It was in 1993 that I first reported on one Bob Peeters’ alleged plans to create an offshore radio station and more. In the book: ‘Historie van de zeezenders 1907-1973. About pioneers, thumb suckers and crooks’ highlighted a number of radio projects where the results were minimal when it came to the radio signals distributed.

Most of the projects described were never realised. So was the project in which one Bob Peeters turned out to be the foreman. More than 31 years after the first publication, partly because a number of people have started talking or rooting around in all the activities surrounding Bob Peeters and his delusion over the decades, I can come to a comprehensive but partly muddled reconstruction, partly because questions remain partly unanswered.

The story of Radio SOR, the Operation Radio Foundation, and the Hendrik-Jan. We spoke about this many years later, from our Media Communications Foundation, with Steph Willemsen and others. The then 36-year-old Bob Peeters, initiator behind the project, was able to report that 106 men were working diligently to complete the station. As many as 100 men were said to have been working behind the scenes in the administrative sector, in addition to a group of six young Portuguese, consisting of freedom fighters and deserters, led by Portuguese rebel Maria Sino Garcia.

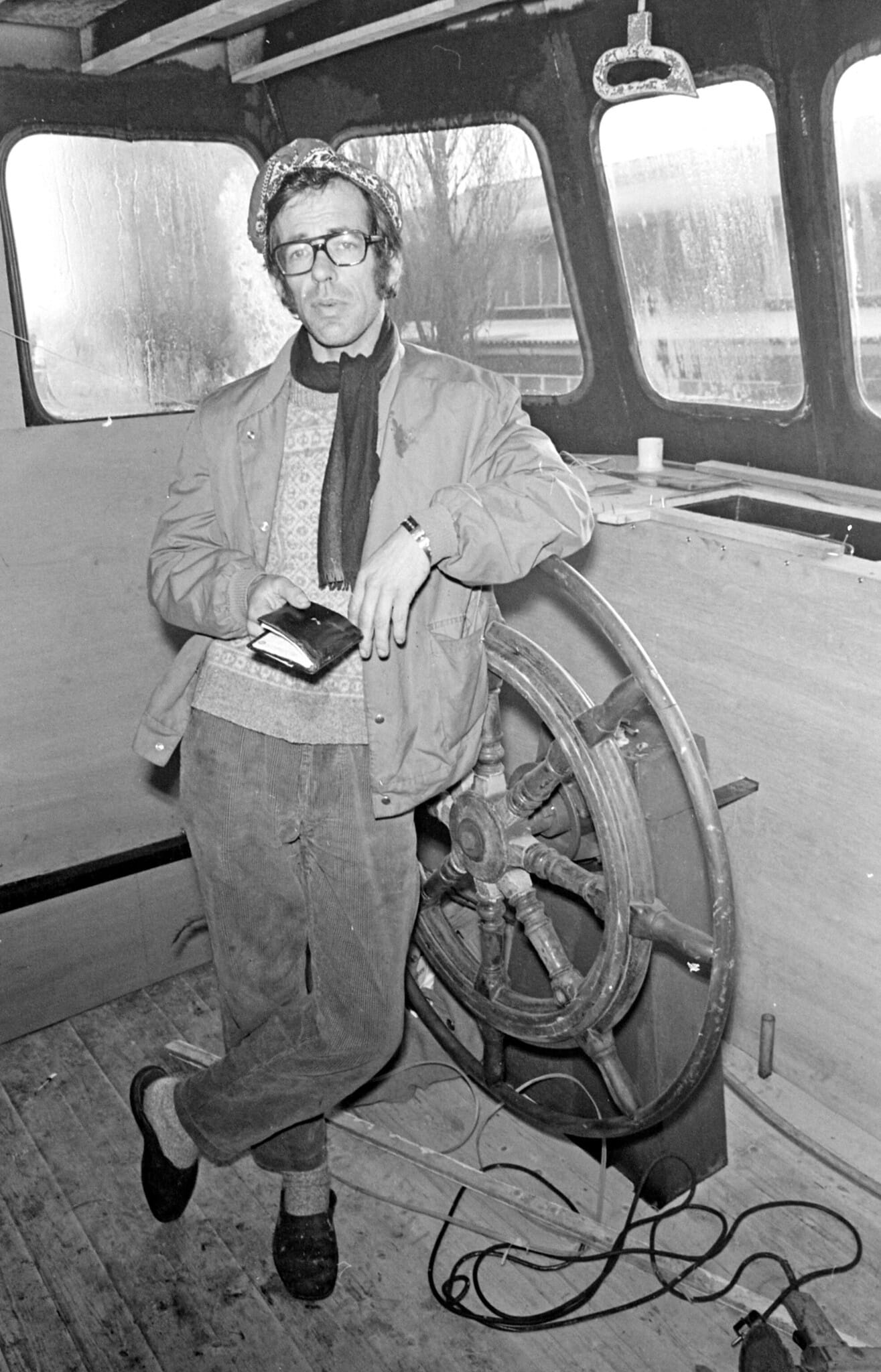

Peeters himself stated, ‘Radio SOR will be a freedom station with a Christian, humane, social and peaceful slant’. According to the planning at the time, it was planned that around March 1971 the 21-metre-long ship with a dozen-meters-high transmitter mast would leave Haarlem to storm the seven seas as a floating radio station. The North Sea was to serve as a test base. After that, the team would be deployed anywhere in the world, wherever needed in charitable areas.

According to Peeters, the project had a budget of 180,000 guilders, of which a ton was to be paid to Ms. Oosterveld. According to Peeters, she had previously bought the ship from the previous owner. The foundation, which never passed a notary, would pay this amount to Ms. Oosterveld in weekly sums of fl. 500 if the ship was sent ready. A little calculator soon finds out that it would take at least seven years to pay off this debt, let alone whether the amount reported was correct.

According to the Telegraph in a January 1971 article, the Portuguese were hard at work: ‘The crew is already sleeping aboard the (still) draughty and chilly Hendrik-Jan, on which fierce tinkering is going on during the day. A brand new central ship heating system is ready on the quay. The wooden panelling is already in the ship. The crew also swapped 1970 on board the ship for 1971. Someone from the neighbourhood came to bring one chicken for the boys, along with 25 guilders. The seven of them quickly picked the chicken.’

Peeters: ‘From that 25 guilders, we then bought oil. The late Reverend Toornvliet saw salvation in it and instructed Ms. Oosterveld, who was his secretary, to buy the ship. He thought he could cut through the loopholes by bringing ‘The Good News’ from the North Sea. Later, for financial reasons, Toornvliet came into conflict with the SOR and seemed to thwart its charitable plans. Fortunately, Oosterveld had already ordered the transmitters and equipment and we could go ahead with the plans. Consequently, we made the buy-off procedure with her.’

Peeters thought to put Toornvliet in a bad light while he himself dwelled in the category of ‘crooks’. ‘Toornvliet was a good pastor, but you couldn’t rely on him. Because he could preach so beautifully, we decided that we would broadcast his programmes but that he had to pay for them. And: ‘if we pray, the money will come,’ Toornvliet told us at the time.’ In reality, Toornvliet himself, or from his organisation, did not pay a single penny.

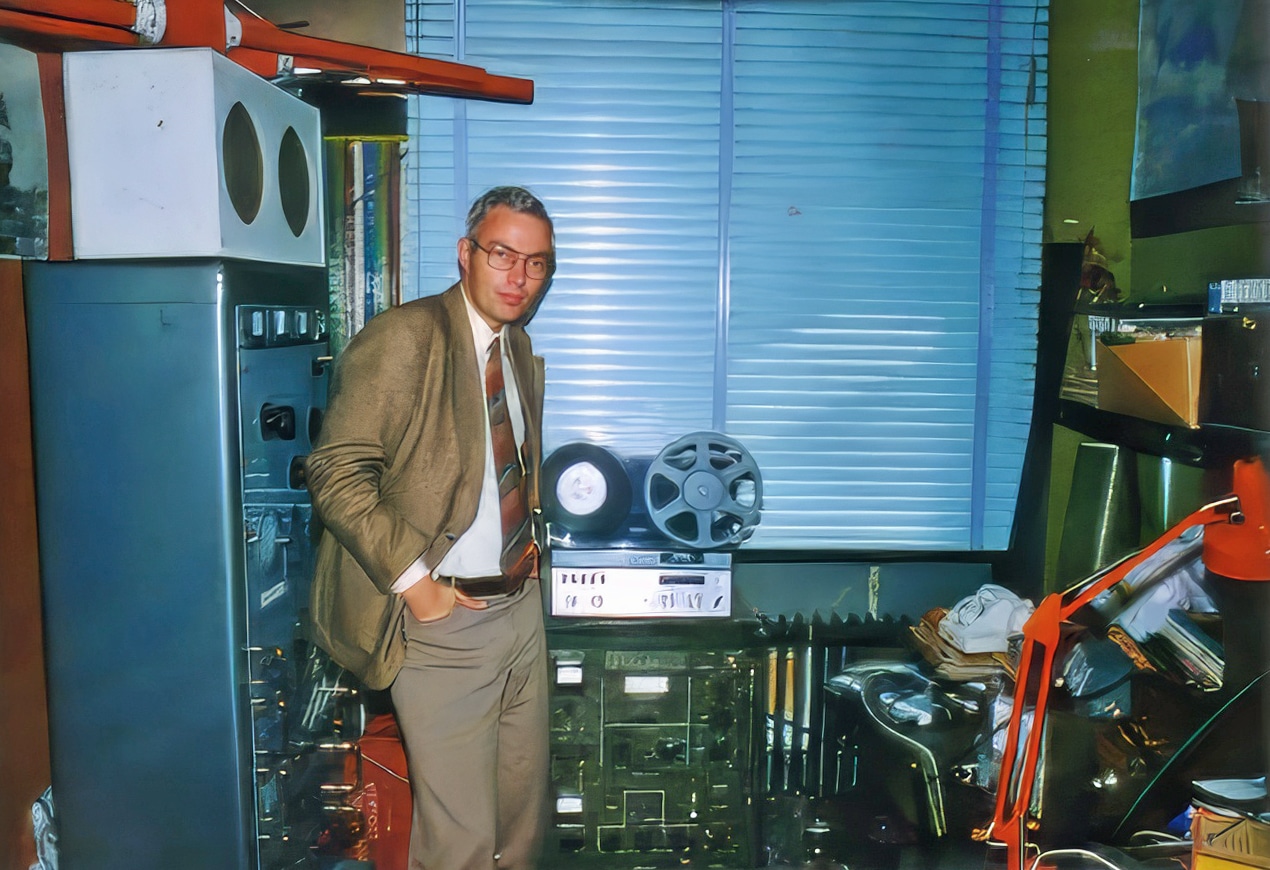

A number of newspapers managed to report in January 1971 that Bob Peeters had ordered a transmitter in England for a sum of fl. 20,000, which was actually supposed to fetch fl. 180,000. The transmitter built for India would have a power of 3.5 kW which would give a radius range of 360 km. Peeters had other plans. One was to install a special hydraulic mast so that during violent storms the mast could be lowered to prevent breaking off.

In early January 1970, the engine was offered to a machine shop for overhaul and Peeters reported that one would sail to underdeveloped countries to convert people. Through American example, jingle, play a record and short talk, people would be brought the message of the SOR. The Portuguese cause – at the time there was a fierce crisis in the country – would also be extensively exposed off the Portuguese coast.

Of course, Peeters’ ideas seemed nice but the first message immediately raised eyebrows among true offshore radio fans. Indeed, at the end of the article it was stated that they were not even able to pay the 150 guilders of weekly demurrage. So how was the ship ever supposed to function as a full-fledged radio station in the North Sea and elsewhere? The Portuguese, according to rumours, were staying illegally in the Netherlands. As previously reported, they were deserters from the Angolan army and members of the pacifist resistance who had fled Portugal.

However, one had reported them to the police and soon they were staying in our country on a temporary residence permit. They had struggled to get a job, but when they heard of Peeters’ plans, they were quickly persuaded to join the project given that the Portuguese cause would also possibly be fought for. Just days after the first reports about the Hendrik-Jan appeared in the national press, ‘the owner of the ship’ had the engine and other parts safely stowed away to prevent Peeters and his Portuguese counterparts from setting sail to start programmes as yet. It had long been realised that they would not be able to pay the promised weekly 500 guilders.

Besides, the ship was not seaworthy at all and was in danger of sinking immediately in the first storm, even a few hundred metres off the coast. The Portuguese also realised that their Messiah, ‘Capitano Peeters’, was not the great saviour after all, and decided to go into labour in Velsen. Peeters did not leave it at that and immediately went looking for another boat, which did have an engine. He found it in IJmuiden with Mr. H. de Boer.

Peeters himself stated that he could buy the boat for fl. 25,000, but de Boer reported that the ship would cost at least fl. 40,000. And so this plan fell through. Eventually, the Hendrik-Jan was towed away and scrapped by the yard’s owner. Peeters was left with a hangover, although he did manage to fool someone within Reverend Toornvliet’s organisation and get some publicity with his ‘fake’ offshore radio project.

But after the first two publications I wrote about the SOR, a lot more came to light. Partly because SMC got hold of Max Lewin’s clippings archive around 2008, which included many radio-related topics. But also because of conversations SMC (Stichting Media Communicatie) foreman Rob Olthof had with Steph Willemse and recorded them on paper in telegram style. And certainly the name of Ary Jassies should also be mentioned here, who was an excellent research journalist at the time and also dived into the SOR project in early 1971.

Among other things, Rob asked Steph Willemse why nothing had come of the SOR and in response he stated: ‘’Bob Peeters’ engineer figured out that he could put a mast in the middle of the boat. The boat was definitely not 350 tonnes, as people claimed, and so would rock like a match in the churning water on the North Sea. It was more like a depreciated luxury inland waterway vessel and so of course this mad plan to take the ship into the North Sea was abandoned.’

Rob was also interested what eventually happened to the Portuguese. Steph: ‘They were no longer looked after, not even by Geert Toornvliet. Humanitarian was only the immediate surroundings, because at Christmas in 1970 the Portuguese were provided with wine and chicken with bread by residents on the Spaarne in Haarlem. Nothing was ever heard of Bob Peeters again.

In the 1970s and 1980s, I received dozens of phone calls from people who wanted a boat at sea. For instance, one Belgian called me who had a barge full of gravel and wanted to start an offshore radio station with it. His question was if I could just provide the necessary financiers and auxiliaries. He also had extra generators on the quay and wondered where he could buy transmitters. At Vroom and Dreesmann in the Netherlands, I replied. Never heard from the man again.’

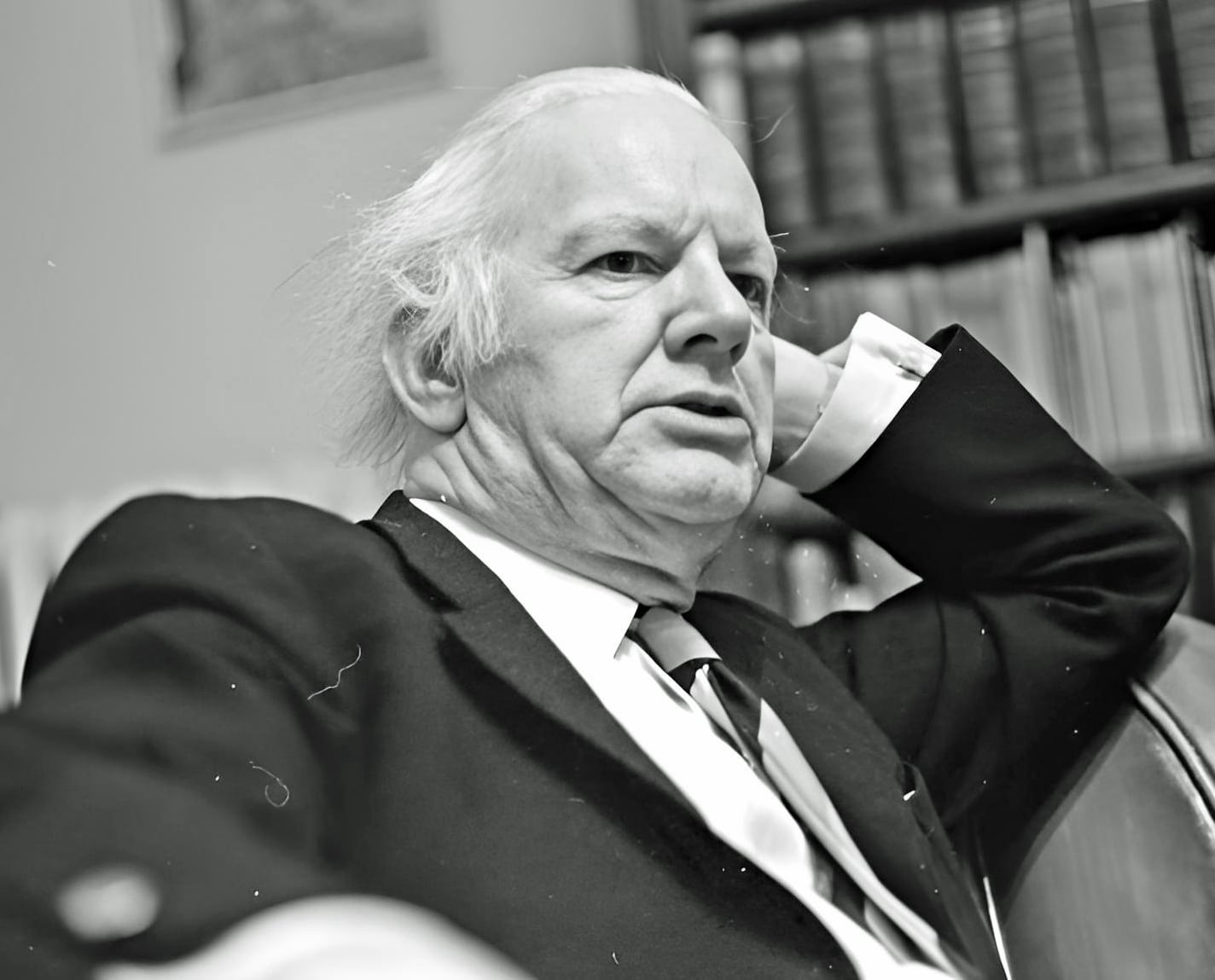

The next question Steph was allowed to answer was: But hadn’t Toornvliet, through his assistant, made a considerable sum of money available to Peeters for that time? Steph: ‘Not true, but his adviser did donate the necessary money from her own budget. As early as May 1970, Rev. Toornvliet, who at the time was also active for Capital Radio and a station in Paramaribo and in later years could also be heard on Radio Mi Amigo and Radio Caroline, had been approached by Peeters. In a conversation, Toornvliet soon realised it was not a good plan to invest a hefty sum as he did not trust Peeters.’

The former investigative journalist Jassies published his article on Peeters on 16 January 1971, stating that Toornvliet had reported to him: ‘The plan was nice but the figure too dubious which he also let his assistant know.’ So in retrospect, it was not Toornvliet who invested but his assistant who appealed to her savings and suggested to Peeters to buy the boat, partly from her money.

Jassies managed to report that Ms. Oosterveld was certainly not the only person who had been swindled by Peeters: ‘It was Mr Weiler, staff officer at the Red Cross in Amsterdam who listened eagerly to Peeters’ stories.’ Weiler turned out to be so enthusiastic that he made as much as 85,000 guilders available, this partly Peeters’ plans to also organise sailing trips with the ship, each time allowing disabled children to come along. A day out, as it were. But Weiler later stated that he had fallen for Peeters’ plans with open eyes and could therefore whistle for his money, which also meant for Ms. Oosterveld that the investment she made in the Hendrik-Jan would never be recouped.

And Peeters had his fantasies because he assumed he could certainly take this pleasure yacht out to sea. In interviews, he went wild by claiming he could even sail to the African interior to provide books and medical assistance and certainly take a minister on board for religious and anointing messages.

At the time, Jassies also delved into the past of the Zaandam-born Peeters, who had worked as a street photographer, among other things, and concluded, ‘Suspected of several offences against law and authority, he disappeared to Spain in 1963 but also got into trouble there for not returning a rented car.’ Further investigation revealed his alleged involvement with the Belgian Foreign Legion.

Peeters himself stated in 1970 that he had done everything forbidden by God in his life. ‘I have really been a bad dog who has been in touch with justice everywhere’. Mysteriously, the question remains whether some of Weiler and Oosterveld’s savings have resurfaced. What is very clear, however, is that the Hendrik-Jan was never used as a broadcasting ship for a charitable purpose and that Peeters disappeared from the horizon.

Hans Knot 2025

P.S. Toornvliet did so through Radio Luxembourg, Capital Radio, Radio Paramaribo and Radio Mi Amigo and Radio Caroline: