Barend de Boer are included with the letter.

A Letter from Dordrecht

Among the many letters retrieved from Graham Gill’s archive, I also came across one from Hans van Achterberg, from Dordrecht. He wrote of his keen interest in radio stations and how he sometimes wrote to them for more information:

“The problem is that I often don’t know the addresses of the stations, which makes it difficult. I read an interview with you in PRN and have enclosed some IRCs in the hope of a reply. My question is whether you could provide the addresses of the radio stations you’ve worked for.”

Addresses

Regarding the European stations Graham had previously worked for, it wouldn’t have been useful to list them — after all, Radio London, Radio 390, and Swinging Radio England/Britain Radio had long since ceased operations.

Still, it was fun to read — so many decades later — that Hans had read the interview in PRN (Pirate Radio News). It had been published in 1973, after I met Graham for the magazine, when he had voiced the English commercial for the RNI LP. That meeting also marked the first time I met Graham.

Burt Bacharach

Hans also asked Graham to play a few jingles for his RNI friends:

“I think it was made by Mark Wesley. Dababdap RNI dababdap dababdap dababdap RNI. I think that jingle is just brilliant.”

Hans was, of course, referring to South American Getaway by Burt Bacharach in the RNI version voiced by Mark Wesley. He ended his letter by pleading with Graham to keep working for RNI, saying: “RNI really is the voice of Europe and the sound of the world.”

Leon Russell

Sometimes letters came in from people who were clearly in a, shall we say, altered state while listening to the radio — freely writing down whatever came to mind.

One such example came while Graham was working at Radio Caroline. A listener named Jaime wrote from a small town in Cornwall:

“Hello Graham, and thank you for reading my letter a while back. Unfortunately, due to the ghosting in the airwaves, I can only listen to Radio Caroline from half past midnight until half past four in the morning. It’s all about the conditions.”

“I just got a letter from a wicked chick named Eva. She told me my letter had been read out, heard my address, and started writing to me. Please say hi to her for me, and also greetings to everyone aboard the radio ship — Tony, Andy Archer, Peter Chicago, and the captain. Could you play a track for all my brothers and sisters out there? The song is Everybody I Love You by Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young.”

“I know you get a lot of letters, so no worries if you don’t reply. That’s cool for me! And thanks to everyone aboard for the lovely music.”

“After you mentioned my address, I even got a letter from a guy in prison in Maidstone, Kent. He’s really into Leon Russell. Let him know I’ll be writing him a long letter soon.”

In Conclusion

This recollection clearly shows how radio programmes, particularly on RNI, sparked all kinds of connections. Whether it was through fan magazines or by sharing addresses on-air, listeners found each other.

Politically Aware at a Young Age

The next memory takes us to 6 February 1974, when a 14-year-old David Jennings wrote a letter to Graham.

He said he often tuned in to Graham’s show aboard the MEBO II and added:

“I’m very interested in Free Radio and think it’s terrible that the British government shut down Radio London and other stations. As far as I can see, those stations never caused any harm and brought musical joy to many.”

“After reading a book about the offshore stations, I found out that you worked for five different ones: RNI (of course), England, London, Radio 390, and the excellent Radio Caroline.”

David then had a remarkably good idea for someone his age:

“I think it would be great if you dedicated one evening to playing shows you once did on those earlier stations. I believe some material still exists. That way, listeners can compare the sound of Swinging Radio England with RNI and see how Free Radio has evolved over the years.”

“As you can see, I’ve included a stamped addressed envelope and would like some station stickers. I’ll put them on my bedroom window — much to my mum’s annoyance!”

Reading

David kept up with radio developments by reading Record and Radio Mirror:

“Recently there was an article about public enemy number one, Harry van Doorn. Apparently, he’s soon to decide to outlaw your station and others. Personally, I don’t think that will ever happen. RNI has weathered all sorts of chaos — drifting at sea, a bombing, and more — and I can’t see why it wouldn’t survive any legislation.”

“I also re-read an old Radio and Record Mirror from June 1971. It said that RNI and Veronica, the only two offshore stations at the time, would have to leave the airwaves within nine months due to a new law. As we know, that never came to pass. And I don’t believe Harry van Doorn will succeed either. All the best!”

Sadly, David didn’t get his wish, as the law was enacted in September 1974, and RNI went off air. One wonders what station he turned to next. Unfortunately, David’s address isn’t in the archive, so that question remains unanswered.

Bad Weather

In 1974, especially during the summer, trips were frequently organised to the three radio ships anchored off the coast of Scheveningen: the Norderney, the Mi Amigo, and the MEBO II. These outings were arranged by Hans and Wouter Verbaan of the Free Radio Campaign Holland and by Rob Olthof, before the founding of Stichting Media Communicatie.

Hundreds of fans from various countries were able to see the ships up close this way. There was also a fair chance, if you knew who to ask, of joining a tender run — a supply trip — by the Caroline organisation. That meant experiencing a proper resupply run and maybe even setting foot on the ship.

Sometimes, though, passengers had to be disappointed — for instance, due to bad weather.

On 16 July 1974, Wolf Brundtke wrote a letter to Graham:

“It’s a pity I couldn’t come aboard today due to rough seas. I had planned to have a look around the good old Mi Amigo. Hopefully, I’ll get another chance soon. Still, I want to send my greetings to everyone onboard so they don’t feel so lonely out there.”

He also requested a song for his parents, hoping it could be played that same evening (between 10 and 11pm).

Presumably, Wolf delivered the letter to the tender company supplying the Mi Amigo, because it did indeed reach Graham Gill.

Whether the song was played that night is unknown.

Full Circle

The letter Wolf wrote in July 1974 was scanned two days later and emailed to him. His reply came quickly — by Sunday afternoon — and he shared what really happened back then:

“It’s a huge surprise to get that letter back after all these years. I actually wrote it while aboard the tender, en route to the Mi Amigo. But the seas were too rough to board, so we stayed on the tender.”

“Supplies were placed in plastic containers and hauled over to the ‘old lady’ by rope. That’s how the letter, tucked between reels of tape, made it aboard. Yes, those were still the large reels used to record the Mi Amigo shows. Peter van Dam took the letter and placed it between the tapes. So many memories are flooding back! I’ll look for the photos.”

“I can add that I recorded the Graham Gill Show that evening, during which he read my letter aloud. I’ll make an MP3 of it.”

“Thank you so much for sending the letter back. I always assumed such things were thrown overboard after being read out. So thanks also to Graham for keeping those listener treasures safe.”

“I should also mention that I’m in touch with Graham. Last year, while returning from Paris, he stayed with us for a few days in Berlin.”

A slightly different ending than we expected from a letter written in July 1974 — but all the more touching for it.

From London

On 26 April 1974, a certain Geg Hopkins from London (he noted that his name should be pronounced “egg”) wrote a lengthy letter confessing his addiction to RNI’s broadcasts. He addressed the letter to Graham Gill, who kept it for decades in his cellar, alongside hundreds of others. This autumn, the book Way Back Home: The Graham Gill Story will be published. Ahead of its release, Hans Knot has been delving into Graham’s letter archive to unearth stories that won’t appear in the book.

He Admitted He Was Mad

Hailing from East Ham, Geg began his letter by admitting that it was quite mad to write to a complete stranger. But he also said he knew that people on the broadcasting ship loved receiving letters—it boosted the DJs’ egos. Besides, when post was scarce, even a single letter reassured them that at least someone was still listening. Quite a few statements in a single opening sentence!

Still, Geg had a genuine reason to write. He confessed: “I’m addicted to ‘Radio Two Two Zero’ and rarely listen to other stations—only when it’s absolutely necessary, like for the news. And I understand Dutch well enough to figure out things like the date, time, weather, news headlines and song titles. So really, I’ve no excuse not to listen to RNI. Offshore radio holds a special place in my heart.” He even hinted at a previous involvement with offshore stations—more on that later.

A Good Understanding of Dutch

Though Geg claimed a fair grasp of Dutch, his next line betrayed some gaps: “I think the Dutch language is perfect for radio DJs. Tonny Berrick and Freddy Marks (Tony Berk and Ferry Maat) are really good, I think.” He then explained another reason for writing. He’d heard Graham Gill mention in a broadcast a supposed RNI DJ, to which Graham had reacted on air: “It’s a load of bollocks.” It wasn’t unusual back then for people to falsely claim they were DJs for offshore stations—more fantasy than fact. But was this also the case with ‘Michael Christian’?

Geg Knew More

“What complete rubbish. Michael Christian does not work for RNI and never will. But he definitely was a DJ on Radio Caroline—I think in 1969, during the election period when RNI changed its name to Caroline.” A string of errors, of course—Michael Christian never appeared on Caroline’s roster, and the name change occurred in 1970, not 1969. Geg’s deeper connection to the offshore world then emerged: “I was involved in the campaign for free radio, the whole bus tour thing with Simon Dee and Ronan O’Rahilly. Mi Amigo had been seized at the time, and no one had any interest in buying the ship.”

Lack of Clarity

By the halfway point of the typed letter, Geg’s jumble of names and events became increasingly muddled. But then he wrote: “Michael’s real name is Lyndsay Read (Reid), currently a label manager at Purple Records. He occasionally presents a show on Radio Caroline.” It was clear he meant Michael Lindsay, who had indeed worked aboard the MEBO II and briefly presented shows on Caroline in 1973 during the “389” period. One can imagine Graham simply couldn’t follow the thread.

He Knew It Too

Geg may have realised this himself, as halfway through he admitted: “I might be talking complete nonsense. That’s probably because I’ve been away from radio for a while, and I’ve gotten it all muddled. If so, I apologise.” He went further: “Lindsay was my manager for a while, until about a year ago. I’m a DJ myself—or was, I should say. I hope to be again soon. So yes, I know Michael Lindsay as well as I know my own sister.”

A Harsh Judgement

Incredibly, Geg went on to give a scathing review of Lindsay: “I think he’s about as competent as shite, but I like him anyway. He never made a good DJ. We worked together on various shows in London and along the South-East coast until he set up his own firm and I ended up working for him.”

A Failed Attempt at Caroline

Geg also mentioned that Lindsay had tried to get him onto Radio Caroline the year before: “Unfortunately, there were serious technical issues aboard the Mi Amigo. I decided I needed a backup plan, so I went back to university. DJing in clubs had also become less appealing—too much violence. I’m a big, strong guy, but I’ve stepped back from it all to avoid getting too caught up in that world.”

Technical Training

He had studied radio engineering at university and in 1974 hoped to return to it in order to carve out a career in broadcasting. But he acknowledged that it would become harder to break into offshore radio, especially with the Dutch government set to shut the stations down later that year. Caroline was also too disorganised to be a serious option. At 23, Geg had already travelled widely, including a stint in Australia—Graham’s birthplace. He returned to his view on DJs.

An Honest Admission

“I think you’ll agree,” Geg wrote, “that most of these guys aren’t exactly brilliant—they’re just egotists. Personally, I’m glad to be grounded. Although praising oneself isn’t advisable, I think I’m brilliant. Sadly, these DJs won’t lift a finger unless you first shine their shoes. I tend to steer clear of them. I know a lot about them, but I try to stay on good terms.”

Tuning in to Foreign Languages

He added: “I didn’t write this letter to be read on air, but feel free to quote bits if you like. I think most Brits won’t listen to RNI’s Dutch service simply because it’s in Dutch—they can’t stand foreign languages. I’ve noticed the English and Dutch services play different records. Some of the foreign (well, to the English ear) records are outstanding. It’s a shame we don’t hear more of them on the English service, especially considering 95% of Dutch people speak excellent English (and French and German too). If I had my own show, I’d play loads of Continental records—if the format allowed.”

Signing Off

Geg signed off by asking Graham to dedicate a song to his landlord and apologised for typing the letter rather than handwriting it—though the apology itself was written by hand. Reading and rereading the letter, it’s hard to shake the feeling that Geg was hinting at something more—that perhaps he was hoping to be invited aboard the MEBO II. I decided to investigate whether this uniquely named letter-writer could be tracked down online, using his name and the keyword “radio.”

Successful Search

It didn’t take long to find a blog authored by a Geg Hopkins. I contacted him to ask if he was the same man who, back in the 1970s, had written to Graham Gill and had ties to Michael Lindsay and RNI. I also mentioned that I was working through Graham Gill’s archive.

Far Away Now

Within the hour, I received a reply:

“Come on Hans, you’re pulling my leg! Yes, I’m the same person—and I probably did write that letter to Graham Gill. From what I’ve heard, he was a level-headed chap. Back then, I tried everything to land a job on a radio ship. I came close a few times—not because I wasn’t good enough, just unlucky. It became a big part of my life story. I really gave it everything. I was obsessed with those stations. I was still very young and often tell the story of Mike Lindsay to this day. Where is he now? He always looked sharp and was well educated.”

Contact with Ronan

Even in 2010, Geg clearly remembered a lot:

“Lindsay spoke with Ronan and others, trying to get me a slot on Caroline. I had even found a sponsor through the London Rubber Company—not direct funding, but promises. They made Durex condoms, among other things. I almost made it to the ship before the Dutch government stepped in. I used to write long letters in those days. Big mistake. Now I write long blogs—don’t all DJs?”

The email was sent from Admaze Media, based in Bahrain—one of the Gulf States.

Purple Records

In his email, Geg shared many memories. He still thinks of Mike Lindsay often and hopes to reconnect. He remembered him last working as label manager at Purple Records—around 1973, when Caroline promoted releases like the Colditz soundtrack and Yvonne Elliman. Back then, Geg had long hair and a foot in the music world.

“I can’t recall what was in the letter I wrote Graham, but your email brought it all flooding back. It’s amazing the letter resurfaced. I still have old show scripts and listener letters from 30 years ago—so yes, we must all be a bit mad.”

Never Met

Geg never met Graham Gill in person, but heard he’d been retired for some years. Still, he had a strong opinion:

“Old radio men don’t retire. Look at Alan Freeman—he kept going till he couldn’t. Funny thing, I just mentioned Graham’s name the other day to one of my investors—someone who sadly has little appreciation for good radio. I told him about Graham’s singing, especially his version of Way Back Home.”

He added that he’s still involved in radio and, with investors, hopes to acquire several English-language stations. Fortunately, he now has a digital copy of his 1974 letter—just in case he finds time to keep dreaming of the offshore days.

The Lost Demo Tape

Now, we move briefly to 1969. On 27 May of that year, I found a letter in Graham’s archive addressed to Mrs Pam Wood, later identified as secretary of the Graham Gill Fan Club. The letter was written by David Dore, assistant to the BBC’s Light Entertainment Manager.

It showed that after working on offshore radio in the ’60s, Graham tried to land a job with the BBC. Following Radio 390’s closure in 1967, he moved to Amsterdam, working in entertainment before returning to the ships in 1973. Pam’s earlier letter had likely enquired about the status of Graham’s demo tape sent to the BBC.

Whether a second attempt was made remains unclear, even after speaking with Graham.

The Late-Night Listeners

In many letters from listeners unearthed this year from Graham’s cellar, some clearly preferred tuning in during the late-night hours—perhaps after work or due to insomnia. One such listener was Robin Harvey from Halesworth, Suffolk, who wrote in June 1973:

“Dear Graham, thank you for presenting two of the best shows on the radio—your own, and The RNI Request Show. I’m thrilled that you’re now on from midnight to three; those are my prime listening hours. RNI has always been my favourite station—since early 1970, when Morse code and music rang out over 186 metres.”

He asked for a request to be played for a friend and expressed hope of meeting Graham in person that summer during a trip to Scheveningen.

Way Back Home

For many years, the annual Radio Day in Amsterdam was closed with Graham Gill’s modern rendition of Way Back Home, based on the 1972 Motown version by Junior Walker and the All Stars. The instrumental track was used by Graham to sing a welcoming intro to his shows. The song had first been recorded in 1969 in a softer arrangement by The Jazz Crusaders.

In his 15 November 1973 programme, Graham dedicated a song to a loyal listener from Dublin—Jennifer. A few weeks earlier, she had written to ask if he’d heard of the Irish band The Chieftains, suggesting colleagues McKenzie and Don Allen might know them. Surprisingly, she mentioned them in 1973—though they had been founded in 1962, they only broke through internationally in the late 1980s.

Jennifer enclosed a special document: inspired by Graham’s singing, and his regret at not continuing Way Back Home, she had written a Part Two for him. “The lyrics may not be perfect,” she wrote, “but I hope they fit the music.”

There were letters from adoring women and grumbling listeners, but also from individuals keen to wag their finger at the DJs and point out their mistakes. A good example is a letter written by Philip Cox from Chipping Norton. It’s unclear whether he lived there or was merely staying temporarily, as the letter was penned on stationery from The Blue Boar Hotel. He began by expressing his suspicion that the listening post aboard the radio ship might read letters rather hastily, and he also hoped that the sea would be calm to ease the reading process. After some comments and a request for a song dedicated to acquaintances, Philip shifted to a tone of discontent.

“Naturally, you each have something special to offer, and if I were to characterise the current DJ line-up in contemporary terms, I’d summarise it as follows:

Brian McKenzie, for example, repeatedly says ‘Good good record’ or something similar, always followed by the word ‘record’. Then there’s Arnold Layne (who deviates from the rest of the DJ team). In his programme, he always refers to Radio Northsea International by its full name, never just ‘RNI’. Mike Ross repeatedly blunders by referring to ‘Cuddley wifes’ on his show, and Graham Gill’s English comes across poorly when he greets listeners with ‘Hi Thur Good Peepul’ every evening. Then there’s the hollow spirit of yesteryear’s North Sea Radio, Robb Eden, who often gets no further than ‘This is’ and ‘It’s’ – a clear sign of what might be called the ‘Santa Claus Syndrome’.”

Looking back at the letter today, it’s evident that Graham heavily edited Philip’s text, crossing out large sections as unsuitable for broadcast on RNI.

Thankfully, there were also listeners who were thoroughly delighted, like Pieter Herrewijn from The Hague. He had a particular way of tuning in: “I’d like to compliment you on how you present your programme, especially during the early hours of the day. I almost always listen while driving my car – a VW 1303S. Its colour, in case you’re curious about what your listeners drive, is metallic blue. I thoroughly enjoy your shows, particularly because of your many interesting remarks, always delivered in a very relaxed manner. You also always pick the most fitting music. For your information, I’ve become a member of RNI and I expect that Northsea will gain many more members.”

Johnny O’Keefe was indeed popular in Australia. Born in January 1935, he sadly passed away far too young on 6 October 1978. Over a 20-year career, he recorded more than 50 singles, 50 EPs and dozens of LPs. He was the first Australian rock and roll artist to get the opportunity to tour in the United States. From 1959 to 1974, he made it into the Top 40 in his home country no fewer than 29 times.

There were also deeply personal, lengthy letters from listeners, some of whom repeatedly shared their life stories with Graham. He would read out excerpts and respond in kind, with heartfelt messages, particularly to his female audience. This often created a sort of boomerang effect, as regular listeners to Graham Gill’s programmes began to hear familiar names crop up time and again – like Ruth Fernandez, originally from East Africa and now living in England. A strong ‘radio bond’ developed between them, which, in Ruth’s case, may have gone even deeper.

But there were also listeners who offered plenty of advice, like Theo Huttinga from The Hague. He wrote regularly to Graham and praised him in July 1973 for becoming a popular presenter in such a short time. However, Theo also wondered why some of his letters hadn’t been read out – at least not during the listening hours he’d clearly indicated. It was simply too tiring for him to stay up late into the night. He referred to a previous letter in which he had included a photo of his tape recorder. In closing, he advised Graham to start each show – after the first track – by announcing the names of everyone getting a requested song that day. It does leave one wondering – what exactly did Theo need the tape recorder for?

One mustn’t forget that listeners also sought emotional support from the DJs onboard, particularly when they felt dissatisfied with their own appearance – and yes, it was mostly women. One such letter was from a girl named Lindsay, who wrote that she was completely taken with “that beautiful Marie Osmond”. She added that she often wondered why some people were blessed with good looks and others were not. She confessed that she was wholly unhappy with herself: “I have to wash my hair every two days because it gets greasy so quickly. I’ve got four spots even though I always use cleansing lotion. And when I read this letter back, I see that I’ve written it poorly. Apparently, I can’t write well when I’m in a grumble. Plus, I should really be doing my homework.” She ended by saying she expected Graham to write back – she’d enclosed several IRCs to make it easier.

International Reply Coupons (IRCs) were introduced globally to cover return postage from another country. If you wanted information from a foreign company, you’d enclose an IRC to encourage a reply. Likewise, DXers (radio enthusiasts) would send one when submitting reception reports to foreign radio stations – hoping to receive a QSL card in return as confirmation. These days, it’s common practice in many countries to include a US dollar bill instead.

Naturally, there were also countless letters from fans wanting to visit the station or asking how they might get onboard to witness a radio show. Interestingly, such requests were always struck out and never answered on air – just in case a DJ accidentally responded to them during a broadcast. One such request came in a letter dated 12 August 1973, written in Brookwood, Surrey by John Gording. However, the following questions were addressed: “I wonder if you could provide information available about the radio ship and the station? I’d also like to request that your office send me some stickers and posters. Lastly, is the RNI souvenir book still available, and can it be bought in bookshops in England?” John closed by requesting a song and wishing the team all the best, especially good health. It’s assumed that any inquiries about visiting the Mebo II were strictly off-limits for the DJs, which is clear from the fact that John’s questions on this were repeatedly crossed out and left unaddressed.

Schoolteachers, too, were diligent letter writers. One final example from August 1973 comes from Miss Hillary Norris from Northern Ireland. She joyfully described taking a group of 47 teenagers on a three-week trip through the Netherlands, visiting places like Kapelle, Wemeldinge and Schore: “We found the Dutch people very friendly and hospitable. We made many new friends and were truly sad when it was time to leave. Every day we travelled by coach from place to place with the radio blaring. Even though we didn’t understand the DJs, they played such lovely music – songs that we simply don’t hear on the radio in Northern Ireland: Redbone, Bella Italia, Angelina Sex Machine and Do You Love Me, the current number one in Holland. These songs aren’t played on British radio or even Radio Luxembourg. Since discovering RNI in the Netherlands, I’ve tried tuning in back home – I can pick it up after midnight. Sadly, none of the tracks I heard during the day were being played, apart from ‘Do You Love Me’. I’m convinced that if you play more of those daytime songs at night, you’ll gain many more fans. But rest assured, you have me as a lifelong listener now.”

By early July 2010, we’d made enough progress to plan a visit to the printer for the first proof copy. Before heading out, I decided to rummage through Graham’s archive myself. In two old suitcases stored in his basement, there were hundreds – if not thousands – of letters, notes, and memorabilia from his time on the air during the 1960s through to the 1980s.

There was far too much to read properly, and there wasn’t much room to explore the tall stacks. I ended up filling a large boot box and a jumbo shopping bag almost blindly. After our visit to the basement, we headed to the printer to finalise details. Feeling quite satisfied, we then celebrated the occasion over a pint at Maximiliaan, one of Amsterdam’s finest beer cafés.

During those couple of entertaining hours, Graham shared numerous stories from his broadcasting days. At one point, we got onto the subject of favourite beers, and he told us that his all-time favourite was Guinness. He noted that while Ronan O’Rahilly hadn’t always treated his staff particularly well, he did at least ensure there was always plenty of Guinness on board the MV Mi Amigo. A trivial detail, perhaps – until you hear what happened next.

After we left Maximiliaan and headed for the Metro, Graham and I went our separate ways at Amsterdam Central Station. My train to Groningen – which usually passed through Hilversum and Amersfoort – was delayed due to an accident near Hilversum. I quickly learned that I could reach Groningen via Utrecht instead. While waiting the 35 minutes for the train, I sat on a bench and randomly pulled an envelope from my shopping bag.

The letter was from Trevor Larkin, from Tonbridge in Kent. He wrote: “Just a few lines to welcome you to RNI. I hope you’re enjoying yourself – it’s great to hear you back on the air. I really enjoy your shows and the excellent music selection. What do you think about the Dutch government’s plan to introduce legislation against the offshore stations? I can tell you it really upset me. Just the idea that this could bring an end to RNI’s broadcasts is heartbreaking. You bring us so much joy and do no harm.” Later in his letter, dated 3 February 1974, Trevor mentioned a planned trip to Amsterdam that summer: “I’ll bring you some Guinness, since I’ve gathered from your programmes that it’s one of your favourite drinks.”

“The reason you called me groovy had mainly to do with the fact that I requested a song by Slade for my pupils. This time, may I ask you to pass on greetings during the programme to my husband Benjamin, as well as to my sons – Alastair and Denzin. Also, say hello to Tiddle the cat and Old Black Face, the family parrot.”

“May I once again say how much I enjoy the programmes on your station – especially those by Mike Ross and yourself. You speak to your listeners as if they’re personal friends and not like we’re half-wits, as some of the less popular stations do. Please thank everyone who made it possible for RNI to exist, on my behalf. There’s a lot of sentiment when I say that I hope RNI remains on the air for many more years to come.”

Sadly for Norah and many loyal followers of the station, it would be just under seven months before RNI’s frequencies fell silent for good.

Though Graham had said farewell to family and friends in Australia back in 1966, his heart remained tied to his homeland. Occasionally, he would talk about it on air, and over the years he returned several times. He often said he felt like the prodigal son upon returning. The mayor of Griffith – where Graham had lived and worked for years – even invited him for a dinner. At the radio station where he once worked, he was welcomed back to present guest shows.

In The Area News, a local paper in Griffith, there was a piece on 30 March 1977 noting Graham’s temporary return:

“Mr Gilsenan worked at 2RG in Griffith from 1955 to 1965, contributing to a variety of programmes. He has travelled extensively in Europe and is now a DJ for Radio Netherlands, the Dutch World Service. Yet he describes his years in Griffith as the happiest of his life.”

“Now known on air as Graham Gill – because listeners could never spell his surname correctly – he left 2RG to travel across Europe on his way to England. He worked in Switzerland, Austria, Germany, the Netherlands, Italy and Greece. He spent two years working in England, for two so-called offshore radio stations.”

“When the government shut these down, Gilsenan was one of many DJs left unemployed. He moved to Amsterdam and managed a well-known nightclub, meeting many international artists. After touring abroad with Dutch band The Cats, he joined Radio Netherlands in 1975, where he presents a Top 40 show every Saturday night, and is responsible for the request show.”

“Graham: ‘I’m back in Griffith on a sort of pilgrimage – to soak in the nostalgia and see some old faces. I’ll be here until Friday around lunchtime and can be reached on 622984.’”

Clearly, the article didn’t have room to fully detail Graham’s radio adventures in Europe. It failed to mention the many stations he worked for or the key events around RNI and Caroline in the 1970s.

It was in 1974 that RNI left the airwaves for good, marking the end of Graham’s offshore radio career. But the suitcases in his cellar don’t only contain letters from his time at RNI and Caroline – also from his years at Radio Netherlands World Service.

Let’s turn to a letter written on 26 January 1976 by Woody Smith, who lived in Knoxville, Tennessee, USA. He addressed the letter to Graham Gill, then working in Hilversum. Woody had heard Graham on The Happy Station and wrote:

“I’m writing because you were once a DJ on Radio Nordsee International. I listened often to RNI, and as it was my favourite station, you can imagine how frustrated I was when RNI ceased broadcasting on 31 August 1974.”

“Before RNI shut down, I never managed to get a QSL confirmation card. I recorded several parts of programmes during April and May 1974 – mostly from your shows. I have a blank Jackie Nordsee card, and would be grateful if, upon receiving a copy of my recordings, you could fill it in as confirmation of reception in America.”

Woody clearly listened attentively to Graham’s shows and added a little incentive:

“Of course, the tape won’t be entirely filled with RNI material – but I can pad it out with programmes from the 1930s and 1940s, which I know you’re fond of.”

He added he had written four or five times to RNI in Hilversum and had also sent reports to the Swiss office in Zürich:

“I never received a reply – perhaps they were too busy with the preparations for the final broadcasts. I hope your new job at Radio Netherlands is going well and hope to hear from you.”

It was signed simply “Woody”.

I can tell you that Graham never replied – I was the first to read this letter after opening the sealed envelope, 36 years later.

Listeners were often frustrated when their letters went unanswered. They would then write to another DJ and complain about the silence – assuming the staff were all reliable. Take, for example, the letter from Derek Arnot of Dunfermline, Scotland, who wrote in July 1973:

“I’ve been listening to RNI since 1970 and have written many letters – mostly to Dave Rogers. Last November, I also wrote to Don Allen, but never received a reply. I now write to you, hoping for more information about RNI and, perhaps, a QSL card.”

He described how he listened on a valve radio, with an extra antenna to improve reception:

“Often with little interference, getting a SINPO of 3-4, 4-5, and sometimes 5. Usually, I listen between 8 and half past 8 in the morning, a quarter of an hour around midday, and from 7pm till often 2 in the morning.”

Derek knew FM reception of RNI in Scotland was a dream:

“FM reception would be ideal, but it’s impossible up here. I’d like to ask a few questions: What happened to Radio Caroline? They vanished from the airwaves. And what are RNI’s plans if the Dutch government tries to ban offshore stations next year?”

He had circled his song request in red – I assume Graham played the song but did not answer the questions about Caroline.

The next item I pulled from the suitcase was a postcard from Allan Krautwald, a Danish listener, sent in late July 1973:

“I’m currently sitting in the park surrounding the Radio Luxembourg buildings. I just said hello to one of RNI’s former DJs, Mark Wesley, who’s now on 208. Could you play a song for me and all my friends and pen pals on Friday or Saturday night? And could you write back with some news about RNI’s future?”

The card’s image, I must say, was stunning.

Many letters in the archive include requests for technical advice. For instance, Jürgen Beier from Vrailling, near Munich, wrote:

“My name is Jürgen Baier. I live in a small village near Munich. Although RNI reception is mostly poor, I still listen for the music. I want to buy a shortwave radio, but I don’t trust the advice of salespeople. Could you read this letter out – perhaps some DXers could suggest something? I don’t need anything expensive, just something that works well.”

He also wrote: “Is it even legal for Morse code to be broadcast over your frequency? It’s very annoying. By the way, can your programmes also be heard in America?”

Even medium wave listeners quickly noticed Graham’s remarkable voice and asked to make use of it. One special request came from Bob Glen in Bishop Auckland, Co. Durham:

“Dear Mr Gill, I write to you on behalf of the Durham Hospital Radio Network, where I am programme director and DJ. We’d like you to voice a few jingles for us to use. As we are entirely volunteer-run, we can’t offer payment. If you’re willing, I’ll send a tape and script. Keep up the great work at RNI.”

Let’s hope the reader Bob Glen from International Radio Report is the same person – perhaps he can tell us whether those jingles were ever made.

Programmes from RNI and Caroline were popular in Ireland too, with many letters arriving in Hilversum. David Gardiner from Dublin wrote during the period Graham was pre-recording his shows from a record shop in Amsterdam:

“I’m a regular listener to your shows on Caroline and previously on RNI. I thought it time to write and say how much I enjoy your programmes. I hope the North Sea behaves and that you’ve enough Guinness on board – after all, Guinness is Ireland’s best export after Ronan O’Rahilly!”

He added: “I recently visited Yorkshire, though didn’t manage to see Stonehenge. I heard it’s still impressive. I read your life story in Monitor Magazine – fascinating that you worked with Alan Freeman in Australia.”

David closed with: “Though I usually prefer live shows, your pre-recorded ones from Record World in Amsterdam are excellent – it seems to give you more time to do interviews.”

He included an International Reply Coupon, still inside the envelope. The letter appears to have never been answered.

A final letter came from Janika Wigerfelt of Örebro, Sweden, a new listener in 1973:

“I’ve been listening to RNI for a few months now – every evening. I stumbled upon it by accident while looking for Radio Luxembourg, which had been my favourite station for years. I’ve gathered you broadcast from a ship – I’d love to know more about RNI, your work, and the other DJs.”

She asked: “Do you live on the ship too? Could I visit it when I’m next in the Netherlands – or is that not allowed?”

She also enquired about the instrumental music Graham played at the start and end of his show: “Way Back Home” by Junior Walker & the All Stars and “Man of Action” by Les Reed & His Orchestra.

Finally, she wrote: “If you ever come to Sweden, I’d love to meet you and give you a proper tour.”

Others sought more information about how to get started at a radio station. For example, a letter from November 1973 has been preserved, written by a certain Howard Baker from Colchester:

“I’m very impressed with the professionalism you convey together with Brian, Don Allen and others at RNI, and I’d be very grateful if you would listen to the enclosed tape and give me your comments on the content.”

Howard was studying at Essex University at the time and occasionally presented on the campus radio station, but he faced a considerable issue:

“It’s really hard to get an honest assessment of my programmes here. I love radio and hope to enter the industry once I finish my studies. Ideally, I’d like to spend some time working in commercial radio, either in the States or elsewhere. If you have any ideas on how to go about that – given your experience at stations across the world – I’d really appreciate your advice. I look forward to your reply.”

It’s unknown whether Howard Baker ever made a name for himself in radio, though a namesake is known as a BBC radio dramatist. Listeners who frequently tuned in to RNI or Caroline would occasionally hear remarks on air suggesting that being on board wasn’t always a pleasure. Some listeners responded to these hints, such as the message written on the back of a postcard from two distant female fans in the United States.

RNI had listeners all over the world. Here’s an excerpt from a letter dated 14 February 1973, written aboard the MV Challenger while it was docked in Port of Spain, Trinidad. The letter came from Patrick Thomas:

“Dear Graham, I managed to listen to a good portion of your programme while tuning into RNI via the 49-metre shortwave band in Trinidad. I decided to write and ask whether you might mention my name on your show for a few friends. Whenever I’m in Europe, my radio is always tuned to RNI – it’s undoubtedly the best pop station in Europe, and the staff are incredibly warm and personal in handling the incoming mail. I also really enjoy the regular address readings for pen pals.”

After some less relevant content, the letter continued:

“From around 21:30 CET, your station comes in quite clearly here in Trinidad. I’ve no problem at all tuning in via shortwave. I’m a 27-year-old man with French, Scottish, Spanish, Black and Chinese heritage. I’m an electrical engineer and enjoy pop music, photography, global affairs, reading and psychology.”

Official reception reports were also regularly received at the stations, often neatly filled out on log sheets by members of DX clubs. Esko Jukkala, for example, was member number 2415 of the Finnish DX Association and lived in Turku during the 1970s. He sent an official report to RNI.

People tuned in to RNI’s International Service from all kinds of places, not just from home or the beach. Here’s part of a letter from Terry in White Cliff-on-Sea, Essex:

“I currently work nights at a hospital, and the head nurse allows me to listen to RNI. So there I sit, with one earpiece in. Please pass on my best to Brian – I think his rock and roll programme is excellent. I also always try to catch your shows, Graham. I think they’re brilliant. I work every night, which is why I listen to RNI. It’s definitely the best station around. Everyone else at work hates it because they’re BBC fans. I tell them they should leave. I’m a free radio listener – here’s to a long life for RNI!”

One of the earliest demonstrations I recall supporting offshore stations was in 1967 in London. Several more took place in 1970, organised by the Free Radio Association (FRA), mainly in protest against the British government. In one of Graham’s surprise boxes, I found an envelope with no letter, just a copy of a petition that was later sent to the Dutch Embassy in London.

A few days later, I came across a letter dated Sunday 8 July 1973, from Robin Harvey:

“I’m currently listening to the RNI Request Show, which I consider one of the best on RNI. I’m quite alarmed by the plans of the Dutch authorities to introduce a law against offshore stations, especially RNI. I’ve listened to the station nearly every evening since its early days in 1970. Over the years, it’s come to mean a lot to me. I believe the proposed legislation is both unnecessary and unfair. I want RNI to remain on the air for many years, and so I decided to create a petition and send it to the Dutch Embassy as a form of protest.”

He continued: “It’ll show how many people truly care about RNI and don’t want to lose it. Graham, I wonder if you could help by mentioning the petition a few times on your show, saying that people can request a copy from me and return it signed within two to three weeks. They should include a stamped, self-addressed envelope. I’ll enclose a sample petition. I hope you support the message I’m trying to get across. I’ve already collected over 100 signatures in just a few days.”

I realised this must be connected to the earlier envelope containing only the petition – clearly Robin had forgotten to include it the first time and sent it quickly afterwards.

Nearly six years after the closure of Radio 390, where Graham Gill once worked as an announcer and presenter, some still wrote to him about the station. One such letter, dated 15 April 1973, came from Fred Power in Sandown on the Isle of Wight: “Just a short note to say I couldn’t tune into your programme today. The signal was completely absent on the 49-metre band. If you can receive Radio Solent on board, I hope John Piper will play a request for all former Radio 390 staff. No news yet on David Lye regarding the station’s return to air – I’ll keep you posted. Personally, I think a revival is unlikely.”

Graham didn’t recognise the name Fred Power, and considering the mention of David Lye – part of Radio 390’s management – it remains a small mystery.

Next from the box was a letter from a girl in Dublin who mentioned she was starting her letter for the third time, with two previous drafts already sealed. Her name was Genifee, and she sought Graham’s advice on potentially moving to Amsterdam as a foreigner. She desperately wanted to leave Ireland and was hoping to find work as an au pair or in a hotel – so long as she didn’t have to work 12-hour shifts.

“I worked in Belfast for three years, but moved to Dublin because it’s far more peaceful. If it weren’t for the conflict, I’d like to return to Belfast. I don’t know if you meet Irish people visiting Amsterdam, but not all of us are like what’s portrayed on TV. I could go on forever about that. I love politics, especially when people are misunderstood. If I ever get to meet you, I’ll explain in more detail.”

She was clearly going through a tough time:

“I’m a bit of a daydreamer. I’m not running away, but please don’t read this letter out on air. I’ve not told anyone at home that I want to leave Ireland. If someone hears it on the radio or a neighbour passes it on, that could cause problems.”

She apologised for the lengthy letters and confessed that she was extremely shy, only opening up after a few whiskies or vodkas. One of her many letters included a poem.

The letters Graham stored in his cellar came from all corners of the world and spanned his time at RNI, Caroline and Radio Netherlands. One came from the prison in Scheveningen, addressed to “Dear DJ, whoever you are”. The writer, identified only as “LA”, explained:

“You might be interested in my current situation – I’m serving a two-year sentence for bank fraud in Scheveningen prison. So I’m quite close to the MEBO II. My wife and I have this arrangement: we both listen to RNI in the evenings, and it makes us feel connected. I think you’ll know what I mean.”

He requested that Graham play Speak Softly by Andy Williams for his wife, daughter, and four former fellow inmates. He added:

“Obviously I can’t always listen due to strict rules here. But I know I’ll be able to tune in on Sunday the 29th, so please play the record then.”

It’s unknown if the request ever made it aboard in time.

Some letters were even written on hotel stationery, the kind you find on a desk in your room. One such letter came from Philip Cox, who not only enjoyed listening to RNI but also had a passion for jingles. He included a few suggested lines for the DJs to use in their productions.

Even after his RNI and Caroline days, Graham kept in touch with listeners. In 1975, for instance, he received a Christmas card from Pim, an Amsterdammer who had emigrated to America:

“I’ll always love your programmes. I’m originally from Amsterdam, but I’ve moved to the US. Merry Christmas and a prosperous 1976!”

I personally met Graham Gill for the first time in 1973, during the production of the RNI double LP by Jacob Kokje, with myself as co-producer. After pressing, a commercial was made using Graham’s voice for the International Service. The double LP was released on 4 May 1973 on Park, a sublabel of Basart Record Company. So it was a nice surprise to find a letter from Philip Badon in Redditch, England, dated 28 June 1973:

“I recently bought a copy of the ‘History of RNI’ double LP from Pirate Radio News and think it’s excellent.”

Although Graham has lived in the Netherlands for over 43 years, he still speaks English with everyone – even those who write to him in Dutch. However, in November 1973, Astrid Blankensteijn wrote:

“Dear Graham, I think your Dutch is very good. You’ve clearly learned a lot in the months you’ve been with RNI. There are foreigners in this country who don’t speak a word of Dutch – simply because they’re too lazy to learn.”

But not all listeners were happy. Angelika from Lübeck, near the former East German border, wrote back angrily after Graham mistakenly assumed her friend Dagmar was a boy, despite her earlier letter clearly stating it was her female friend:

“I was really annoyed to hear you refer to Dagmar as a boy. It seems like you don’t take listener letters seriously or read them properly.”

Let’s forgive the mistake – we all enjoyed Graham Gill’s shows on RNI and Caroline immensely.

Graham Gill, who beacme 75 years old in 2011, clearly had fond memories of his time on RNI’s MEBO II. One of the first letters I pulled from his archive today was from Terry in West Cliff-on-Sea:

“I’ve had two operations in the past 15 weeks, and thank goodness for RNI – it keeps our spirits up. Without you, we’d feel lost. You’re definitely working at the best station. I’ve got two big photos of RNI above my bed because I love you all so much.”

She also enclosed a second short note with a simple request for her friends Susan Gregory and Ray Anderson from Frinton-on-Sea. That last name rings a bell…

Listeners even corrected the DJs when they made mistakes. These days, we post on forums or send an email, but back then it was all done through letters. For example, Graham Cann from South Croydon wrote on 1 April 1974:

“I listen every week to RNI’s Topper 20 and have kept track of every chart since the Top 30 days. I think you made a few mistakes last week. You opened with ‘Seasons in the Sun’ by Terry Jacks and said it was number 20, but it was actually number 1. Genesis with ‘I Know What I Like’ was at number 20. Just one example.”

Summer of 1974: Letters, Concerns, and the Spirit of Free Radio. In the summer of 1974, many letters from concerned listeners arrived, expressing deep anxiety about the future of stations such as RNI and Caroline. This was in response to the Dutch government’s announcement that it would be introducing anti-pirate radio legislation. Despite the upcoming law, the organisation behind Radio Caroline and Mi Amigo declared that both stations would continue broadcasting. John Biles wrote in to express his happiness that Caroline would survive, even enclosing a drawing to show how supplies could still be delivered after 1 September 1974.

In earlier instalments of this series, I’ve already mentioned that RNI had many long-distance listeners. On 14 January 1974, a listener named Chia requested a song for her friend Chubby. She specifically asked for it to be played after midnight, as that was when it became possible to hear RNI — other stations would have gone off air by then. Her letter came from Ljubljana, now the capital of Slovenia, which at the time was part of Yugoslavia.

Another example of long-distance response is shown in the accompanying image: a reception report from someone who picked up RNI on 23 April 1973, between 20:10 and 20:33 GMT. The listener tuned in to one of RNI’s shortwave frequencies, 6205 kHz. The report noted a SINPO code of 32332 and interference from Morse code on the frequency. A Tempest HF3 receiver was used, connected to a 20-foot longwave antenna. The weather was clear, with a temperature of 50°F. The listener also listed the music that had been played and mentioned that the programme was filled with requests. This report came from Witbank, in the Transvaal province of South Africa.

Former colleagues of the crew on board knew how to make quicker contact than using the well-known address, PO Box 117 in Hilversum. I found an envelope addressed to ‘Graham Gill, aboard the MEBO II, c/o Dick Roos, Treilerdwarsweg 8a, Scheveningen, the Netherlands.’ This was then the home address of the owner of the Triptender and the Eurotrip — the official supply vessels for RNI’s broadcasting ship. Inside the envelope was a postcard sent from Soest, in what was then West Germany. However, the sender was not on holiday in our neighbouring country:

“Dear Graham, as you’ve probably realised, I’m now in the army and the first month has passed. I still have 11 months to go, but life’s fairly manageable. I hope you’re enjoying your time aboard the MEBO II — give my best regards to all the other lads on Pierre’s ship.”

Regular listeners to the shortwave programme ‘RNI Goes DX’, broadcast on Sundays, will recognise this as a reference to Pierre Deseyn, who, along with Peter and Werner Hartwig, assisted A. J. Beirens with the programme.

Alongside the many postcards and letters, I found a variety of other memorabilia in the Amsterdam basement. One such item was a tiny photograph — stamp-sized — which I’ve greatly enlarged. It shows a DJ in the old Swinging Radio England studio: a photo of Radio Dolfijn DJ Jos van Vliet, taken by Look Boden at the end of 1966.

Another card sent from Germany was a kind of welcome note for Graham. It was written by Karl Heinz Pflundke, who wrote:

“Dear Graham, it was great to finally hear you on the radio again on 27 March (1973). You and Don Allen are the only offshore DJs from the 1960s still on the air. It’s an incredible feeling to hear you again. So many great DJs like Tony Allan, Andy Archer, Roger Day and Robbie Dale are no longer heard. RNI is the only station that still brings us memories of the sixties. I wish you lots of fun on RNI and don’t let the Dutch government drive you away.”

The card was written in March 1973 from Bochum. Not long after, he sent a second card and added:

“At last, RNI has the right people who can compete with DJs like Bob Stewart and Tony Prince on Radio Luxembourg. You just need a Top 40 instead of your current Top 30. Even without a longer chart, you’re a solid rival to Luxembourg. Could you ask the ship’s transmission engineer to note that RNI is easily the number two on medium wave, after ‘208’, and definitely number one when it comes to shortwave signal strength?”

Sometimes, people living within the broadcast range of a station still couldn’t receive it due to interference from another station on a nearby frequency. This happened in April 1974, according to a letter sent to RNI from Belgium:

“I was once a leading member of the Belgian Free Radio Campaign and I’m now an active member of the Free Radio Campaign Germany. Being a huge free radio enthusiast, I collect all kinds of promotional material from these stations — I’m particularly trying to collect every record related to the offshore stations. I’ve built a small collection so far. I’m still searching for a copy of ‘We Love the Pirate Stations’ by The Roaring Sixties. A friend recently gave me your address and said you might be able to help me find this record. Could you write back, Graham? I can’t receive RNI in my village due to interference from France Inter on 210 metres. I live just 15 miles from that transmitter. So I can’t call myself a regular listener to RNI, but I love the station because it’s an offshore broadcaster. I’ve signed up to take part in one of the upcoming offshore radio trips in June — perhaps I’ll see you aboard the MEBO II. I’m still fighting the good fight for free radio. Best of luck!”

I had a good laugh when I read this letter — it was signed by none other than Jean-Luc Bostyn, who, not long after, founded the magazine Baffle together with Frans Schuurbiers. The publication was later renamed RadioVisie, and today still exists as an online daily media news bulletin. When I recently asked Jean-Luc whether Graham had ever replied to his letter, he couldn’t even remember writing it — but then again, it had been nearly forty years. He once received a ‘Jacky Northsea card’ from Graham, which now made sense.

“Johnny Jason said on his show tonight that you’ll keep broadcasting on Radio Caroline from 1 September. I still don’t understand how that’s going to work, but I truly hope it does — otherwise, many listeners will feel terribly sad and lonely without their favourite stations. I just can’t imagine being without you on the radio. It’s comforting to know there are friends playing music for you and helping you through the night.”

She also mentioned Caroline’s LA Festival at Stonehenge in the same letter:

“There was a report on television last night about Stonehenge. They said all those camping there illegally would be taken to court if they stayed. So I suppose Caroline’s LA Festival might come to an end.”

I don’t go through the letters in strict chronological order, but simply pull another from one of the many suitcases. This time, I came across a letter from a woman named Chris. Her number was 2882548 and at the time of writing, she was held at H.M.P. Parkhurst in London — one of Her Majesty’s prisons. The letter was dated 8 August 1974:

“Dear Graham, as you can see from the address, I’m in prison — not mentally, just physically. I’m in the so-called drugs unit, and everyone here listens to Radio Caroline every evening. There are 14 of us girls, and in our single cells, we bang on the walls and doors whenever music by Pink Floyd or Hendrix comes on. When one of our radios runs out of batteries, the others turn theirs up even louder — at the risk of losing them for a week as punishment. I’m serving a two-year sentence and will be out next June. I’m trying to get back in touch with someone who I believe now lives in East Anglia. Could you read out my name, number and address? His name is Jacko, and I first met him in Portsmouth, where he was desperately trying to find a way to leave the Navy. My husband and I last saw him two years ago at the Lincoln Festival, where he was taken away by the anti-drugs squad. I’d really love to hear from him again.”

Chris’s letter also included the names of her 14 fellow inmates and more about their lives — much of which I won’t repeat here for privacy reasons.

As already mentioned, Graham had several female fans who wrote to him regularly — including someone named Olive. She often invited him to her home to enjoy her impressive strawberry beds. One day, she sent in a letter full of song requests, each beginning with a letter from “Graham Gill.”

When I began this series—by delving into the basement of Graham Gill and mining, among much other material, the specific radio-related items—I never imagined that so many episodes filled with memories could be published.

On 1 October, it was Jan Hage, then living on the Hongarenburg in The Hague, who wrote a long and interesting letter to Graham Gill, who at the time was aboard the broadcasting ship MEBO II.

“First of all, I’d like to thank you warmly for the tape you recorded for us, which included a few dedications for my wife and daughters, Karin and Diana, and certainly also for HaPro Services.” When I read that sentence, my mind drifted to the large production studio on board the RNI ship, and I pictured Graham, late at night, pulling a previously aired programme from the archive and placing it on one of the Revoxes to record the dedications and a commercial for the company. At the time, Jan Hage and his business partner were producing both corporate and family films.

But there was also a hint of regret in the letter: “Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to be at the harbour the last time you came off the ship. Later that Friday, I received the tape with the recordings from Dick Roos.” For those unfamiliar with the events surrounding RNI during the 1970s, Dick Roos was the owner of the supply company Trip, which operated the Trip tender and the Eurotrip for the provisioning of the MEBO II.

That same letter also mentioned a familiar name—Marian Pronk—who was often referred to in the programmes as a regular listener to the international service of RNI and who frequently wrote to various DJs. Jan wrote to Graham: “Perhaps you remember that Marian Pronk and I once gave you and Brian McKenzie a lift to Caroline House, and we dropped Brian off at the station in The Hague. Marian also took a photo of you and Brian in the Van Hoogendorpstraat. Later that day, we had a drink together at Marian’s place.”

It seemed certain promises hadn’t been fulfilled, as Jan continued: “At one point, you promised to record a special version of your theme tune, Way Back Home, complete with the sound of a kangaroo. Unfortunately, the track by Junior Walker and The All Stars is no longer available in the Netherlands. Our plan was to use it for a film we wanted to make about RNI.”

One wonders whether such a film ever came to be. Sadly, I’ve not been able to trace Jan Hage in any way. A bit of frustration followed in the letter: “As for Marian—you know her well by now—I can tell you she’s incredibly kind, honest, and a young woman of 24. When she listened to the tape, she was very disappointed that her name wasn’t mentioned. Marian is very sensitive and loves to hear her name on air. She’s also very shy. When Robb Eden last left Scheveningen for the ship, he promised Marian he would play a record for her that same evening on his RNI programme. She stayed up listening until three in the morning, but Robb didn’t keep his promise. Not a single record was played for her, let alone her name being mentioned. The next morning, she told me she’d been crying all night.”

One can’t help but wonder how deep the love for a radio station can run—or was this perhaps more about personal affection? The letter went on to mention that Marian had photographed various RNI personnel in the past and had shared those pictures freely with them and the station.

In Graham’s basement, I also found a notable promotional postcard from Radio Netherlands Worldwide, signed by F. Bruce Pearson, one of the station’s presenters. Dated 15 June 1973, it was addressed to RNI: “Dear Graham and all other DJs at sea. I’ve listened to your shows, both in English and Dutch, and I think you’re doing a marvellous job. If possible, please give David Ireland a good plug with his record Shoot the Family Man, backed with Coming Up Strong. It’s released on the Delta label, and David is available for an exclusive interview. Keep the sound swinging, and let Holland hear Ireland through David.”

Before joining Radio Netherlands, Bruce was well-known to listeners of the shortwave station WNYW from New York. That was a high-power station that could be received in many parts of the world. Incidentally, Graham would later become Bruce’s colleague when he too joined Radio Netherlands. They shared another curious connection: both appeared as newsreaders in songs released as singles. Graham featured as the newsreader in Melodrama by Bolland and Bolland, while the Canadian-born Bruce Pearson appeared as “Lovable Larry” in Late Night Show by Tiffany, released in 1979.

The next letter I uncovered had been sent from White Cottage, The Hill, Norwich, by someone I used to correspond with during the heyday of the offshore stations in the 1970s. It was written on 13 July 1973 by the late Anthony Platten: “Dear Graham, I hope you’re doing well. Last Tuesday I heard your programme and your mention of special photo stickers for listeners. I’d be grateful if you could send me one. I enclose two IRCs to cover postage. Did you receive the ‘Aftermath’ poster I sent a month ago? I hope you liked it. Thank you, Anthony R. Platten.”