The Radio Station of the German Freedom Party

A historical reportage by Martin van der Ven

The “Radio Station of the German Freedom Party” was the first European and only German offshore radio station. Remarkably, it served a political purpose – resistance against the Nazi regime. The radio creators were German journalists living in exile, supported by Dutch, British, and French collaborators in their courageous but unfortunately short-lived project.

Lesen Sie hier den deutschsprachigen Text.

The only German offshore radio station. It’s well known that in the latter half of the last century, numerous radio ships appeared off Europe’s coasts to broadcast pop and rock music. The investors and staff usually came from Britain, the Netherlands, Belgium, or Scandinavia. When asking offshore radio experts about German-speaking staff on these international waters’ radio stations, names like Rudi Kagon (machinist on the Mebo II at Radio North Sea International), the two RNI DJs Axel and Hannibal (later known as Ulf Posé), Dennis King (manager and DJ at Radio Caroline), Johnny Jason (DJ at Radio Caroline, real name Rüdiger von Etzdorf), and Jürgen Wellmann (mechanic at the Voice of Peace) are often mentioned. Swiss staff such as Elke, Edwin Bollier, Erwin Meister, Urs Emmenegger, Bruno Brandenberger, Kurt Baer, Victor Pelli, and Eva Pfister (all also at RNI) are also relatively well-known, as are Austrians Horst Reiner (RNI) and Manfred Sommer (technician on the MV Fredericia at Radio Caroline North from 1965 to 1968). On the MV Bon Jour (Radio Nord), Hamburg sailors Reinhold Knies and Horst Helmsieck, along with kitchen helper Karin (Knies’ fiancée), worked. In addition, the “Offshore ’98” experiment by several German radio enthusiasts over the Easter weekend in 1999 garnered some attention.

But who knows about Jakob Altmaier, Ernst Langendorf, or Carl Spiecker? To understand their story, we must go back to 1938. Back then, the “Station of the German Freedom Party” operated from the radio ship “Faithful Friend” on shortwave. This first European and only German offshore radio station served a political purpose – resistance against the Nazi regime. German journalists in exile ran the station, supported by Dutch, British, and French collaborators in their bold but unfortunately short-lived project. Let’s turn back the wheel of history…

Carl Spiecker and the German Freedom Party. It’s January 1938. Hitler has been in power in Germany for five years, and World War II is looming. At this point, 50-year-old journalist

Dr. Carl Spiecker (born January 7, 1888, died November 16, 1953) was Ministerial Director and Press Chief of the Reich Government from 1922 to 1925 and had led a special department to combat National Socialism under Heinrich Brüning’s government in 1930/31. In the conservative Center Party, Spiecker was part of the more left-oriented group of loyal republicans around former Chancellor Heinrich Wirth, who was Interior Minister under Brüning in the early 1930s. After the Nazis took power in January 1933, Spiecker was dismissed from his state position for “political unreliability.” He fled abroad, spending the time until 1945 in France and England, later in the USA and Canada. Under the pseudonym Miles Ecclesiae, he published the pamphlet “Hitler against Christ” in 1936.

Presumably around the turn of 1936/37, Otto Klepper (born August 17, 1888, died May 11, 1957) and Carl Spiecker founded the “German Freedom Party” (DFP) in French exile together with other liberal-conservative politicians. Willi Münzenberg (born August 14, 1889, died June 1940), who had increasingly fallen out of favor with the KPD, also acted in the background. This conspiratorially operating group aimed to unite various political and religious directions into a “people’s front without communists.” From 1938 onwards, Carl Spiecker, Hans Albert Kluthe (born July 15, 1904, died December 13, 1970), and Dr. August Weber (born February 4, 1871, died November 17, 1957) gained influence. The party saw itself as a national freedom movement that wanted to end the reign of terror for human, Christian, and national reasons. They opposed the Hitler dictatorship from abroad in as much anonymity as possible, with a national program and contacts with the Wehrmacht, churches, the economy, and student groups in Germany. Although the DFP claimed to be a resistance movement within the German Reich, it must be considered an emigrant group.

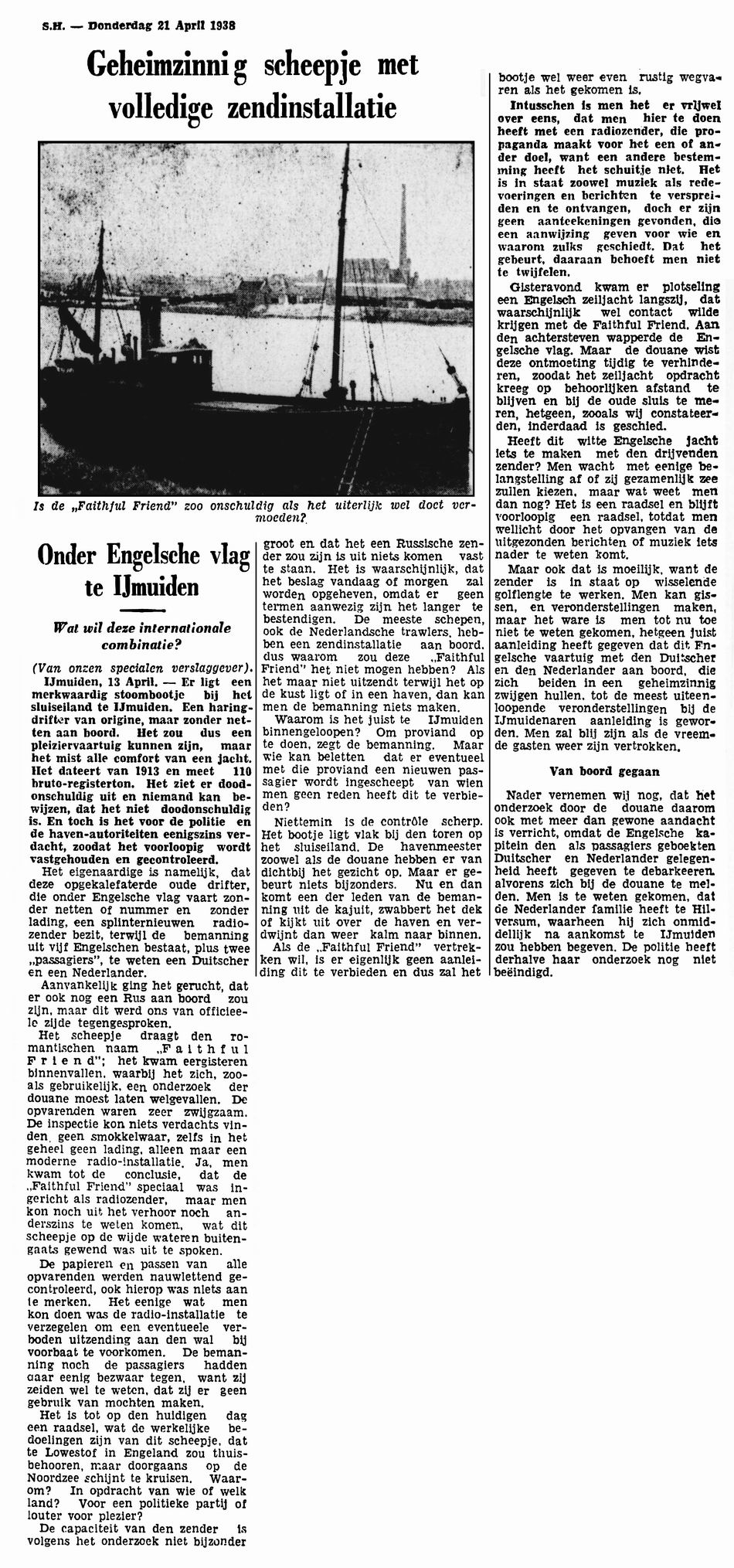

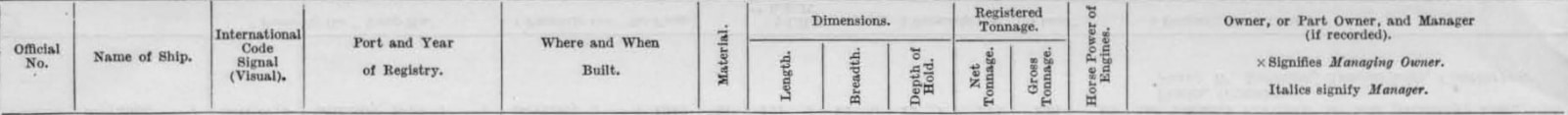

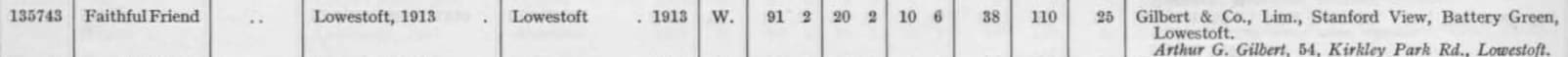

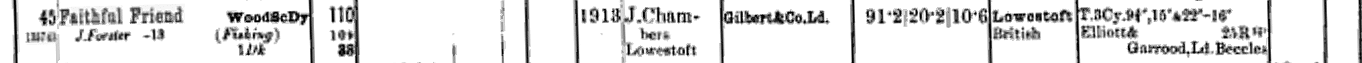

The Station of the German Freedom Party and the Faithful Friend. Besides his publishing activities, Carl Spiecker discovered radio as a medium for his political activities and resistance against the Nazi regime. Presumably from the second half of February 1938, he used the ship “Faithful Friend,” registered in the English port city of Lowestoft (county of Suffolk), to broadcast radio programs against the Nazi regime. The ship, built in 1913 by the shipping company John Chambers Limited & Co. in Lowestoft, was a steam-powered fishing trawler with 110 gross and 38 net registered tons. The ship’s dimensions were 27.8 m in length, 6.2 m in width, and 3.2 m in draught. The trawler belonged to Gilbert & Co. Ltd in Lowestoft, had the registration number 135743, and sailed under the call sign LT33. The steam trawler had a propulsion of 18.64 kW, generated by a triple-expansion steam engine. The ship had served the British Navy from 1915 to 1919 for laying defense nets. On February 18, 1938, the ship was sold to Wessex Drifters Ltd (manager Simon Munday, 77 Victoria Park Road, London). It is presumed that Wessex Drifters Ltd was a cover company founded by the SIS. The final owner was the salvage company Risdon Beazley Ltd in Southampton from March 23, 1939. The Faithful Friend was likely scrapped at the end of 1939.

The fishing trawler “Faithful Friend”

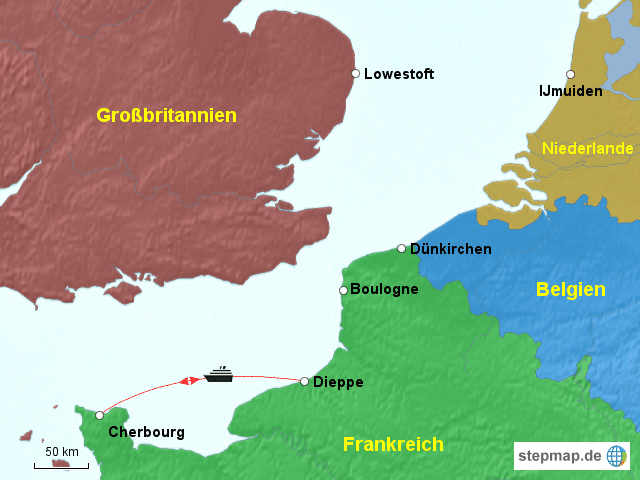

The trawler cruised under the British flag in international waters of the English Channel off the Dutch and especially the northwest French coast between Dieppe and Cherbourg. While serving as a radio station, eight men were on board: the captain, a cook, four sailors and stokers (all English fishermen), a German journalist who also acted as the “radioman,” and a Dutch radio technician. Spiecker’s radio station “Station of the German Freedom Party” was supported by two experts from VARA in Hilversum, who alternated on board. One of them was D. J. Fruin, the chief technician of VARA. They used a shortwave transmitter with an output of less than 5 kW. The transmitting equipment was reportedly prepared by British technicians. The project’s preparation was carried out under utmost secrecy, with the British government officially not informed. The frequency was 7842 kHz with a wavelength of 38.26 m (one report also mentions 10070 kHz). A “situation report” by the Gestapo in Karlsruhe noted at the end of April 1938 that “the ‘Freedom Station’ was heard several times in the reporting month on wave 29.8 and 38.25.” This is presumably a mistaken identification with the KPD’s “German Freedom Station 29.8,” which also broadcasted its programs on shortwave from Spain at that time.

Available sources suggest that Carl Spiecker, as the initiator and organizational and editorial head of the radio station, was not himself on board the broadcasting ship. He evidently wrote his texts in Paris, from where they were sent to a cover address in the port where the Faithful Friend docked. Spiecker also frequently contacted his collaborators by phone when they were on land.

British authors speculate about the financial and intelligence backgrounds of the project. Exact evidence is hardly to be found. Carl Spiecker was known to be particularly secretive, even towards his employees. Even his family seemed to be only partially informed about his activities during exile. Spiecker had to cover the costs for food and wages for the ship’s crew, finance the fuel (coal for the ship’s engine and gasoline for the generator motor), and procure the broadcasting equipment. However, he had numerous contacts with British underground organizations. Jakob Altmaier and Carl Spiecker are listed in the directory of “Officers, Agents, and Main Contacts of Section D of the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS, alias MI6).” Founded in April 1938 (thus only at the end of the broadcasts from the Faithful Friend), it received permission to commence activities in March 1939 and eventually formed the core of the Special Operations Executive (SOE).

The Social Democrat Fritz Heine, also living in exile (December 6, 1904, † May 5, 2002), presumably served Spiecker as an advisor and intermediary to the British. Sir Campbell Stuart, who had his office in the Department Electra House and simultaneously chaired the Cable and Wireless Company, may have helped finance the offshore radio project. Commander Kenneth Cohen from Colonel Claude Dansey’s secret “Z” Organization of the British Intelligence Service SIS likely assisted Spiecker as well. An English source even suggests that the influential and wealthy Hungarian-British film producer and director Alexander Korda might have financially supported Spiecker on behalf of the SIS.*

However, the reality on board the small and uncomfortable broadcast ship involved significant deprivations and extremely harsh living conditions for the staff, who undertook the mission with immense courage, idealism, and civil bravery. The constant smell of fish on the uncomfortable trawler and the high seas at the end of winter led to nausea and seasickness.

The European idea, so often evoked in the post-war period, was already vividly realized in this small space: German journalists, Dutch technicians, English sailors, and French authorities cooperated in remarkable political harmony, an example only comparable in radio history to the offshore station Radio Brod operating off the Adriatic coast during the Yugoslav wars in 1993/94.

On board: Jakob Altmaier and Ernst Langendorf. The editors and moderators on board the broadcast ship Faithful Friend were two Social Democrats, initially Jakob Altmaier (November 23, 1889, † February 8, 1963) and shortly thereafter Ernst Langendorf (December 15, 1907, † December 7, 1989).**

The “Sender der Deutschen Freiheitspartei” (Radio Station of the German Freedom Party) was probably first heard in February 1938 (an exact start date is not known; at least the sale of the ship to Wessex Drifters Ltd did not occur until February 18). The station announcement was: “This is the radio station of the German Freedom Party!” The broadcasts were intended to be heard daily, normally from 7:30 PM to 8:00 PM and from 10:00 PM to 10:30 PM. If weather conditions permitted, the programs were repeated several times per night. In case of a storm, the ship could occasionally not leave the harbor, so broadcasts had to be canceled. They read news from around the world, but mainly from Germany. This was followed by political commentary and an international press review, as well as calls to resist the Hitler regime. The aim was to inform the German population about the “true nature of the Nazis” and its war intentions. Altmaier and Langendorf provided detailed reports in their broadcasts about the Condor Legion, through which the German Reich government was involved in the Spanish Civil War. Regarding January 13, the anniversary of the 1935 Saar referendum, they spoke of a “rigged referendum.” According to a Gestapo situation report in Karlsruhe, the radio station called for a “No” vote in the April 10, 1938 referendum on the “Anschluss” of Austria to the German Reich. Moreover, they explicitly declared themselves to be the mouthpiece of the German Freedom Party and solicited membership in this party.

A look back. Decades later, in April 1976, Langendorf gave the following recollections of the radio station of the German Freedom Party, translated back from English, to the German Radio Archive:

“The first editor and radio speaker on board was Jakob Altmaier… But after just a few days he quit, as the working and living conditions on this dirty and primitive, coal-powered ship were simply too much for him during the January storms… I reached Dieppe in mid-January. The stormy sea in January had forced the entire fishing fleet into the harbor. Nevertheless, we set out to sea the next afternoon. After just a few hours, I was drenched to the skin due to the high waves and so seasick that I was quite incapacitated. Ready to die, I sought out my small cabin. The captain eventually returned to the harbor. During the night, the storm subsided, and the next afternoon the sea was fairly calm, so we made a new attempt. This time everything worked. The Dutch technician from Radio Hilversum got the broadcasting equipment ready (the electricity came from a gasoline-powered engine). We broadcasted on 38.25m in the shortwave range. At 7:30 PM, I sat in front of the microphone and read the station announcement: ‘This is the radio station of the German Freedom Party.’ Then followed news, an international press review, a commentary, and various informative program segments. The broadcasts lasted 30 minutes each and were regularly interrupted by the station announcement. This included mentioning the wavelength and the broadcasting times (daily from 7:30 PM to 8:00 PM and from 10:00 PM to 10:30 PM).

This continued for a few weeks, in total about 3 months (I can’t remember the exact times anymore). Due to my seasickness, the broadcasts had to be shortened or even canceled several times. We only went ashore when we needed food or new newspapers. I got the news from German, English, French, and Swiss radio stations. I wrote the commentaries using the literature I had brought on board. Whenever we were in the harbor, I would call Dr. Spiecker in Paris, who provided me with information, advice, and instructions. I also stocked up on newspapers and magazines then.”

At times, the broadcast ship Faithful Friend was reportedly shadowed multiple times by a French warship to prevent it from entering national French waters during broadcasts. The French government also reportedly ordered direction finding to precisely locate the transmitter. The French authorities, who were apparently well-informed about the true mission of the ship, left the Faithful Friend undisturbed during its stays in the harbor.

In various radio interviews, Ernst Langendorf additionally reported:

“(Dr. Spiecker) had set up a small organization in exile. It was called

Dr. Spiecker asked me if I would be willing to go on this ship and broadcast news and commentary in German for the population in Germany. I thought it was a great idea: to do something meaningful and finally tell the Germans what they had done to themselves with Hitler and that this Hitler would surely start a war sooner or later that he would have to lose. That was my motivation: to do something against this regime.

In March 1938, the Germans invaded Austria. Hitler occupied Austria, and you can imagine how busy I was in my radio broadcasts, passing on the international reaction to Germany from the international press – as far as I could get hold of it.

We naturally had no news editorial staff. I was the only (editor) on this ship.

During the day, I always sat at the radio, at a receiver, and took notes on reports from the English, French, Swiss, and German broadcasts. I then made my news broadcast from these notes and was on the microphone twice every evening for half an hour each – first a longer news broadcast. Then I always had newspapers and magazines, also books with me, so I wrote commentaries, which I also read out myself.

Whether (the German Freedom Party transmitter) was received in Germany is very hard to determine. I only know for sure that it was monitored by the Gestapo, because in a military history archive in Freiburg there are reports of an intercepted broadcast from this transmitter, which is named in full in those reports. Dr. Spiecker (…) had connections in the Scandinavian countries and had asked his friends there to always tune in when this station was broadcasting. He had them report on the reception quality, etc. But of course, that says nothing about the listenership in Germany, which was certainly small.”

A fortunate ending. At the end of 1937, Germany had

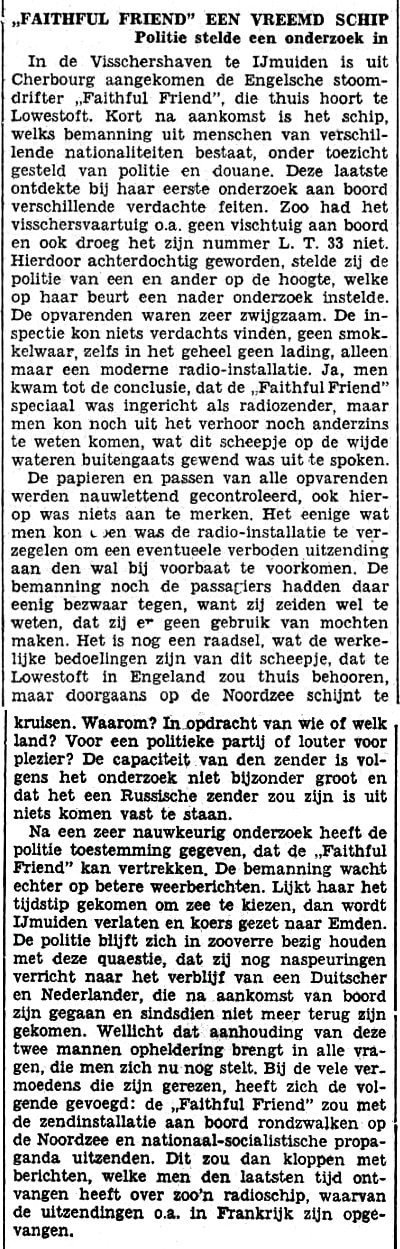

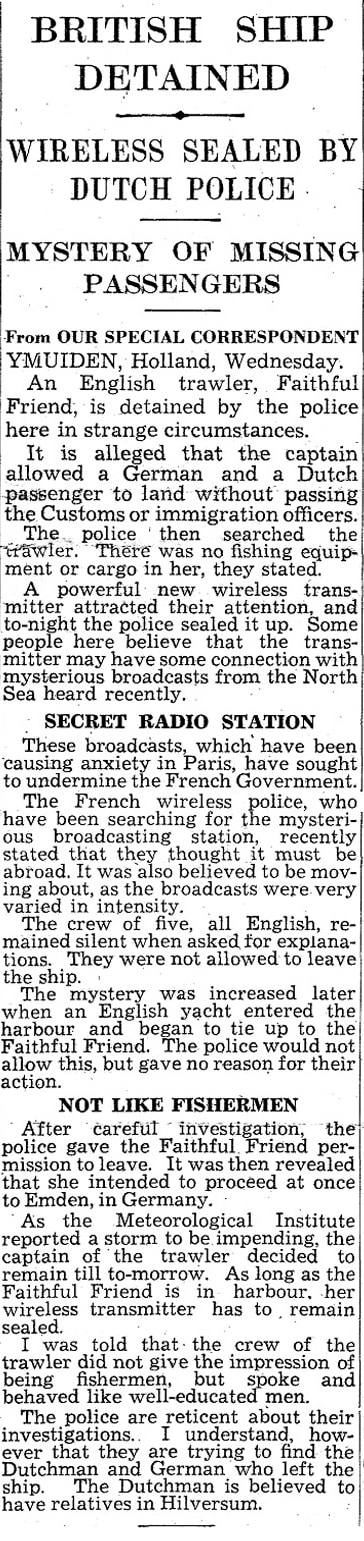

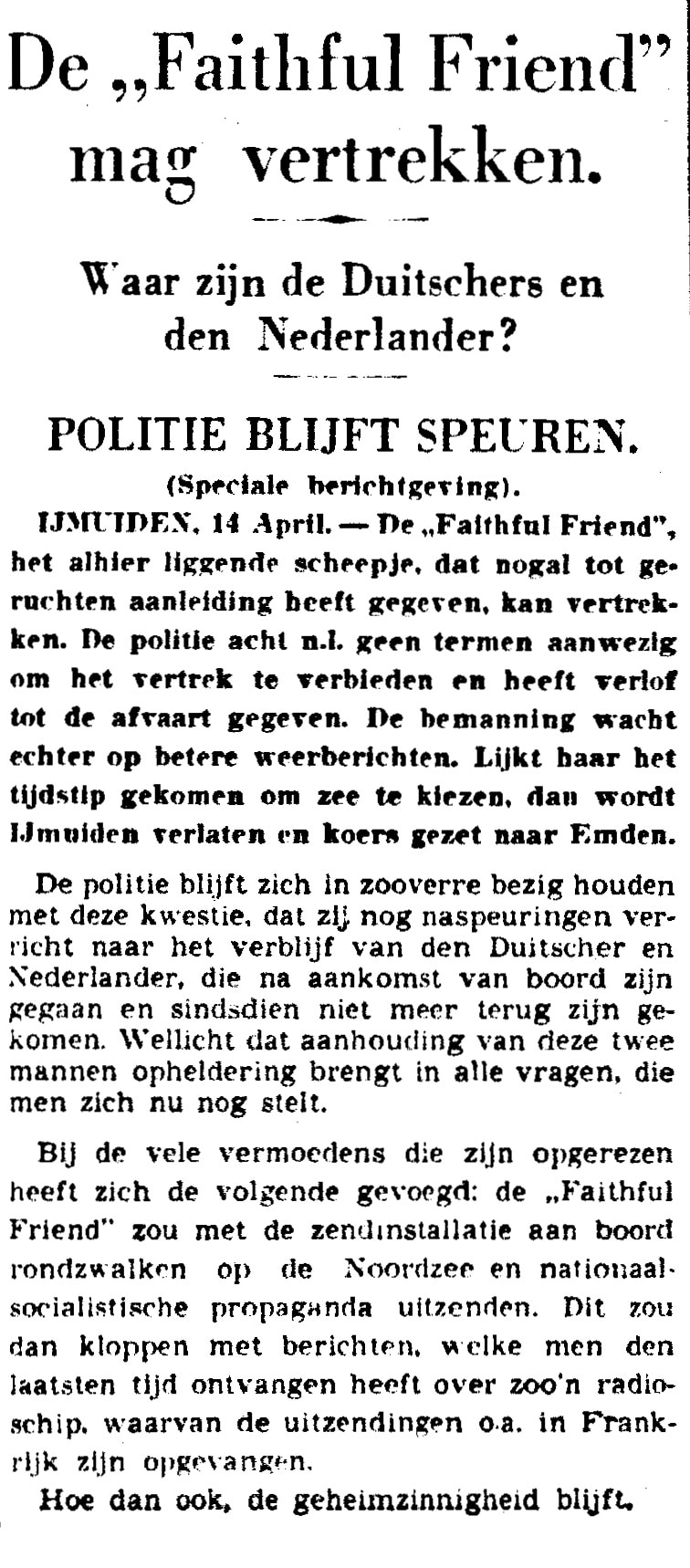

The crew in the harbor of Cherbourg followed Carl Spiecker’s recommendation and sailed to IJmuiden in the Netherlands on April 12. Langendorf: “When we docked early in the morning, the boat was thoroughly inspected and controlled by customs officers and then by a group of harbor police officers.” The authorities sealed the transmitter and checked the crew members’ papers and passports. Langendorf had to accompany them to the station, where there was a silent confrontation with a German officer wearing a Nazi badge on his lapel. Langendorf: “He was allowed to observe me, but he did not ask me any questions and soon disappeared again.” Apparently, the German embassy had been informed and involved beforehand.

The broadcast ship immediately sparked speculation in numerous Dutch newspapers. Not only did the “Telegraaf” report on the conspicuous old fishing boat. Stefan Appelius quotes the newspaper in his insightful article “Pirate in Resistance”: “The strange thing about the whole matter is the fact that this old, patched-up fishing steamer has a brand-new radio transmitter… From time to time, a crew member comes out of the cabin, cleans the deck, or just looks over at the harbor. Then he silently disappears again.” Particularly peculiar about the mysterious “herring cutter without fishing gear” was that, in addition to five English crew members, there were a German and a Dutchman on board as “passengers” who could identify themselves but otherwise remained silent. The conspicuous modern radio transmitter (possibly from Russia) might be used for political propaganda broadcasts. On the other hand, almost every ship nowadays has a transmitter…

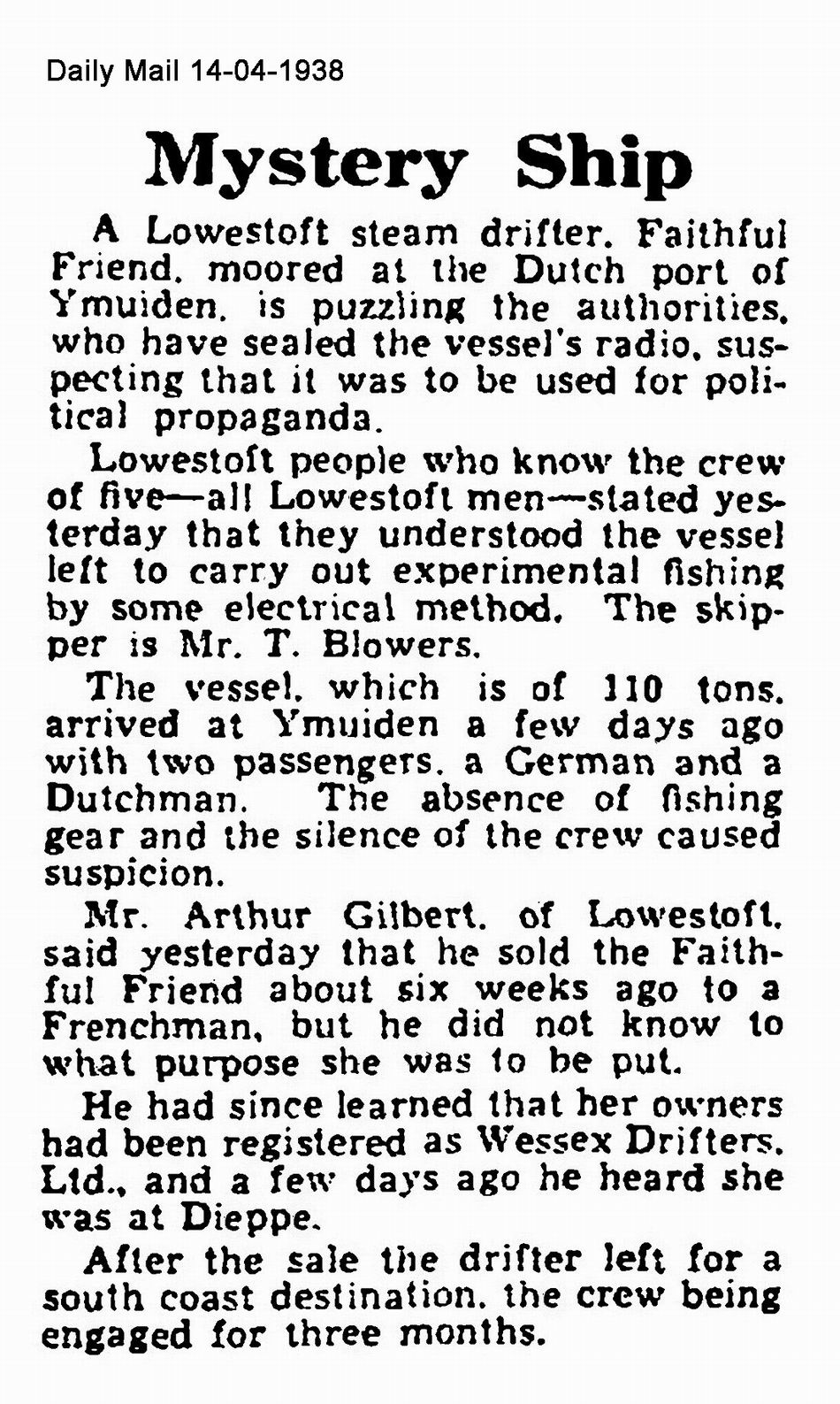

The English Daily Mail also pondered the situation. The captain of the Faithful Friend was named Tom Blowers, and in Lowestoft, it was said that the cutter was to conduct experiments with electric fishing methods. The former owner from Lowestoft, Arthur Gilbert, had sold the boat to a Frenchman about 6 weeks earlier. He later learned that the company Wessex Drifters Ltd was registered as the new owner. The crew on board had received a contract for 3 months.

The transmitter was eventually stored in a warehouse in Boulogne-sur-Mer, and the ship returned to England. Langendorf returned to Paris on April 16 (Holy Saturday) and learned that Carl Spiecker had meanwhile hired a comfortable motor yacht, which was also to be equipped in Boulogne-sur-Mer. However, during a test run, the yacht caught fire after gasoline was spilled in the galley. The boat was then a total wreck. Frustrated, Spiecker gave up his courageous radio ship project.

What happened next. One of the main objectives of the German Freedom Party from the beginning was to inform the German population about Hitler’s war intentions. After the outbreak of the war, all predictions and fears came true. However, Spiecker did not want to give up the fight. The German Freedom Party existed until early 1941, but it was never officially dissolved. Between May 16, 1940, and March 15, 1941, Spiecker and his comrade Hans Albert Kluthe broadcast once again from a radio station, now located on British soil – in Woburn near Bletchley, northwest of London. Due to the poor organizational structure of British propaganda at that time, the two-man editorial team had remarkable journalistic independence. The radio station, often referred to in literature as the “Freedom Station,” broadcast with the announcement “This is Germany on the 30.2 wave…” and transmitted on shortwave between 30.2 and 30.6 meters. Spiecker and Kluthe aimed to address a national-conservative audience, arguing that a “true German could not possibly be a Nazi.” This station was the first of many British covert stations, also known as “gray” stations. It did not operate as an officially British station nor did it identify as an illegal German station.

In June 1941, Carl Spiecker traveled to Canada for unclear reasons. He returned to Germany after the war ended in 1945 and played a significant role in the reestablishment of the Centre Party. In December 1948, Spiecker was elected federal chairman of the Centre Party. However, as he pursued a merger between the Centre Party and the CDU, he had to resign two months later and was expelled from the party. Spiecker then joined the CDU. From September 1949 until his death in November 1953, Carl Spiecker served as the plenipotentiary of North Rhine-Westphalia to the federal government.

Jakob Altmaier lost 30 of his relatives in the Nazi concentration camps. He was one of the few Jewish emigrants who returned to Germany after the end of the terror. From 1949 until his death in 1963, he was a member of the German Bundestag for almost 14 years as an SPD representative. He is considered a pioneer of the Luxembourg Agreement on reparations between Israel and the Federal Republic of Germany in 1952.

Ernest Langendorf lived in the USA from 1941. In 1942, he joined the US Army and thus obtained American citizenship. With the advance of American troops, Ernst Langendorf came to Munich in the spring of 1945 as an American soldier. He primarily served as an interpreter and specialist in psychological warfare. On April 30, 1945, he drove his Jeep to Munich’s Marienplatz, even before the 42nd Infantry Division “Rainbow” occupied the city. In June 1946, Langendorf was tasked as the press officer of the Office of Military Government US for Bavaria with licensing newspapers. He subsequently founded 25 press outlets, including the Süddeutsche Zeitung. From 1953, Langendorf worked as the press chief of Radio Free Europe in Munich and for 20 years as the head of the “German Affairs” department of this US radio station. Until his death in 1989, Langendorf was one of the two deputy chairmen of the International Press Club Munich.

Ray Robinson produced the following feature about The Radio Station of the German Freedom Party for the DX programme Wavescan (20 October 2024):

Sources Used:

Appelius, Stefan: Pirat im Widerstand. Anti-Nazi-Sender auf hoher See. Tagesspiegel, September 19, 1993.

Atkin, Malcolm: Section D for Destruction. Forerunner of SOE. Pen & Sword Books Ltd, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, 2017.

Berg, Jerome S.: The Early Shortwave Stations. A Broadcasting History Through 1945. McFarland & Company, Jefferson, North Carolina, 2013.

Bouvier, Beatrix: Die Deutsche Freiheitspartei (DFP): Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der Opposition gegen den Nationalsozialismus. Frankfurt, Dissertation, 1972.

Butcher, David: The Last Haul. Recollections of the Days before English Fishing Died. Poppyland Publishing, Lowestoft, 2020.

Düwell, Kurt: “Hier spricht Deutschland auf Welle 30,2 Meter”. Carl Spiecker als Stimme des deutschen Widerstands in den britischen Geheimsendern 1940/41. In: Jörg Hentzschel-Fröhlings, Guido Hitze, and Florian Speer (eds.): Gesellschaft, Religion, Politik. Festschrift für Hermann de Buhr, Heinrich Küppers und Volkmar Wittmütz. Books on Demand, Norderstedt, 2006.

Garnett, David: The Secret History of the PWE. The Political Warfare Executive 1939-1945. St Ermin’s, 2002.

Hensle, Michael P.: Rundfunkverbrechen. Das Hören von “Feindsendern” im Nationalsozialismus. Metropol-Verlag, Berlin, 2002.

Howe, Ellic: The Black Game. British Subversive Operations Against The Germans During The Second World War. Queen Anne Press, 1988.

Institut für Zeitgeschichte, Munich, and Research Foundation for Jewish Immigration, Inc., New York. General Editors: Werner Röder and Herbert A. Strauss: Biographisches Handbuch der deutschsprachigen Emigration nach 1933. K. G. Saur, Munich, 1999.

Jolly, Stephen: Ungentlemanly Warfare: A Reassessment of British Black Propaganda Operations 1941-1945. Falling Leaf: The Journal of the Psywar Society, 171, 148-156; 172, 23-37 (2001).

Kiene, Claudius: Karl Spiecker, die Weimarer Rechte und der Nationalsozialismus. Eine andere Geschichte der christlichen Demokratie. Peter Lang, 2020.

Langendorf, Ernst: Der Sender der Deutschen Freiheitspartei, in: “Widerstand im Rundfunk” (Das Politische Forum, Hessischer Rundfunk, 1985).

Langendorf, Ernst: Im Gespräch mit Leonhard Reinisch, in “Nachtstudio” (Bayerischer Rundfunk, 1988).

Langendorf, Ernst, and Wulffius, Georg: In München fing’s an. Olzog, Munich, 1985.

Langkau-Alex, Ursula: Deutsche Volksfront 1932-1939. Zwischen Berlin, Paris, Prag und Moskau. Band 2: Geschichte des Ausschusses zur Vorbereitung einer deutschen Volksfront. Akademie Verlag, Berlin, 2005.

Langkau-Alex, Ursula: Deutsche Volksfront 1932-1939. Zwischen Berlin, Paris, Prag und Moskau. Band 3: Dokumente zur Geschichte des Ausschusses zur Vorbereitung einer deutschen Volksfront, Chronik und Verzeichnisse. Akademie Verlag, Berlin, 2005.

Marßolek, Inge; von Saldern, Adelheid (eds.): Zuhören und Gehörtwerden Band 1. Radio im Nationalsozialismus. Zwischen Lenkung und Ablenkung. Tübingen, edition diskord, 1998.

Moß, Christoph: Jakob Altmaier – Ein jüdischer Sozialdemokrat in Deutschland (1889-1963). Böhlau, Cologne, 2003.

Pütter, Conrad: Deutsche Emigranten und britische Propaganda. Zur Tätigkeit deutscher Emigranten bei britischen Geheimsendern. In: Hirschfeld, Gerhard (ed.): Exil in Grossbritannien. Zur Emigration aus dem nationalsozialistischen Deutschland. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart, 1983.

Pütter, Conrad: Rundfunk gegen das Dritte Reich. Deutschsprachige Rundfunkaktivitäten im Exil 1933-1945. Ein Handbuch. Rundfunkstudien, Band 3. ISBN: 9783598104701. K. G. Saur Verlag, 1986.

Pufendorf, Astrid von: Otto Klepper (1888 – 1957) – Deutscher Patriot und Weltbürger. Oldenbourg, Munich, 1997.

Sarkowicz, Hans (ed.): Radio unterm Hakenkreuz. Die Geschichte des Rundfunks in Deutschland. 2 CDs. Production: Hessischer Rundfunk, 2004. Deutsche Grammophon. 06024 9819538 (3). ISBN 3-8291-1448-8.

Schadt, Jörg (ed.): Verfolgung und Widerstand unter dem Nationalsozialismus in Baden. Die Lageberichte der Gestapo und des Generalstaatsanwalts Karlsruhe 1933-1940. Veröffentlichungen des Stadtarchivs Mannheim, Band 3. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart, 1976. ISBN 3-17-001842-6.

Stephan, Frédéric: Die Europavorstellungen im deutschen und französischen Widerstand gegen den Nationalsozialismus 1933/40 bis 1945. Stuttgart, Dissertation, 2002.

Watt, Donald Cameron: The Sender der deutschen Freiheitspartei: A first step in the British radio war against Nazi Germany? In: Intelligence & National Security, vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 621-626, July 1991.

Pressespiegel