It was towards the end of July 1970 and the Radio Nordsee International station ship had left the British coast before dropping anchor again in international waters off the Dutch coast near Scheveningen. It was the newspaper ‘Het Parool’ that was the first to report in its evening paper on 28th of July that not only had transmissions resumed off the Dutch coast, but there were also disruptions caused by the broadcasts.

At that time, RNI could be heard on 244 metres, 1230kHz, and on 102 MHz FM. It soon emerged that there was interference in the western coastal areas to the programmes of Hilversum III, which were entering the airwaves via the 240 metres at the time. The aforementioned newspaper reported that it was mainly due to the high power RNI was radiating. ‘Hilversum III, due to international agreements, has a low broadcasting power’. It was also reported that RNI was using a frequency officially allocated to a radio station in Hungary.

The newspaper also reported that the radio and television department of the P.T.T. had now also discovered the interference and it would report its findings to the then Minister of Transport and Public Works as soon as possible, after all, any action against RNI had to be taken from the government side. Another comment from a P.T.T. (responsible for telecommunication) spokesperson added: “It would be a nice opportunity for the government to ratify the Strasbourg Convention against the offshore radio stations.

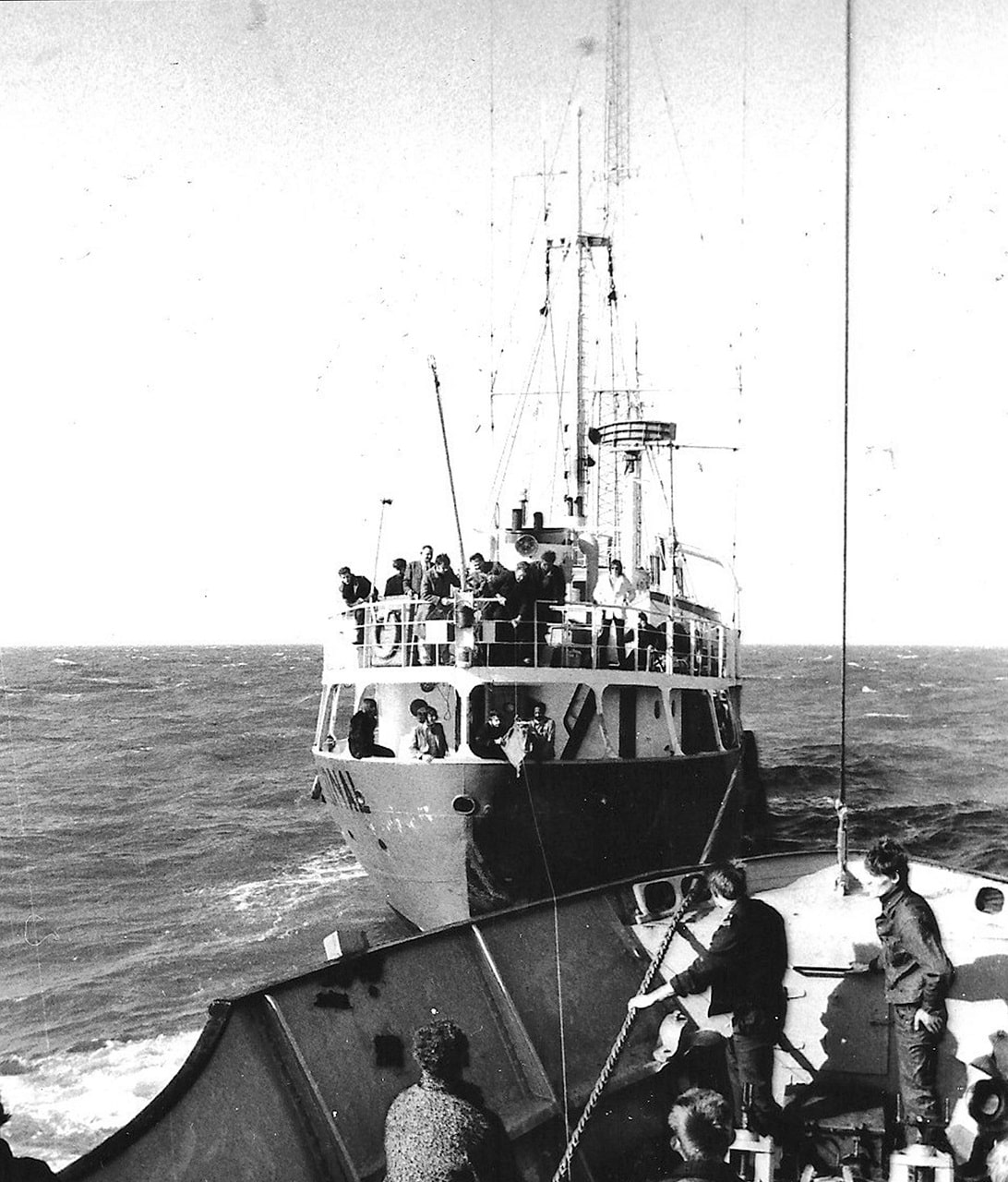

It was also announced in the Parool that the Central Management of the P.T.T. had asked the owners of Radio Nordsee, which was operating from the transmission ship MEBO II, to remove the interference caused on Hilversum III transmissions. This request was made towards the owners, who held offices in Zurich, Switzerland.

One of the Parool journalists also contacted the owners of RNI himself on 28th of July 1970, who claimed to know nothing about the alleged interference: ‘the pirate leaders Erwin Meister (31) and Edwin Bollier (32) are currently staying in the Netherlands. Erwin Meister: ‘Off the British coast we were deliberately disturbed. Now we are off the Dutch coast to avoid this interference and it is not our intention at all to disturb another person. We are not aware that we are disturbing any of your stations. If we receive a complaint about this we will have to switch to another wavelength. The 217, 259 and 270 may also be possible, but as long as we do not know anything officially we will not change anything.”

In the ensuing period, various newspapers wrote about the issue. For instance, the ‘Radio & TV Journaal’ in the Telegraaf on the 30th of July 1970 reported that the P.T.T. sought contact with pirate station’. As an opening, the article started with: ‘What is considered a novelty in Hilversum broadcasting circles’ thereby referring to what was not possible from these circles but did happen by a P.T.T. official, who – falling under the Ministry of Transport and Public Works – had sent a telegram to the owners of RNI.

It added that RNI, disturbed by a British jammer, was forced to move its transmitting ship to international waters off the Dutch coast in order to avoid the influence of this British jammer. And then Henk E Janszen, responsible for the aforementioned column at the time, wrote that although the station had been forced to pop up off Dutch beaches, it subsequently interfered with Hilversum III’s broadcasts.

Big fans of RNI and Veronica probably reacted, whether in thought or not, angrily to the continuation of the article which reported: ‘Hilversum III is Veronica’s counterpart, an undisturbed listening pleasure of light music, cum commercials, is the least that can be expected from the Dutch authorities’.

Quite remarkable since in the following years the editorial staff of the Telegraaf was mainly pro Radio Veronica and not in favour of Hilversum III. Moreover, the term ‘pirate station’ was used again when it came to RNI’s programmes. ‘If Radio Nordsee causes a kink in the cable, it seems logical for the patriotic authorities to do something about it. By analogy with the British authorities also set up a jammer?’

Janszen did conclude that in deploying a jammer, Veronica, a cherished child of countless multitudes of radio fans in the Netherlands, would be compromised. But he also concluded that an official of the P.T.T. – in consultation with colleagues at Verkeer en Waterstaat, took a more friendly route by sending a telegram to the owners of RNI in Zurich, reporting that they were causing interference on a transmitter of the Hilversum broadcasters. No request was actually made to remove this interference, but it had to be clear.

And then all was set because from the broadcasting world in Hilversum, people went on to express an outraged opinion that “such a courteous approach” was, to put it mildly, only going too far. A spokesman for the Ministry of Transport responded laconically to this reaction; “If there is interference then we always take this route. Perhaps the two illegal stations operating off the coast could now be cause for action by draft legislation, based on the Council of Europe Convention that seeks to make the operation of pirate stations impossible.”

On the 30th of July 1970, the Parool carried the disturbing report that Radio Nordsee International’s broadcasts were causing further interference. These included interference to the mobile phone traffic of the bus company West-Nederland N.V. in Boskoop. Meanwhile, the company’s management had filed a complaint with PTT’s mobile phone service. In this case, the interference was caused by interference with RNI’s FM signal.

A PTT spokesman informed the same morning that the interference, caused on Hilversum III’s programmes, had since been removed. The transmitter on board the MEBO II had been changed from 1232 to 1228 kilohertz but it did not mean an end to the interference on the aforementioned mobile phone traffic. A spokesman for the P.T.T. had reported that they would see what measures could be taken to eliminate the interference.

The Parool journalist also got a spokesman for the bus company to speak, revealing that the breakdowns could cause serious safety consequences: for instance, it was not possible to properly hear incoming calls from bus drivers who were more than six kilometres from the depot. This had caused delays during a whole week and created an untenable issue in holiday time. The bus company provided bus traffic on several lines across a large stretch of the west in the regions of The Hague to Utrecht.

According to a spokesman for the bus company, reported in the Volkskrant on the 30th of July, the breakdowns meant that connections were missed and feedback of signals from the buses was completely impossible at one point. Not only was adjustment of frequency promised and implemented by the owners but they also announced that RNI would broadcast programmes only in English and German for the time being and the arrival of Dutch-language programmes, about which several newspapers published a week earlier, would not be initiated. The same day RNI disappeared from the airwaves.

On the 3rd of August, after the necessary technical adjustments had been made on board the MEBO II, RNI could be heard again and either via 1385 kHz or 217-metre medium wave. Also, the shortwave transmitter via 6205 kHz in the 49-metre band was back on air that day. In the dark hours, the medium-wave broadcasts were less listenable due to interference with a Russian radio station.

A day later, on the 4th of August, RNI’s FM transmitter also came back on air and on 96 MHz. Finally, on the 5th of August 1970, the second shortwave transmitter also came on air and could be received on 31 metres, 9940 kHz. On the 23rd of August, RNI disappeared from 217 metres, only to return to the airwaves a day later via 220 metres or 1367 kHz. The decision to start broadcasting via the 220 metres proved to be a successful one without any major problems with interference. More even bigger problems were to follow but that’s for another time.

Hans Knot April 2024