Radio Morue, the offshore radio station for Newfoundland fishermen, operated in the Grand Banks, a cluster of underwater plateaus southeast of Newfoundland on the North American continental shelf, renowned for its turbulent seas. In the depths of 25 to 100 meters, the cold Labrador Current converges with the warm Gulf Stream. The Atlantic waters off Newfoundland were celebrated for their copious cod population, serving as the foundation for stockfish.

Established in the late 1930s, Radio Morue broadcasted programs from the hospital-sailing ship Saint-Yves. The vessel had been equipped by the Société des Œuvres de Mer and navigated the Newfoundland coast to aid French fishermen. This offshore station was initiated and managed by Father Yvon (Yvon de Guengat), a Capuchin priest affectionately known as the “Apostle of the Sea“.

The Société des Œuvres de Mer had the objective of providing “material, medical, moral, and religious support to French and foreign vessels, particularly those engaged in the grande pêche, through the operation of hospital ships.” During that period, the grande pêche (great fishery) referred to cod fishing along the shores of Newfoundland, Iceland, Saint-Pierre and Miquelon, and Greenland. About 300 sailing ships, known as terre-neuvas or terre-neuviers, stationed in continental France or Saint-Pierre and Miquelon, were crewed by more than 10,000 sailors. Father Yvon referred to them as “the convicts of the sea” due to the challenging nature of their maritime existence.

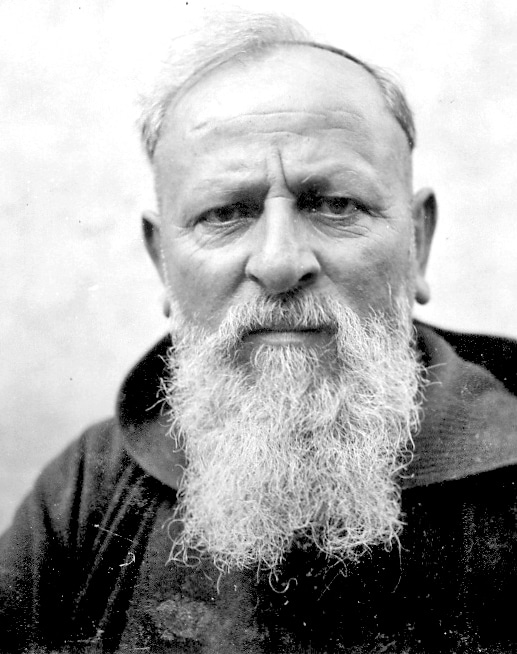

Father Yvon

Father Yvon was the religious name of Jean-Marie Le Quéau, a Capuchin born on November 28, 1888, in Guengat in the Finistère Brittany department.

During World War I, Jean-Marie Le Quéau served as a stretcher-bearer and was wounded, earning recognition for his bravery. He was ordained as a priest in 1921 and initially stationed at a Capuchin monastery in Lorient. Due to his eloquence, he was sent to preach in often quite secularized communities in Brittany, where “he immediately caused a scandal with the militant energy of his sermons.” In 1931, he was appointed as the chaplain for the Newfoundlanders and held this position until 1940.

He then boarded aid ships of the “Société des Œuvres de Mer” (which equipped seven hospital ships successively between 1896 and 1939), especially in the 1930s on the hospital schooner Saint Yves. He served the cod fishermen, took care of the mail, became a radio host on “Radio Morue” on the ship Saint Yves, and made films documenting the harsh life of sailors in the 1930s. During his ten years on the high-sea fishing schooners, he earned the nickname “Le Typhon” and was regarded as the “Abbé Pierre” of the fishermen. He continued to denounce the miserable conditions imposed on sailors by shipowners, coining the term “prisoners of the sea,” as well as the tough life of the young pebbles on the banks of Newfoundland.

“I am the biggest priest in the world. My parish is 1600 kilometers wide and 4,000 kilometers long,” declared Father Yvon in March 1937 to the Havas agency. On his small sail and motorboat, laden with medicines and tobacco, he navigated the Grand Banks in pursuit of Newfoundland fishermen.

“A genuine game of hide and seek,” he remarked. “What do I bring them when I manage to board their sailing ships? First, the mail: in 1936, I distributed 16,437 letters and 2,233 packages. It is impossible to fathom the comfort these packages of sweets and letters from mothers, wives, fiancées, and children bring to the Grand Banks of Newfoundland. And also the solace of religion. There are unfortunate individuals who are sick and despondent, fearing never to see the steeple of Saint-Malo again. I have them brought aboard the ‘Saint-Yves,’ and during the sole campaign of 1936, the accompanying doctor performed 17 operations.

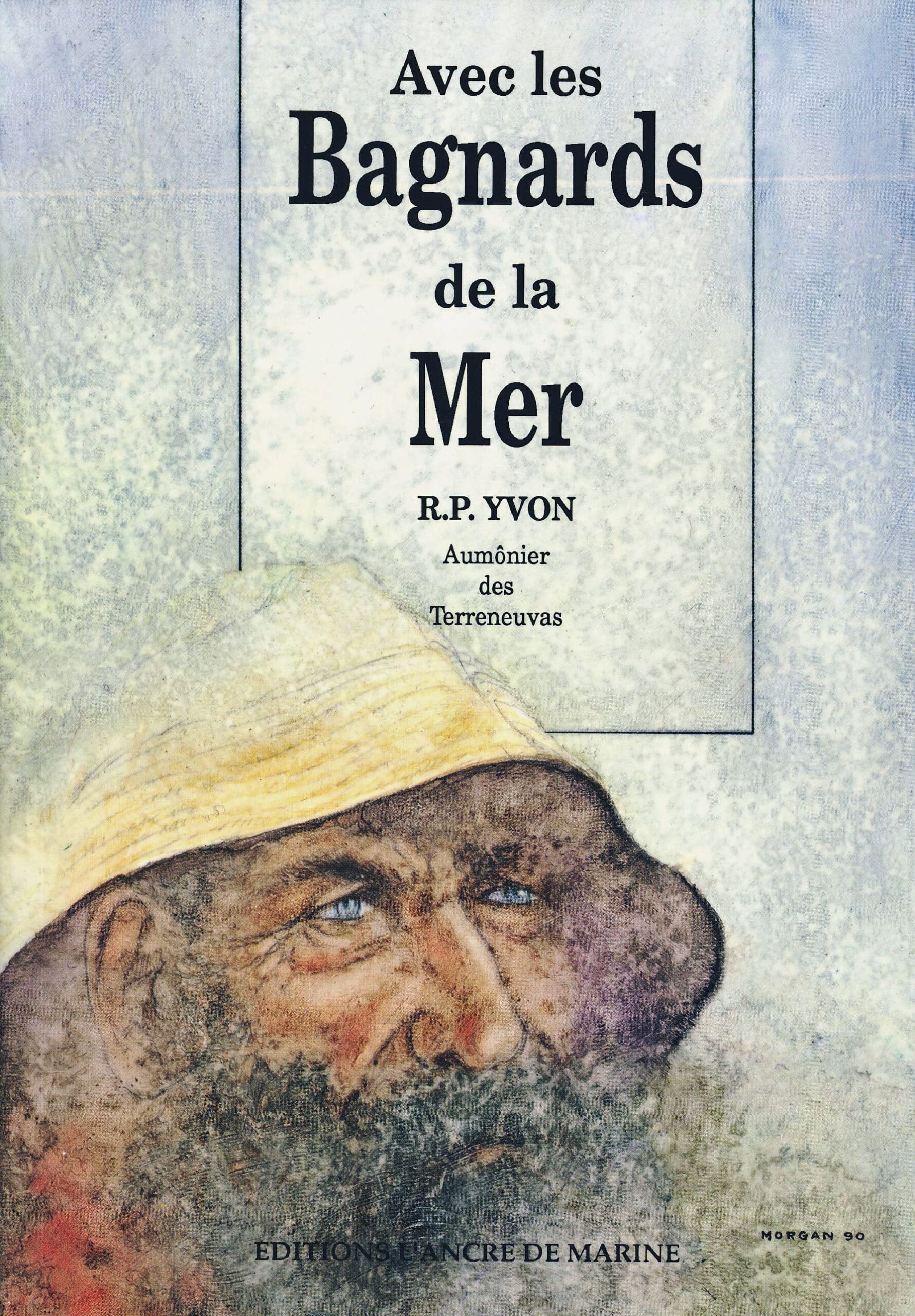

Father Yvon also wrote two books: “Avec les pêcheurs de morue de Terre-Neuve” (1936) and “Avec les bagnards de la mer” (1946).

With his fiery temperament, free spirit, and untamed nature, he did not only make friends. Eventually, his superiors sent him to India. He remained in India until 1948, bringing back ethnographic films, including “À l’assaut de la jungle,” and publishing articles documenting the misery of the subcontinent. Afterward, he retired to the Capuchin monastery in Guingamp in the Côtes-d’Armor department in Brittany, where he passed away on March 13, 1955.

The Saint Yves

Constructed as a two-masted schooner-rigged wooden “dundée” by Chantier Navals de Normandy, Fécamp (Département Seine-Maritime in Normandy ) for the Verdoy family, the vessel was launched on 25th November 1928 under the name Willy Fursy. With a tonnage of 115 tons and dimensions of 27 x 24.90 (bpp) x 7m, and a draft of 3.45m, the ship was completed on 14th February 1929, with Graveline, France as its homeport. On the same day, under the command of skipper Joseph Soonkindt, it set sail from Graveline for the cod fisheries off Iceland until 1932, later continuing its operations on the west coast of Greenland until 1934.

In 1935, the vessel was acquired by La Société “Œuvre de Mer” in Saint Malo and renamed Saint Yves. To convert it into a hospital ship, the ship underwent a refit at its builder’s yard in Fécamp. The crew accommodation was modernized with berths and cupboards, along with upgrades to the galley. The hospital area was separated by a strong bulkhead, featuring two wall-hung wash-basins, linen cupboards, and four berths. Additionally, there was a chapel to starboard, adjacent to the galley bulkhead. A cabin under the companionway, leading to the hospital, accommodated two berths with wash-basins and cupboards for contagious patients. Six mobile berths were also provided. To starboard, a room was reserved for visiting patients, which included the operating table, pharmacy, and more.

In the center, separated from the hospital, was the companionway with gangway controlling the inspection room, a compartment for the post office, and aft, the saloon. The chaplain and doctor’s cabin were on either side, accessible from the saloon. Further aft, separated by a double bulkhead, was the engine room housing an 80 HP Bolinder auxiliary diesel and a diesel generator. The oil tanks with a capacity of 10 tons were placed first, followed by the captain’s cabin, the companionway, and the saloon with four berths. The central heating system maintained a comfortable temperature throughout the ship, with the boiler located in the rear saloon. Under the floors were the coal bunker, freshwater tanks, and the chain locker, with the ship carrying 45 tons of cast iron ballast.

The windlass was powered by the engine, and the interior of the deckhouse featured the galley with a stove and bread oven, a cabin for wireless telegraphy, the companionway, and two toilets. The wheelhouse housed the compass, chart table, and other navigation equipment.

In 1935, during the campaign, the Saint-Yves was commanded by Mr. Gervin, with Mr. Blondel as the engineer and M. Duchâteau as the radio operator. Medical services were provided by Doctor Jousset, assisted by nurse Louis Nédelec. The crew included the mate, boatswain, eight sailors, and a boy. During this campaign, the Saint-Yves contacted 141 ships, hospitalized 19 men for 232 days, gave 90 consultations, collected 22 castaways, and distributed and received 13,801 letters between the banks of Newfoundland and the coasts of Greenland.

The campaigns continued successfully in 1936, 1937, 1938, and 1939. It appears that the Saint Yves remained laid up during the Second World War. After the war, it was bought by the Ouhlen du Diben fishponds, refitted for the transport of crustaceans with a fairly imposing footbridge, and renamed Maryannick. Engaged in the lobster and shellfish trade, the Maryannick regularly traveled to Newlyn in English Cornwall and Ireland to fetch shellfish. When not trading, it was often moored in the Morlaix basin. The exact year of its decommissioning and the final location of its hull are unknown.

Radio Morue

Father Yvon, the chaplain of Newfoundland fishermen, conducted the inaugural tests for this novel radio station in Brittany. On Tuesday, March 30, 1937, the initial broadcasts occurred at 10 a.m. and 4 p.m. on the 190-meter wavelength from the ship docked in the port of Saint-Malo. On Monday, April 5, the hospital ship departed from the privateer city toward Newfoundland, conducting further tests at 9 a.m., 4 p.m., and 9 p.m. During the voyage, broadcasts were made at 10 p.m. on a 175-meter wavelength. The Saint Yves expanded its services beyond merely supplying the fishermen, providing medical care, and delivering mail; it now also disseminated fresh news and entertaining music for the fishermen.

Radio Morue aired twice daily during the eight-month campaign, at 3:30 p.m. and 8 p.m. The program included the exact time, weather reports, news from other radio stations, records, and the position of the sailing ship, which also functioned as a hospital. Monthly, the Saint Yves made stops in Saint-Pierre and Miquelon (a small island group east of the Canadian coast, approximately 25 kilometers south of Newfoundland), taking aboard various newspapers to enrich the programs.

Ultimately, I established the Radio Morue transmitter on the ship, broadcasting news from France to the ships at scheduled times. Local news, personal messages, all while acknowledging the presence of God: for the Newfoundlanders, whether from Normandy or Brittany, possess a religious spirit. They heed the call to faith when delivered by one of their own in their language.”

In Gaston Lebarbe’s book “Ar Soñj. Mémoires d’outre-mer d’un jeune Breton,” a unique depiction of the hospital ship emerges: “Its robust oak hull reminiscent of Concarneau’s tuna boats. Designed for its mission as St. Bernard of the seas, an emergency service for the Grand Banks, its interior features a deck reserved for patients alongside the pharmacy and operating room. Unprecedented hammock-like beds, suspended from the ceiling, automatically compensate for the ship’s heel or roll, reducing discomfort caused by the waves by half. The radio equipment, cutting-edge for its time, served as Father Yvon’s platform to declare, ‘This is Radio Morue!,’ the most unconventional of all radio stations.”

Even the New York Times praised the initiative: “Using the signal “Ici Radio-Morue” (“Here Radio Codfish”) father Yvon, the padre of the codfishermen, keeps in constant invisible touch with his floating parish off the Grand Banks of Newfoundland from his ship Saint-Yves, just off the French coast. From this ship Father Yvon sends his maritime parishioners time signals, weather reports and spiritual aid day after day. On Sundays he broadcasts mass, complete with a gramophone choir. This is followed by folk songs and news from the scattered villages in which the homes of the fishermen lie.“

Father Yvon forged profound connections with the Terre-Neuvas, whether at the House of Œuvres de Mer in Saint-Pierre and Miquelon or aboard the hospital ship. He devoted himself to these men who had ventured far from home to earn their daily bread under extremely challenging conditions.

His greatest fear was the “cruel demon of boredom that sailors call ‘le cafard’.” In the early 1930s, he conceived the idea of a radio program called Radio-Morue.

In his book “Avec les bagnards de la mer” (With the Convicts of the Sea), he recounted the challenges he faced in installing a transmitter on the Saint Yves and battery-powered receivers on fishing vessels. Notably, he received no assistance from ship owners, resistant to any distraction, even a beneficial one, and not even from the Société des Œuvres de Mer, which deemed it too costly.

More than these repeated refusals were required to dissuade this determined Capuchin, nicknamed “the Typhoon”. He cajoled, prayed, and became impassioned to obtain the necessary equipment.

What content did this program have? Excerpt from “Avec les bagnards de la mer”:

“Attention! First, here is the ‘top’ – that is the exact time, if needed for navigation. Then it’s the ‘météo’ that announces the weather and warns against potential challenges.

Then their personal dispatches, to them, the sailors, which once never reached them, as the position of the boats was unknown. Then the ‘Bulletin paroissial’ from their hometown. With his warm and cordial voice, Father Yvon reads, on air, the births from their village… They thus learn, sometimes all at once, that they are the father of twins (…) the festivities, the gatherings… but not the deaths.

Then the news from France. Then the Saint Yves indicates its route so that the sick can be brought to it. Then a word from the chaplain for the spiritual comfort of souls. Father Yvon announces a mass for those lost at sea. There is an average of one per week.”

A bit of music, a few songs, and it’s time to part until tomorrow, same time.

Thus, for 60 minutes, the shores of France drew nearer, loved ones as well, pushing back the ‘cafard’ and its dark thoughts.

From 1937 to 1939, Radio-Morue went on the air every evening at 6 p.m. for an hour-long broadcast. The broadcasts of Radio Morue concluded with the outbreak of war in 1939. The Saint Yves finally returned to Saint-Malo on 26 October 1939.

Martin van der Ven (2024)

Sources:

https://www.radiotsf.fr/radio-morue-la-radio-offshore-qui-sadressait-aux-terre-neuvas/

https://lheuredelest.org/radio-morue-la-radio-des-terre-neuvas/