Or, what the Maunsell forts had to do with a suitcase murder

by Hans Knot

The Maunsell Forts are armed towers built in the Thames and Mersey estuaries during the Second World War to help defend the United Kingdom. In he mid-1960s one these forts — Knock John — was occupied and claimed as the Principality of Sealand by Roy Bates, who started a short-lived radio station. Writing a book about these forts, Hans Knot encountered the story of a mysterious murder case that was never solved. Here, he tells more about it.

A suitcase murder …Of course, 1965 was no exception. As in every year crime and murder took place in the Netherlands. Still, it was very strange that year to be regularly confronted with reports about the discovery of a suitcase in Amsterdam, filled with human remains, believed to have come from a person of Asian descent. On August 25th an aluminium suitcase was found, in the water at the Jacob van Lennepkade, in which a mutilated body was found from which the legs and hands as well as the head had been removed.

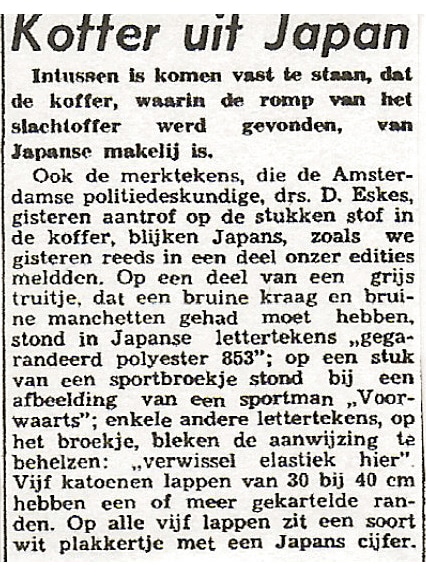

At first it was not understood that this was a corpse of a Japanese person, but all kinds of missing persons were exposed to see if the found ‘body’ belonged to one of them. One of the suspicions was that it was a Frenchman who had abandoned his family and who was known to be somewhere in the Dutch capital. At a certain point, criminal investigation in Amsterdam discovered that the brand of suitcase that had been found was only for sale in the land of the rising sun. The remains of the clothing found were also of Japanese manufacture and some business cards were found.

Precisely these business cards would lead to the name of the person whose remains had been found. It was the 32-year-old Kameda, a representative based in Brussels, for a Parisian trading company, who had her mother’s seat in Osaka, Japan: Nisjizawa Company. It will never be known exactly what happened to Kameda. Four days before the suitcase was found, he had informed his employer that he was going to Africa. However, he told his co-residents of a house in Brussels that he was going to Amsterdam.

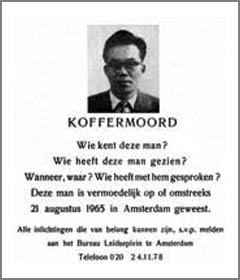

Where he lived in Amsterdam never became known, let alone who killed him. A number of people and friends around Kameda also died. A friend of his would be interrogated in Brussels. The man in question, Okagaki, drove himself to death on the highway. A Japanese journalist, who had had another interview with Kameda on 21th of August 1965, was killed under strange circumstances at the beginning of September that year. At the time, there was widespread speculation that the various victims died in such a short space of time in various parts of the world, all of whom had a line to Kameda, could point to a network of international spies.

A criminal investigation … In the 1980s, I tried to become more aware of the suitcase murder. This as part of my research for a book on the activities of Roy Bates, who owned a former defense tower in the Thames estuary, on which he had founded his own empire, the Principality of Sealand. All practices carried out or not carried out by Roy Bates and his family were highlighted. Including the running of two radio stations at another fort, Knock John, at a time when many offshore radio stations were active off the British coast. During my research for the story, I found out that the Suffolk criminal investigation service had been commissioned by colleagues in Amsterdam to investigate various forts in the Thames estuary. This because there were rumours that remains of the body could be found on one of these forts.

The first time I read about the relation between the suitcase murder and the forts in the Thames estuary was in the magazine 40-45 TOEN en NU while later on I came across a short note in a legal article about the forts. At that time I decided to contact the leader of the investigative team, that had looked into the suitcase murder twenty-two years earlier. So I came into contact with detective Hoegee, who I found willing to talk to me. After this conversation, I made a report for the book, including some important points:

“On Wednesday, August 25th, 1965, 7-year-old schoolboy Joop Braam saw a suitcase floating in the water on the Van Lennepkade in Amsterdam. Joop did not trust the suitcase and warned the owner of a nearby houseboat, who informed the police. Around half past six that afternoon, the Amsterdam municipal police fished the aluminium suitcase, also known as an aircraft suitcase, out of the water and took it with them to the Leidse Plein Bureau for investigation. The officers opened the suitcase in the courtyard and came to a terrible discovery. The suitcase contained the remains or the torso of an Asian person in which several limbs and the head were missing. Research carried out by employees of the Rijswijk Judicial Laboratory, under the supervision of forensic pathology expert Dr. Zeldenrust, showed that the person had been killed about four days earlier.”

And an uncovered identity. My report continued: “A few days after the discovery, it was decided to send found hairs for research to Japan to let scientists there investigate whether these were really hairs from someone of Asian descent. On a part of the left arm, which was still present on the suitcase, Dr. Zeldenrust found small scars that could have come from injections, suspecting that the person later known as Kameda, had been murdered by poisoning. On September 2nd, 1965 the identity of the Japanese person was revealed as being the 31-year-old Kameda. He was last seen in Brussels, where his car with a sum of money was also found during the investigation. Investigation had shown that Kameda should have had at least another twenty-thousand guilders in cash in his possession.”

“Hoegee also told me that information gathered from colleagues in Osaka had revealed that in mid-July Kameda had written another letter to his wife in which he wrote, among other things, that he felt enormously lonely and hoped to be able to return to Japan soon. In the meantime investigations were being carried out in various places in the Netherlands and Belgium into the possible presence of missing body parts. Because a tip had come in that it was quite possible that physical remains might have been hidden on one of the forts in the Thames estuary, some of which were used as a base for a radio station, the colleagues in Suffolk were asked by the Amsterdam criminal investigation department to investigate the aforementioned forts. However, the investigation yielded nothing.”

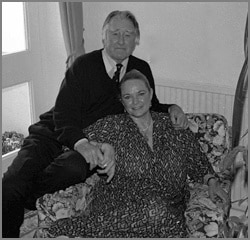

So far my report goes. The remains of the body were eventually cremated in The Hague, after which the urn and its ashes were transported by plane to be buried in Osaka. Detective Hoegee told me in 1987 that the file was closed two years after Kameda’s death without a perpetrator being found. In the spring of 1988, I decided to visit the Bates family, living in White Cliff on Sea, once more to ask questions about some matters that were not yet entirely clear to me regarding all the activities of Bates, his family and associates, as I was finishing my book, later released as The Dream of Sealand (Amsterdam: Stichting Media Communicatie, 1988). One of my questions related to the investigation carried out by the Suffolk Police Investigation Team.

When I spoke to Joan and Roy Bates about the case, they were sitting listening breathlessly and when I asked Roy if he knew about the investigation by the police, he answered very firmly: “This is all completely new to me and I know nothing about this case. It happened during the time that I sailed a lot on one of my fishing vessels. Of course you come into the many little harbours of South East England and I can tell you that the skippers there share everything with each other but I have never heard a word about this investigation. Just assume it’s all nonsense.” Afterwards it appeared, via the file shown in Amsterdam, that there had indeed been an investigation into Knock John, but that Bates preferred not to be reminded of this police investigation at the time.

From: Soundscapes — Journal on Media Culture

volume 21, may 2020